Qatar migrant workers describe 'pathetic' conditions

- Published

Working and housing conditions of the 1.5 million migrant workers constructing buildings in Qatar ahead of the 2022 World Cup have been heavily criticised.

The Gulf state has made little progress on improving migrant workers' rights, despite promises to do so, according to the rights group Amnesty International.

Qatar disputes the claims and says improvements have been made.

Here, we speak to three construction workers who have worked on sites in Qatar recently. They describe the conditions there as "pathetic" and "oppressive".

'Frank' (not his real name), 30, from Kenya

"I came to Qatar from Kenya last June to work on the construction sites here.

I got the work through an agency. I was paid $350 (£223) a month when I got here, which was a lot less than I was promised. I also spent a lot to get here - over $1,000.

I worked at sites building government schools near [the capital] Doha from June to November last year. There are a lot of infrastructure projects going on here, alongside the World Cup venues.

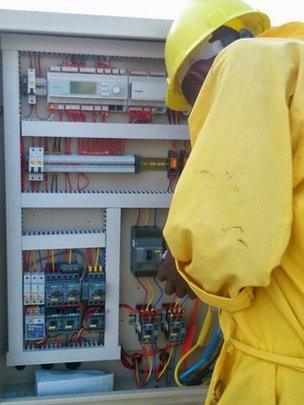

"Frank" sent this picture of the construction site he worked on near Doha

The main site that I worked on was not a good environment. The majority of the workers are uneducated, and the companies take advantage of them, so they cannot negotiate.

They just become helpers and are badly paid. Many just end up accepting it, as they cannot go back to their home countries, because they are supporting their families.

I am sending money back to my family. They are all looking to me, but I can't tell them what it is like here, or they would tell me to come home.

When I arrived, I was told that I would be working as an electrician, even though I am not trained, which is dangerous. I got an electric shock on the site once, but thankfully I was OK.

Conditions on the sites are very bad. You work all day out in the open in extreme heat. You start at 04:00 and work all day. There is no cold drinking water on the site, just hot water. It is very oppressive.

"Frank" working on a site near Doha, Qatar

No-one will listen if you complain. We once went on strike because we weren't paid for a month. We were eventually paid, but the management didn't care about our complaints.

Life in Qatar is very expensive. The accommodation is provided through the company, but food and general living expenses make it hard to save anything. I try to send home what I can.

As for the accommodation, I would describe the conditions as pathetic. In the first place I stayed, Al Khor, there were 10 people to one small room, with five bunk beds and nowhere to put anything. The toilets were outside. It was all very inadequate and uncomfortable.

You also have to hand over your passport on arrival, so you can't leave. You feel trapped, like a prisoner.

Mark Lobel reports: ''Our arrest was dramatic - eight cars drove us off the road''

I am now staying in a place called Industrial - where most of the migrant workers live. The hygiene here is very poor.

There are five to a room, which is a bit better, but it is not hygienic. I now work in a mall in sales after being allowed to leave my job at the construction sites. It is a bit better, but still not great.

Life is very hard here. I would like to see the lives of migrant workers here change. It's just a sacrifice now. There need to be improvements made to safety, salaries and accommodation."

'John' (not his real name), from Ghana

"I am a truck driver working on the site of a new port project near Doha. I came here from Ghana a year and a half ago.

Honestly speaking, we are suffering badly at the hands of our employers, especially in the summer time, as it is now.

It is 40-50C here during the day, but there is no air conditioning in our vehicles, and we are breathing sandy air. At times the dust and sand flows in the air like snow.

There is nobody to fight for us. For almost two months now, my company has refused to pay our salaries. Our company is killing us because they don't want to give us the little reward we deserve.

My salary of $550 a month is very low for a driver like me. We have no days off to rest. This not only applies to me - it is the same with every worker at my company.

I start at 05:00 and work until 19:00, with two hours of transportation to the site and back each day.

