Jason Rezaian trial: What are Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Courts?

- Published

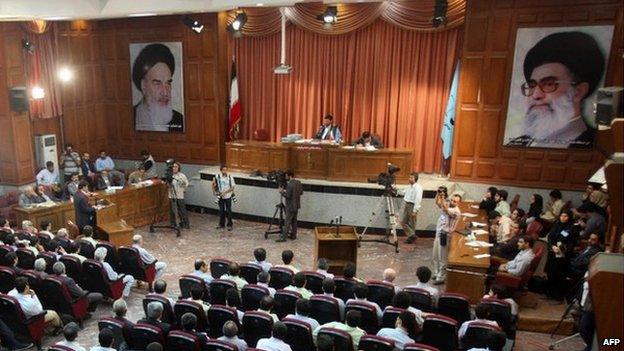

Revolutionary courts were used to try protestors en masse in 2009

The trial of Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian in front of an Islamic Revolutionary Court in Tehran has hardened convictions that his trial will not be fair.

The Islamic Revolutionary Courts in Iran are a legacy of the 1979 revolution, created in the chaos of the turmoil at the time to deliver summary justice to opponents of the Islamic revolution.

According to the UK and Hague-based Iran Tribunal campaign group, in the first decade after the revolution more than 16,000 people were sent to their deaths by these courts.

They remain in force today - 36 years after the revolution despite protestations from critics that their existence is no longer justified.

Islamic Revolutionary Courts are used mainly (but not exclusively) to deal with high-profile political cases. Observers say they are less regulated than ordinary courts, and tend to be more hardline and unpredictable in terms of the judgements they pass.

Human rights organisations have described Iran as one of the world's biggest prison for journalists.

Because of his dual Iranian-US citizenship, Mr Rezaian is of particular interest to the hardliners in Iran. They are opposed to President Hassan Rouhani's relatively moderate policies of opening up to the outside world.

Mr Rezaian may have fallen victim to moves by hardliners to undermine the ongoing talks with foreign powers over Iran's nuclear programme.

Jason Rezaian could face up to 20 years in prison if convicted

No jury

The trial is being held behind closed doors on the orders of the judge, presumably under the pretext that the case involves national security, although this has not been made clear.

"I think the only reason you could possibly imagine that the trial would be closed would be to prevent people from seeing the lack of evidence," Mr Rezaian's brother, Ali, who lives in the US, told reporters. "It's unlike the Iranian court system, Iranian government, to keep things private when they can go out and use propaganda up against people."

Even Mr Rezaian's mother, who has travelled from the US to Tehran for the trial, is not allowed to attend.

In all types of Iranian courts the judge also acts as the prosecutor and is cast by the system as a just figure above human error or bias. There are no juries in Islamic Revolutionary Courts - trial by peers only exists in some special courts, such as press courts which hear cases involving the media.

The judge presiding over Mr Rezaian's case, Abolghassem Salavati, is notorious for passing swift and harsh verdicts against opposition figures.

He is the man who presided over the televised show trials in the aftermath of the controversial 2009 elections which saw hundreds of activists, journalists, lawyers and politicians jailed for supporting reformist candidates.

Many of those on trial made televised confessions - widely believed to be forced - that they were bent on overthrowing the Islamic regime at the behest, or at least incitement, of foreign powers.

Mr Rezaian has been denied a lawyer of his own choosing, in spite of repeated attempts by his family to get the courts to agree.

It is only recently that a court-appointed lawyer has been allowed to see him - and then only for about 90 minutes.

At times the Islamic Revolutionary Courts have refused to allow lawyers with a track record in defending political prisoners to even enter the courtroom.

Today some lawyers are in jail for defending opposition figures.

Judge Abolqasem Salavati is renowned for passing harsh sentences against opposition figures

No evidence

The charges against Mr Rezaian include espionage and propaganda against the government. His appointed lawyer, Leila Ahsan, was informed of the accusations in April - nearly nine months after her client was arrested.

"According to the indictment, he is also facing the charges of collecting confidential information, collaborating with hostile governments, spreading propaganda against the Islamic republic and writing a letter to the US president," she told Tasnim, a hardline Iranian news agency.

No evidence has been presented to Mr Rezaian or his court-appointed lawyer. The date of the trial was only disclosed to him last week. His family have denied the charges, saying he was simply a journalist doing what was expected from him: reporting for his newspaper.

Mr Rezaian's employer, the Washington Post, has tried to send one of its editors to witness the trial. But unsurprisingly, the Iranian authorities have denied the request.

- Published26 May 2015

- Published26 January 2013