Does extremism threaten Hungary's standing in Europe?

- Published

The nationalist Jobbik party has attracted considerable support

European Union leaders face many intractable problems: what to do about Russia, the growing Islamist threat within and beyond its borders, and last but not least the populist backlash shaking the political landscape in a number of countries.

In this last respect, Hungary, and the rise in political extremism there, is a case in point.

Europe has a problem with Hungary, so much so that the European Commission President, Jean-Claude Juncker, was recently overheard, external calling Hungary's leader a "dictator" upon his arrival at an EU summit.

The remark was hastily dismissed as a joke, even though it betrays wider European concerns about an apparent weakening of civil institutions and a backlash against civic groups in the country.

Hungary's Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, is an interesting political case study.

He began as a darling of those on the side of political freedoms, with his strident anti-Communist background.

Yet that all seems a long time ago now.

He hasn't been helped by Hungary's economic problems.

The global economic crisis of 2008 hit Hungary hard, leading to an international bailout.

All this helped Mr Orban sweep to power , externalin 2010.

He has presided over an impressive economic turnaround (of sorts), with measures including taxes on banks and other sectors such as energy.

The public debt is coming down slowly and the economy has returned to growth.

Viktor Orban delights in ruffling feathers

His supporters credit him with leading the country through the crisis.

But foreign investors fight shy of Mr Orban's rhetoric and grandstanding, particularly his skirmishes with big business.

And the public have yet to feel much improvement in their purchasing power - as recent by-election defeats, external for Mr Orban's Fidesz party show.

Unemployment of just over 7% has been exacerbated by a controversial government work scheme, which does little to retrain participants for the market place.

And Hungarians - the young in particular - in search of a better life are still leaving the country in significant numbers.

Since the local elections last October, Mr Orban has seen his popularity plunge and that of the radical nationalist party Jobbik soar.

His response so far has been a series of measures to win back the far-right vote.

Immigration rhetoric

Last month, his government launched an immigration questionnaire asking Hungarians whether they agreed that immigrants endangered their livelihoods and spread terrorism.

"As Brussels has failed to address immigration appropriately, Hungary must follow its own path," Mr Orban insisted.

It is, according to critics, part of an increasingly anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Hungarian government.

Mr Orban has also spoken of the possibility of bringing back the death penalty.

There is no realistic likelihood of this, but Mr Orban glories in saying things guaranteed to irk his liberal critics.

Viktor Orban:

born 31 May 1963 in the small Hungarian village of Alcsutdoboz

trained as a lawyer before entering politics in mid-20s

twice prime minister: 1998-2002 and 2010-present

married with five children

football fan and player (FC Felcsut)

His ruling Fidesz party insists on a version of Hungarian history that stresses Hungary's fate as a victim of World War Two - although government ministers have also acknowledged the country's shared responsibility for the Holocaust.

All this helps garner support in Hungary itself, and not just from those who are attracted to the political extremes.

Many Hungarians approve of Mr Orban's populist and Eurosceptic approach.

They believe Brussels has no real idea of the scale of the challenges facing the country and the institutional and social legacy left behind by decades of political and social neglect under Communist rule.

They argue that one-size-fits-all solutions and liberal orthodoxies are too simplistic and one-dimensional.

And yet, rather paradoxically, overall support for the EU remains strong among Hungarians.

That must be in part due to the financial realities.

Jean-Claude Juncker called Mr Orban a "dictator"

The EU gives more than €5bn (£3.7bn) in financial support to Budapest - some 6% of Hungarian GDP.

But the question for some is what does the EU get in return?

The Orban government, like those of Slovakia and the Czech Republic, is a sharp critic of EU sanctions against Russia over the conflict in Ukraine.

More recently, Hungary's leader attacked fellow EU leaders for what he called their "absurd, bordering on insanity" proposals for migrant quotas.

To his European critics, Mr Orban is a serial offender when it comes to what they call European values, such as respect for human rights.

The row with Europe over the possible return of the death penalty in Hungary is just the latest example. It won't be the last skirmish of its kind.

In the wings lurks the increasingly popular nationalist party, Jobbik, which has openly anti-Semitic supporters.

A Jobbik MP came to wider public attention a little while back for openly spitting on a Budapest Holocaust memorial.

A few years ago, another leading Jobbik figure claimed, during a debate on the Middle East, that people in authority of Jewish ancestry "pose a national security risk".

Government rattled

The party has contributed to a worsening of relations with the Roma, Hungary's biggest ethnic minority community.

The Roma population, which lives on the fringes of Hungarian society, has faced persecution and discrimination for centuries.

Jobbik's success continues to rattle the government of Hungary.

As recently as April, Jobbik won a parliamentary seat previously held by the ruling Fidesz party.

Gabor Vona is trying to rid Jobbik of its extremist reputation

All in all, the political momentum appears to be with Jobbik. And as the party gets stronger and nearer to its ultimate goal of supreme power, it appears to be cleaning up its act.

The party's leader, Gabor Vona, insists he is determined to rid the party of its unsavoury elements and reposition it as a people's party like the German CDU or CSU, in a bid to win outright power in the next general elections, due in 2018.

He has been turning down the volume when it comes to the party rhetoric.

"Whoever has a romantic Nazi yearning... has no place in this party," he declared at a recent political gathering.

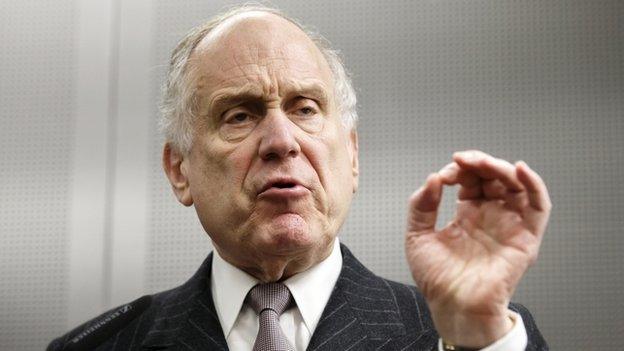

Ronald Lauder has warned of reputational damage

Mr Vona appears to want to shed the party's extremist origins, stay in the EU and work with foreign businesses.

Critics say this is a sham, a cynical ploy to win votes.

In a recent speech in Budapest, the World Jewish Congress leader, Ronald Lauder, said Jobbik's rise was hurting Hungary's image abroad.

His voice matters: Hungary is home to one of Europe's largest Jewish communities, but one recent poll suggested a third of Hungarians expressed anti-Semitic views.

None of this is necessarily helping Hungary's position in the group of EU nations.

Austrian lesson

It is worth remembering what happened when a far-right party entered into a governing coalition in Austria, back in 2000.

The Freedom Party's, external success led the rest of Europe to give Vienna the cold shoulder.

That political reality is probably one of the strongest cards left in the hands of the Hungarian leader.

His combination of nationalist populism and state control of key areas of the economy still rules the roost, for now at least.

- Published24 February 2015