Palmyra: IS threat to 'Venice of the Sands'

- Published

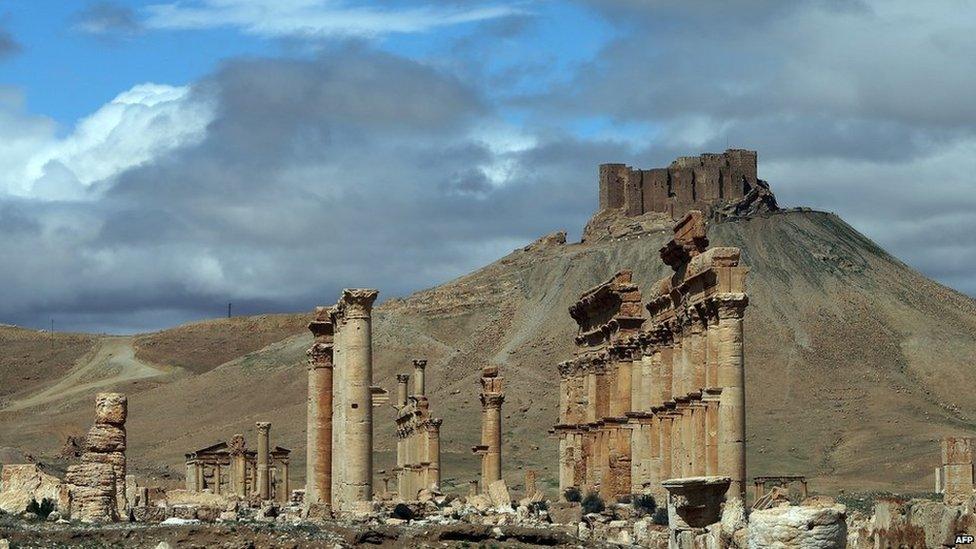

Palmyra is one of the best-known ancient sites in the world

Palmyra is in danger. As Islamic State fighters clash with Syrian government forces around the historic site, it is worth considering what the loss of this wonder, dubbed the "Venice of the Sands", would mean for the world's cultural heritage.

Palmyra is the last place anyone would expect to find a forest of stone columns and arches. Travellers in the 17th and 18th centuries were repeatedly astonished by what they saw: a vast field of ruins in the middle of the Syrian desert, roughly half-way between the Mediterranean coast and the valley of the River Euphrates.

For anyone visiting, however, the key reason for the site's prosperity is immediately apparent: ancient Palmyra sits at the edge of an oasis of date palms and gardens.

It was as a watering place on a trade route from the east that Palmyra's story begins, and the very name Palmyra refers to the date palms that still dominate the area (the origin of its Semitic name, Tadmor, is less certain; a derivation from tamar - date palm - is favoured).

Palmyrene power

For such a remote city Palmyra occupies a prominent place in Middle Eastern history.

From modest beginnings in the 1st Century BC, Palmyra gradually rose to prominence under the aegis of Rome until, during the 3rd Century AD, the city's rulers challenged Roman power and created an empire of their own that stretched from Turkey to Egypt.

