Afghanistan's leaders face battle for peace

- Published

The timing of the attack on the parliament in Kablul was hugely significant

Will there be more and more months of horrific violence in Afghanistan, or will there be historic negotiations?

This year has already seen some of the most important Taliban gains on the battlefield, and the most significant period of informal talks.

Some dared to hope this would be the year when formal discussions between the Taliban and the government stood their best chance of inching forward, after years of a stubborn stalemate and searing attacks.

But this week's audacious attack on parliament has again shredded a slim thread of hope.

The timing magnified the symbolism of this moment - Afghan MPs had gathered, in the holy month of Ramadan, to finally confirm the appointment of a new defence minister, when the assembly was shattered by explosions.

In a tragic coincidence, the official set to take on the top defence job is Massoom Stanekzai, the man once tasked with finding a way forward in peace talks. He survived the suicide attack in 2011 which killed former President Burhanuddin Rabbani.

The Taliban envoy who had travelled to a Kabul house that fateful night, ostensibly to discuss peace, carried a more deadly message inside his turban.

This dangerous business of distinguishing friend from foe is getting harder. So is the challenge of discerning Taliban approaches to end this protracted conflict.

"This attack means that with one hand they are shaking hands like a brother but it means we believe that, not them," a palpably shocked MP Shukria Barakzai reflected to the BBC. "I feel sorry, I really feel sorry."

How the attack on the Afghan parliament in Kabul unfolded

Only weeks ago, she had taken part in an unprecedented meeting in Oslo between an all-female Afghan delegation and representatives from the Taliban political office in Qatar.

Only last week, several Taliban representatives were in Norway again to take part in the annual Mediators' Forum. The discreet gathering, set in a stately manor in quiet woods, was also attended by senior members of the Afghan government and civil society.

The forum began with Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos candidly sharing his experiences of his peace talks with the Farc rebel group, aimed at ending a punishing 50 year war.

But, in his opening public remarks, President Santos made it clear this was "a battle for peace", only waged after he first ensured "military forces were in our favour". While his officials talk, his soldiers fight; there is no ceasefire.

Afghans sitting in the front row listened carefully, and took extensive notes on a conflict which has often been seen as having parallels with their own.

Cups of tea

This year in Afghanistan, the traditional "fighting season," after winter snows melt, is especially intense, and significant.

The attack on parliament, which took the lives of a woman and child and injured dozens more, came in the wake of important news from other battlefields. This year, the Taliban are advancing on some key fronts including Kunduz province in the north, and Helmand province in the south.

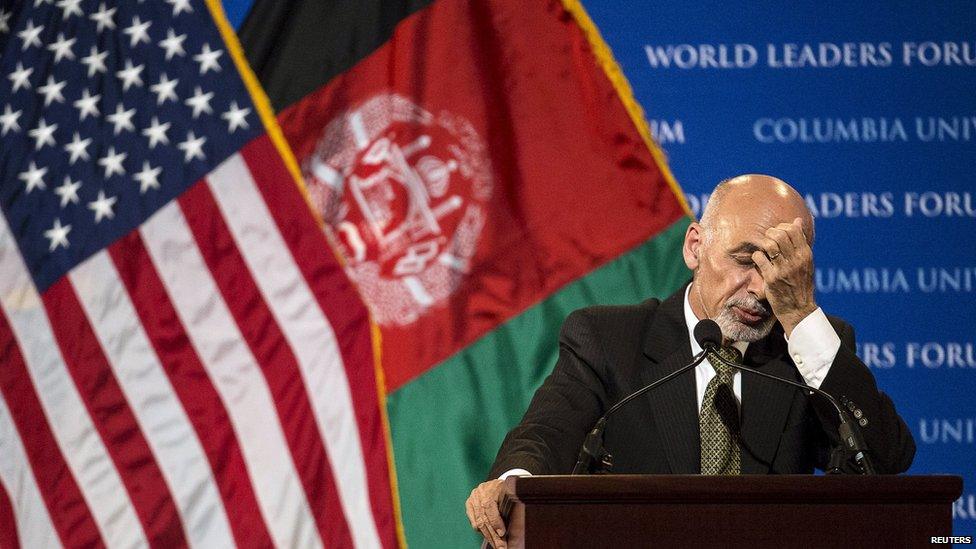

Afghan leaders attended a peace forum in Oslo to discuss ways to end conflicts

Representatives of the Taliban also attended the event and held informal talks on how to improve women's rights

And, yet, there's been much more talking this year too. Over the past six months, Taliban representatives have sat down in Qatar, Dubai, Oslo, and in Chinese cities with Afghan government officials, Afghan women, Western diplomats and aid officials.

Afghan and Western sources, including Taliban, all tell a similar story. In recent months, they've shared cups of tea and proper meals. They've argued over the past, and presented detailed papers on the future.

There's even been the traditional greetings and embraces between Afghan men. We've seen Taliban efforts to reach out to women with new approaches, described as being within Islamic law, on women's rights to work, to be educated and to participate in politics.