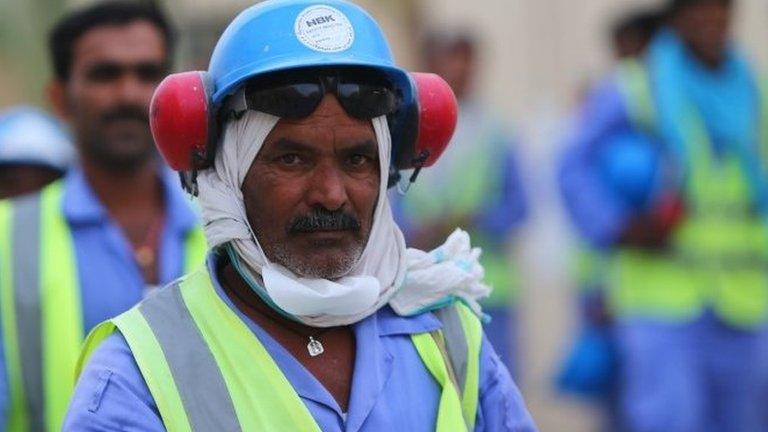

There are an estimated 1.5 million migrant workers currently in Qatar

Qatar has a labour office, but if you report your company, they will definitely send you back to your country. So everyone is too scared to report any problems.

I'm an orphan from a poor home. I couldn't finish my secondary school education.

I have been living in cabins in camps, separated by plywood. Almost all of the workers staying in these camps, are poor and come from countries in Africa and Asia, like Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. We all experience the same problems.

About 15-20% of the workers here have achieved some quality of living standard, with a good salary, due to their educational background, or they have been able to get work through good foreign companies.

But for the rest of us, the payment of salaries is a real headache.

How I wish I could save enough money to leave here to get to Europe or the US.

That's my ambition, because in Ghana, even graduates don't have work, so imagine how hard it is for people like me who had to drop out of school."

Stephen Ellis, from Widnes, UK, worked on a World Cup site in Doha in March

"I worked on one of the World Cup sites in Doha at the end of March. I left after two weeks, because the conditions were an absolute disgrace.

I work as a pipe fitter and supervisor and have been on construction sites all over the world. These were the worst conditions I've ever seen on any site.

Most of the workers at the site where I worked were Indian. They are treated very badly, and the conditions in which they live and work are terrible.

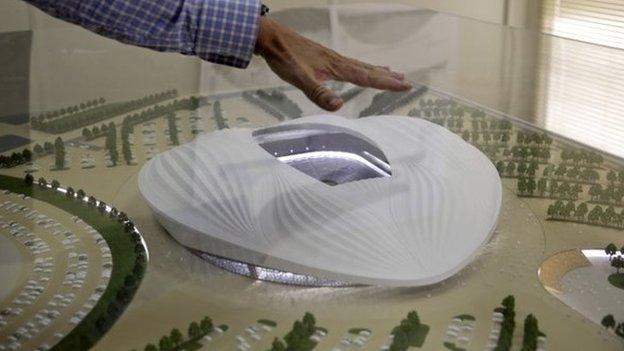

The Qatar Foundation stadium in Doha is one of the venues for the 2022 tournament

There is no drinking water available, there is no air conditioning in their cabins - and this was in 45C heat. They have filthy sanitation, and the food is dished out like in the Oliver Twist movie.

However, what's even worse is the on-site safety, or lack of it. It does not exist, and my friends and I, who went to work there together, were horrified at the risks taken every day on the site.

We were told that before we started there, one Indian worker had been killed.

The site was run totally by Indians, and they were treating their own people very, very badly.

But the upper management did not seem to care. They were just turning a blind all to it all. We were told by English managers that if we didn't like it to leave, so we did.

There were also other Brits, along with myself, who were treated just as badly.

We were paid a lot more than the Indian workers - they were on about $50 a week, and we were on closer to $33 an hour - but we were still ripped off because we left early."

- Published21 May 2015

- Published19 May 2015

- Published18 May 2015

- Published18 May 2015

- Attribution

- Published24 February 2015