Palmyra was once a thriving trade hub to rival any city in the Roman Empire

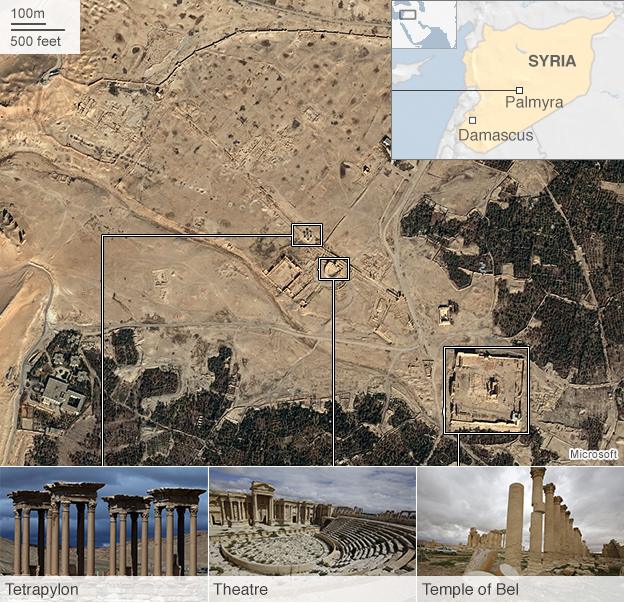

The remains, like the ancient theatre, drew throngs of tourists before the war

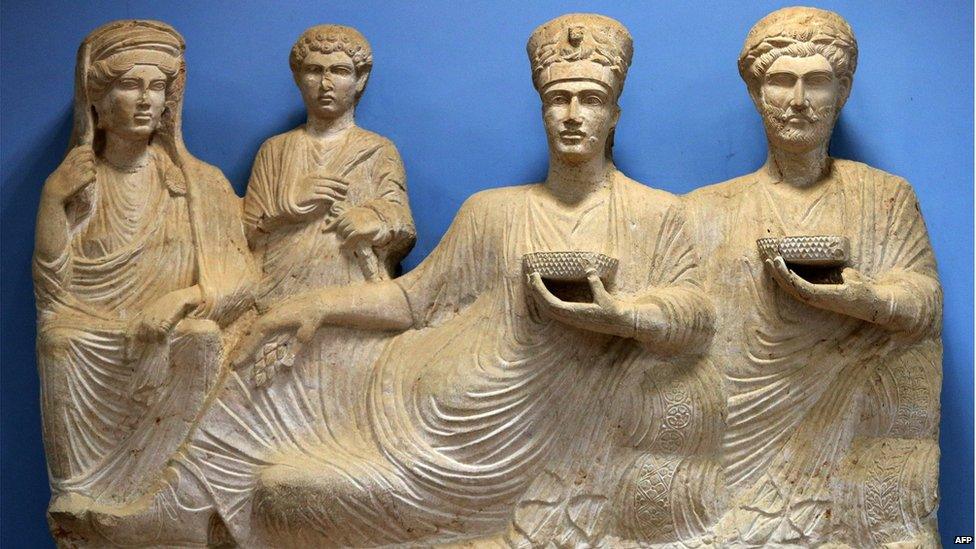

Some of the site's priceless artefacts are kept in Palmyra's archaeological museum

The story of its Queen Zenobia, who fought against the Roman Emperor Aurelian, is well known; but it is less well-known that Palmyra also fought another empire: that of the Sasanian Persians.

In the middle of the third century, when the Sasanians invaded the Roman Empire and captured the Emperor Valerian, it was the Palmyrenes who defeated them and drove them back across the Euphrates.

For several decades Rome had to rely on Palmyrene power to prop up its declining influence in the east.

Unique attributes

Palmyra was a great Middle Eastern achievement, and was unlike any other city of the Roman Empire.

It was quite unique, culturally and artistically. In other cities the landed elites normally controlled affairs, whereas in Palmyra a merchant class dominated the political life, and the Palmyrenes specialised in protecting merchant caravans crossing the desert.

Like Venice, the city formed the hub of a vast trade network, only with the desert as its sea and camels as its ships.

Even so, archaeology has revealed that they were no strangers to the sea itself.

Palmyrenes travelled down the Euphrates to the Gulf to engage in seaborne trade with India, and even maintained a presence in the Red Sea ports of Egypt.

The wealth they derived from the eastern trade in exotic goods they invested in imposing architectural projects in their home city.

The well-preserved remains of edifices such as the great sanctuary of the Palmyrene Gods (generally known as the Temple of Bel), a grand colonnaded street and a theatre stand to this day.

Historical threat

What has been excavated has revealed a vibrant Middle Eastern culture with its own distinct sense of identity.

The Palmyrenes were proud to adorn their buildings with monumental writing in their own Semitic script and language rather than relying exclusively on Greek or Latin (which was the norm elsewhere).

Unesco describes Palmyra as a heritage site of "outstanding universal value"

Palmyra developed its own artistic style, and its own take on Classical architecture. Decorative patterns on its buildings and its inhabitants' styles of dress speak of widespread connections with east and west.

Chinese silks have been found adorning mummies in Palmyrene tombs. Theirs was a cosmopolitan culture with an international outlook.

Yet we still know comparatively little.

Only small parts of the site have been excavated. Most of the archaeology lies just beneath the surface rather than deeply buried, and it is particularly vulnerable to looting.

Like other sites in Syria Palmyra has undoubtedly been plundered during the present conflict. But given the track record of IS in Iraq there are reasons to fear systematic looting and destruction should Palmyra fall into their hands.

If that happens, a major chapter in Middle Eastern history and culture will be yet another casualty of this tragic conflict.

Kevin Butcher is a Professor in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick and a specialist in the Roman Near East. He is author of Roman Syria and the Near East (2003).