Countdown to Iran nuclear deal - but resistance remains

- Published

- comments

The so-called p5+1 and Iran agreed a framework deal this month after marathon talks

A historic deal with Iran over its nuclear programme is now within reach - but it's still uncertain whether this rare chance to resolve a major security challenge of our time through diplomacy will be grasped.

This week, the prospect of a final deal, which must be reached by the end of June, could be pulled in two different directions.

In New York, Iran and world powers are resuming negotiations that, earlier this month, ended with a broad framework of understanding on an accord to curb Iran's ability to produce a nuclear bomb in exchange for relief from crippling sanctions.

In Washington, the US Senate will begin debate on bipartisan legislation to subject any final nuclear accord to review by Congress and a potential vote to approve or reject it.

Republican senators have already filed amendments that the bill's sponsors warn could jeopardise a rare bipartisan measure.

They include a requirement that Iran recognise Israel, link a deal to the release of American citizens detained in Iran, and require any final accord to be given the status of a treaty which would need approval by two thirds of the Senate.

"Never underestimate the ability of Congress to wage political guerrilla warfare to stop the deal," warns Paul Pillar, a former CIA officer who is now a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute.

"The real story now is what the presidents of Iran and the United States do to deal with their own domestic resistance to any rapprochement," he said in a recent seminar on Iran at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

"The main problem is in Washington," he added.

Political discord

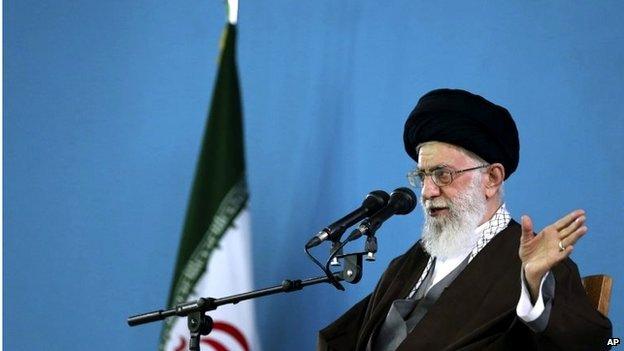

Iranian hardliners have also had harsh words for the US. The country's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei has described the US's intentions as "devilish".

The two sides are meant to reach a comprehensive deal by the end of June

However, Mr Khamenei, whose word carries most weight in the Islamic Republic, also said in a speech broadcast live on state television: "I neither support nor oppose the deal. Everything is in the details."

Negotiators from Iran and the US face political battles to sell the deal at home.

One Western diplomat told me there was an agreement not to criticise each other in public over competing political narratives.

After an outline agreement was agreed in April, political discord erupted immediately over the timing of sanctions relief.

Iranian leaders have declared that restrictions would be lifted as soon as a deal was done.

However, Western diplomats say a phased process of easing sanctions depends on IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) verification that Iran has complied with its obligations under the deal, including a two-thirds reduction in the number of its centrifuges, limits on its uranium stockpile, and what's been described as an unprecedented inspections regime.

"If the Ayatollah's version of the framework is the final deal, there's no way this is getting out of Congress," Republican Senator Lindsey Graham told journalists last week in a briefing in Washington.

But Ali Vaez, senior Iran analyst at the International Crisis Group, insists: "Differences are semantic, they're spin, not substance."

"This is still excruciatingly difficult but, in reality, most of the difficult political decisions have already been taken," he says.

Veto threat

In Vienna last week, negotiating teams met to resolve disagreements and sharpen details on outstanding issues including sanctions, and the future of Iran's research and development programme.

"The pace is slow but it is good," was how Iranian negotiator and deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi described efforts so far to start drafting a final text.

This week Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif is meeting US Secretary of State John Kerry and the EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini in New York on the sidelines of a review of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Iran's final decision with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei

Meanwhile, a chorus of critics across the Middle East is calling for sustained pressure on Tehran to halt its nuclear and political ambitions at a time of rising turmoil in the Middle East.

The most vociferous is Israel, which vows to do everything possible to stop a "very bad deal" which it insists threatens it, and the wider region.

Gulf states including Saudi Arabia are also deeply troubled by this engagement with a rival playing a decisive role in destructive wars in Syria and Iraq, as well as in Yemen.

US President Barack Obama has invited six leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council to Camp David this month to discuss concerns and try to convince them of the wisdom of a deal.

"This deal is the right thing to do for the United States, for our allies in the region, and for world peace regardless of the nature of the Iranian regime," he told National Public Radio in an interview that impressed Iranian commentators with its level of detail on the contours of the final agreement.

Iran's President Hassan Rouhani is also reaching out to world leaders and his domestic opponents to secure a landmark accord that he hopes could help achieve the economic and political reforms he promised Iranians when he was elected.

"We declare to you we are not negotiating with the US, the US Senate, the House of Representatives. The party we are negotiating with is called the P5+1 group," he said.

A highly technical deal on a major security threat is, in this last punishing stretch, profoundly political.

"Wanting a deal so badly is dangerous but not wanting a deal is equally as dangerous" was how Senator Graham described it.

For now at least, there is a sense that forces pulling for a deal are greater than those pushing against it.