"They seem to be trying to change their image," assesses an Afghan woman's activist with knowledge of the discussions. "They're trying to convey a message that they're ready to govern."

What next?

But a critical step in this process is still missing. "The talks of the last six months would have been very significant but every round is the same unofficial dialogue," remarks one Western diplomat working in the region. "What's needed now is the next step."

The "next step" would be face to face formal talks between authorised representatives of both sides.

For all the talking, there have still been no formal talks. There's no Taliban policy that they are ready to negotiate with a government they recognise as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Taliban delegates no longer use the term "puppet government" as much as when President Karzai was in power.

But their official position is still that they will only negotiate with the United States on issues that matter: the presence of foreign troops; the release of their prisoners; the removal of individuals from sanctions lists.

When a flurry of news reports emerged last week that there would be talks at the Mediators' Forum, their website, The Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan issued a statement saying this "claim is untrue and neither is this conference being held for such a purpose".

Even if the Taliban wanted to move to the next step, what would be the process of reaching it?

This is a movement said to rest on allegiances to their Emir, Mullah Omar. But he's not been seen in public since 2001 and there's a growing swirl of speculation over his absence.

Years ago, the political office in Qatar, headed by his former personal secretary Syed Tayyab Agha, was said to have received his blessing to negotiate, but only with US diplomats. Since then, the villa housing the political office of The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan was shut after President Hamid Karzai's vehement protests.

President Ghani has so far failed to secure credible peace talks with the Taliban

President Ashraf Ghani told me months ago that he started working on Taliban talks as soon as he took office last year. His radically different approach to his predecessor rests on working closely with Pakistan which, sources say, has different ideas on which Taliban should sit at any negotiating table.

So far, Pakistan's military and intelligence services, known to have longstanding contacts with Afghan Taliban commanders, have yet to deliver any credible negotiators, or a convincing new process.

"It's reaching the point where Kabul will have to say this new policy with Pakistan is not working," said one Afghan official who had been involved in previous efforts to work with Pakistan in President Karzai's time in office.

The accelerated pace of informal talks and intense fighting also comes at a critical moment for both the Taliban movement and the Afghan government.

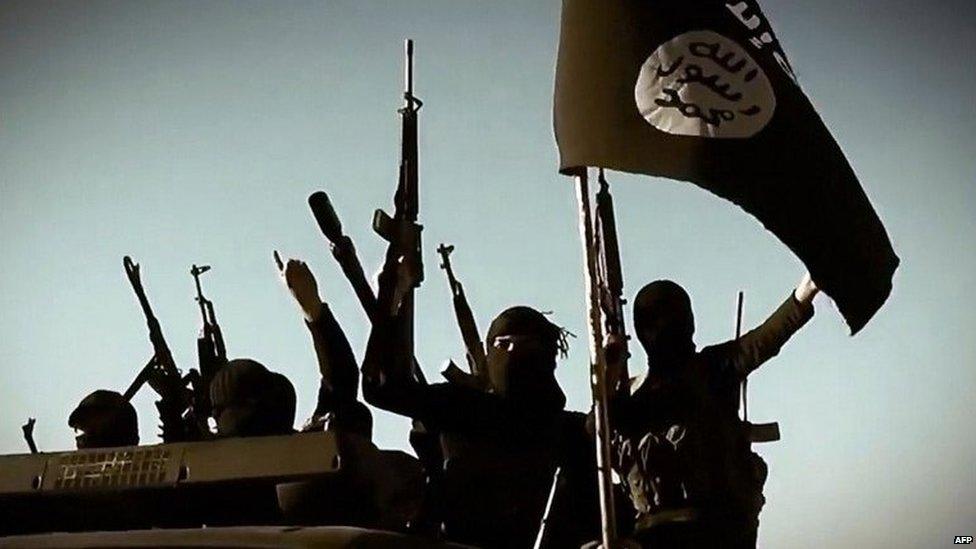

The Taliban are facing a new challenge from a small but increasingly significant presence of fighters declaring allegiance to Islamic State.

Some Taliban fighters previously told the BBC of their intentions to join Islamic State

Its own movement is still deeply divided between senior commanders ready to talk, and those bent on battling to the end. But that hasn't stopped an upsurge in fighting.

"They're throwing a lot into the battle this year including foreign fighters who recently fled the tribal areas of Pakistan," said one aid official in Kabul. "Many Taliban commanders believe it's only a matter of time before the government in Kabul collapses."

In Kabul, a "National Unity" government, combining the political forces of President Ghani and Chief Executive Officer, Dr Abdullah Abdullah, is still struggling to forge a cohesive and constructive working relationship 10 months after it took power.

Last week, at the Mediator's Forum, Afghans heard a Colombian president speak of peace talks as his most important mission in a violent year that, he believes, could still be the most significant in Colombia's embattled history.

Afghans no longer announce that any year is "critical". Every year is. But halfway through this one, no-one can be sure that "a battle for peace" will prevail.