Islamic State: How it is run

- Published

How is Islamic State run?

In a ground mission in eastern Syria last weekend, US special forces killed Abu Sayyaf, a man they described as playing a key role in Islamic State's oil and gas operations.

The American commandos were quickly engaged in a firefight, during which Abu Sayyaf was killed. But their original goal was to capture and interrogate him, apparently in an effort to improve their understanding of how IS works.

It raised the question of how much is known about the structure of an organisation that rapidly overran large parts of Syria and Iraq last year, and has been able to hold onto much of that territory despite months of air strikes by a US-led coalition.

On a broad level the shape of Islamic State may seem fairly clear.

Islamic State has seized large swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq

There are conflicting reports about the fate of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

Its stated goal has been to establish a "caliphate" to rule over the entire Muslim world, under a single leader and in line with Islamic law, or Sharia.

Unlike some other insurgent or militant groups, it holds territory that it seeks to govern. It has therefore set up a bureaucratic system that in many aspects mimics that of a modern state.

The leader or "caliph" is Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai, better known as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

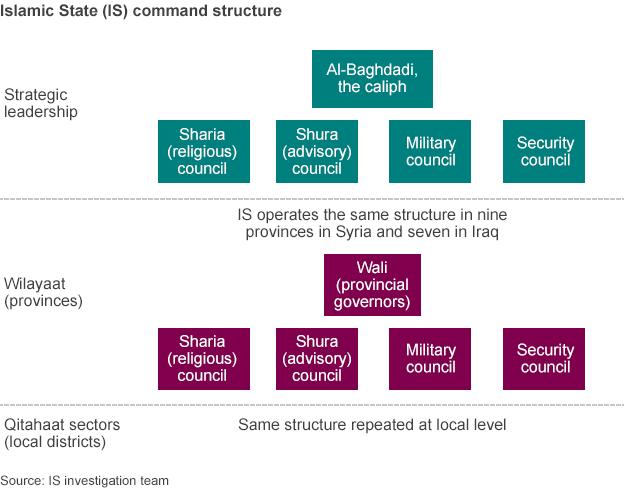

He sits at the top of a structure of advisory councils and administrative departments that are replicated at regional and local levels. These oversee a range of functions and services that include security and intelligence, finance, media, health provision, and family or legal disputes.

IS is believed to operate a "one-plus-four" command structure in Syria and Iraq. From Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi at the top, down to provincial and district levels, IS is headed by a leader and four councils.

The plans for Islamic State's rapid rise were detailed in the papers of Haji Bakr, the man described in a recent report by Germany's Der Spiegel, external as the group's architect.

He laid out a detailed strategy for the takeover and administration of towns that focused heavily on surveillance and espionage, drawing on the experience of a group of Iraqi former intelligence officials.

Haji Bakr was killed in northern Syria in January 2014, several months before his group's sudden expansion.

Yet material on the current structure of IS, and some of the names of the people with positions of responsibility, have also surfaced through administrative documents that have been leaked or seized.

Syrian-born Abu Mohammed al-Adnani is Islamic State's official spokesman

Aymenn al-Tamimi, a fellow at the US based think-tank Middle East Forum, has been building up an archive, external that so far includes more than 120 IS operational documents.

These give directions on everything from strict punishments to child vaccinations, fishing rights, and an order for lorry drivers to give lifts to IS fighters. They are issued for "provinces" as far away as eastern Libya.

"Because there's so much available from these documents we do know a lot more about [IS] than other groups," Mr Tamimi says.

The organisational structure became clearer in June 2014 when the establishment of a caliphate was announced shortly after the capture of the Iraqi city of Mosul, along with much of the north and west of the country.

"The presentation becomes much more formalised and centralised once the caliphate is declared," Mr Tamimi explains.

Islamic State's brutal tactics have sparked fear and outrage across the world

One example is Islamic State's media operation, which is replicated through the various areas under the group's control and appears to be carefully co-ordinated.

After the Nigerian group Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS there was a series of videos from different places of people on the street stating their support for the move. More recently, there was a flurry of videos promoting IS-run hospitals and health services.

