Saudis 'halt' Yemen air campaign with goals unfulfilled

- Published

The Saudi-led coalition declared that its month-long air campaign had been a success

It was not surprising when the Saudis said that they had resumed air strikes against Houthi fighters in Taiz, Yemen's third biggest city.

Negotiations are under way to try to find a way to stop the fighting in Yemen. But the Houthis have fought hard to reach their dominant position in Yemen, and will not give up easily.

On 14 April, the UN Security Council passed a resolution that made clear demands on the Houthis.

Among other things it calls on them to give up their weapons and the territory they have seized, which includes Yemen's capital, Sanaa.

The Saudis say that they are trying to get the Houthis to comply with as much of the resolution as possible.

Political solution

But if and when an agreement is brokered, the chances are that it will be hard to make it stick.

The coalition has warned that it will continue to take action against the Houthis as needed

The Houthis will not return to their home turf in northern Yemen without extracting a price in terms of power and influence.

Even if the Saudis were prepared to agree to that, enforcing a deal in a country as chaotic and ungovernable as Yemen will be a struggle.

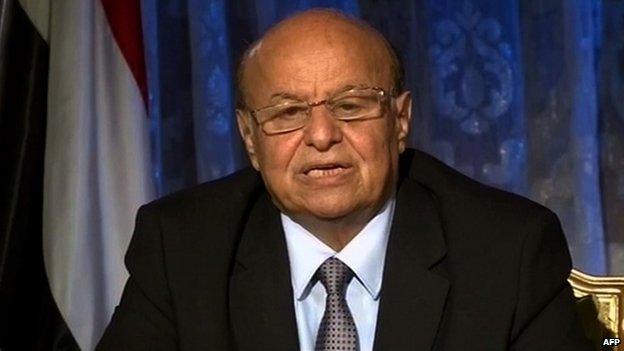

When a month ago the Saudis formed a coalition of other Gulf Arab states, as well as Jordan, Morocco and Sudan, they declared that they wanted to restore to power the internationally-recognised Yemeni president, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi.

He fled Sanaa after the Houthis consolidated their control of the city in January and placed him under house arrest.

The Houthis rejected the UN Security Council resolution, saying it supported Saudi "aggression"

The president then set up an alternative seat of government in the southern port of Aden.

But he had to leave there in a hurry too, as the Houthis advanced on Aden and the Saudis and their coalition allies started their bombing campaign. Now, Mr Hadi is still in Saudi Arabia.

Ex-leader's role

The Saudis say that they stopped their bombing campaign because they had achieved their military objectives, inflicting damage on the Houthis and their allies in the Yemeni army.

In a televised speech from Riyadh on Tuesday, President Hadi promised "victory"

Saudi Arabia's claims that it won the air war will not be credible if it cannot achieve its main political objective of restoring Mr Hadi to power.

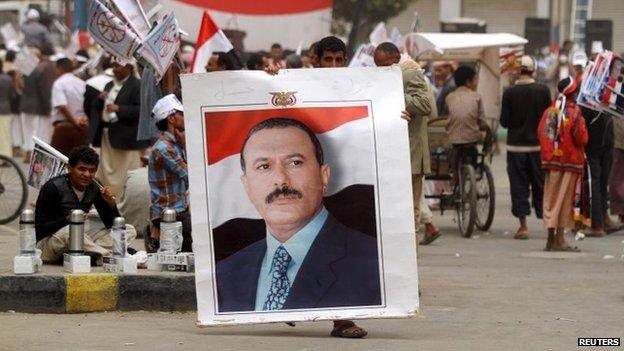

And then there is the question of the former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh.

The Houthi alliance with Mr Saleh, and with the army units loyal to him, was the key to their advance through Yemen.

Mr Saleh led North Yemen from 1978 and became president of all of Yemen after the country was unified in 1990. He kept his job until he was ousted in 2012, but clearly still has a lust for power for himself and his family.

Former leader Ali Abdullah Saleh urged all sides to "return to dialogue"

Saudi sources say that Mr Saleh and his close family will have to leave Yemen as part of an agreement to end the bombing.

But Mr Saleh is at the centre of a network of tribal loyalty and patronage, and has been promoting his son, Ahmed. He will not give up easily either.

Unity in doubt

Yemen is a deeply fractured country. Yemenis often have more loyalty to their tribe than to the idea of a nation state.

Militiamen have vowed to fight the rebels until they are driven out of the South

The most aggressive al-Qaeda franchise in the Middle East is active in its so-called "ungoverned spaces".

Even before the current crisis many Yemenis did not have enough to eat. The capital is running out of water. Now Yemen is gripped by a major humanitarian emergency.

Even though air raids have resumed, the end of the main bombing campaign might allow deliveries of humanitarian aid.

Longer term, the unity of the country is in doubt.

It was divided between North and South until 1990. There is a chance that by design or just through the pressure of events, Yemen could break up again.