Another example was an order issued in December 2014 by the group's general supervisory committee giving operatives across IS-held territory an order to disable GPS devices within one month.

Yet that order was given because of the need for IS fighters to avoid detection as targets for air strikes, and as the campaign against IS has escalated, the group has tried not to give away clues about its operations and the men who run them.

Islamic State's media operation is sophisticated and appears to be carefully co-ordinated

IS talks very little about its leadership, and beyond Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the group's spokesman Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, little is clear about the identity and roles of senior figures.

There were said to be two deputy leaders - Abu Ali al-Anbari in Syria and Abu Muslim al-Turkmani in Iraq.

But last week the Iraqi defence ministry claimed that the group's second-in-command, who they identified as Abdul Rahman Mustafa Mohammed or Abu Alaa al-Afari, had been killed in an air strike.

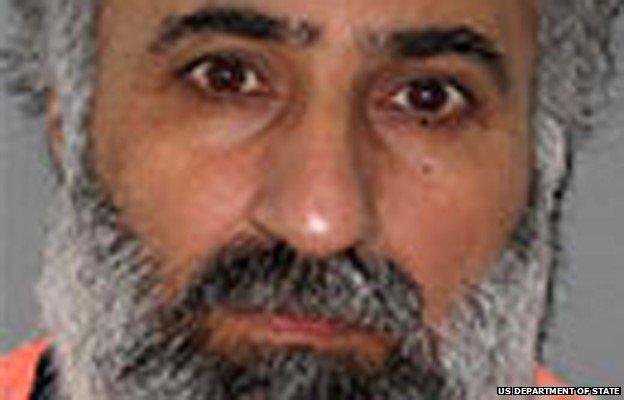

Iraqi sources identified him as the same man that the US had offered a $7m (£4.5m) reward for, a "senior IS official" named as Abdul Rahman Mustafa al-Qaduli, external.

Iraqi sources identified Abdul Rahman al-Qaduli, as Islamic State's second-in-command

There was some suggestion on jihadist social media accounts that Afari and Anbari were the same person, but also scepticism about Iraq's claim.

One problem for those trying to decipher the workings of IS is that there has been relatively little dissent in its ranks, limiting the amount of loose chatter on the internet and the flow of intelligence.

Another is the extensive use of pseudonyms and aliases - the US listed 12 for Qaduli alone. And Der Spiegel's report spoke of a complex parallel command structure staffed by additional commanders and powerbrokers.

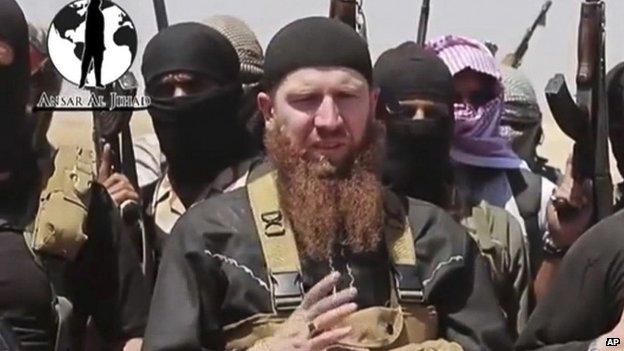

Among the figures that have surfaced in the past are theologian Turki al-Binali, and military commanders Omar Shishani and Shaker Wahib al-Fahdawi.

But there is no consensus on the true extent of their influence, or their formal roles. Some apparently important figures may be given prominence as decoys, fall rapidly out of favour, or be killed.

Tarkhan Batirashvili, also known as Omar Shishani, is a battlefield commander in northern Syria

"The general problem is not knowing who is at the middle or even senior level," says Mr al-Tamimi. "These people are designed to be replaceable."

That may be the case with Abu Sayyaf, who few people appeared to have heard about before the US announced his death on Saturday.

US officials later said his real name was Fathi bin Awn bin Jildi Murad al-Tunisi, though he also had a number of aliases.

Abu Sayyaf's wife, identified as Umm Sayyaf, is now being debriefed in Iraq, where she was brought along with a reportedly large amount of electronic data seized in the raid.

Intelligence officials will be hoping that it sheds valuable light on IS's current decision-making structure and senior operatives.