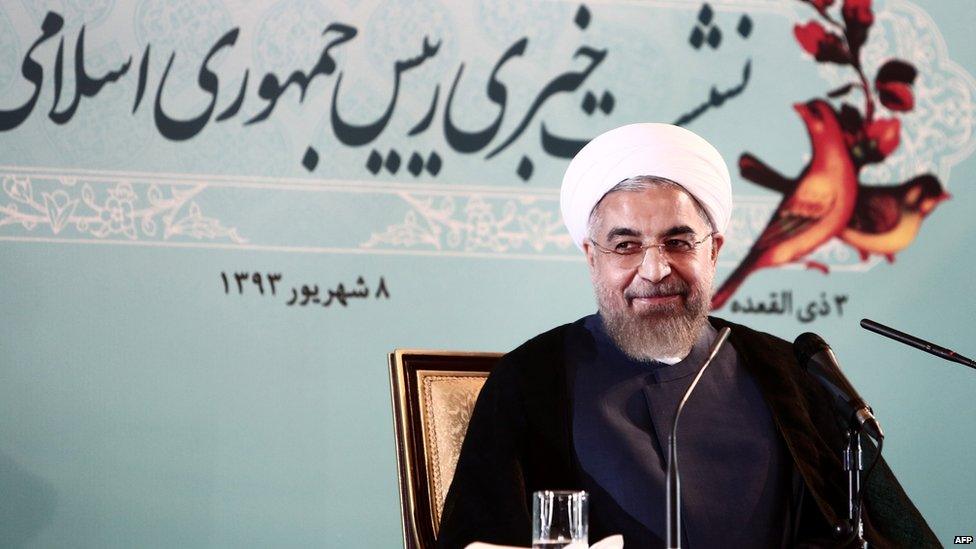

Will Iran nuclear deal be Hassan Rouhani's legacy?

- Published

President Hassan Rouhani promised Iranians he would get sanctions lifted

As international talks over Iran's nuclear programme come down to the wire, the success or failure to strike a deal could be make or break for President Hassan Rouhani.

After his election in 2013, the new president - seen as a moderate abroad - promised to work to lift years of sanctions which have crippled the economy and made life ever-harder for average Iranians.

Iranian hardliners have opposed concessions and compromise over Iran's "national right" to nuclear energy, but the balance so far appears to be heavily in favour of President Rouhani and his team of negotiators.

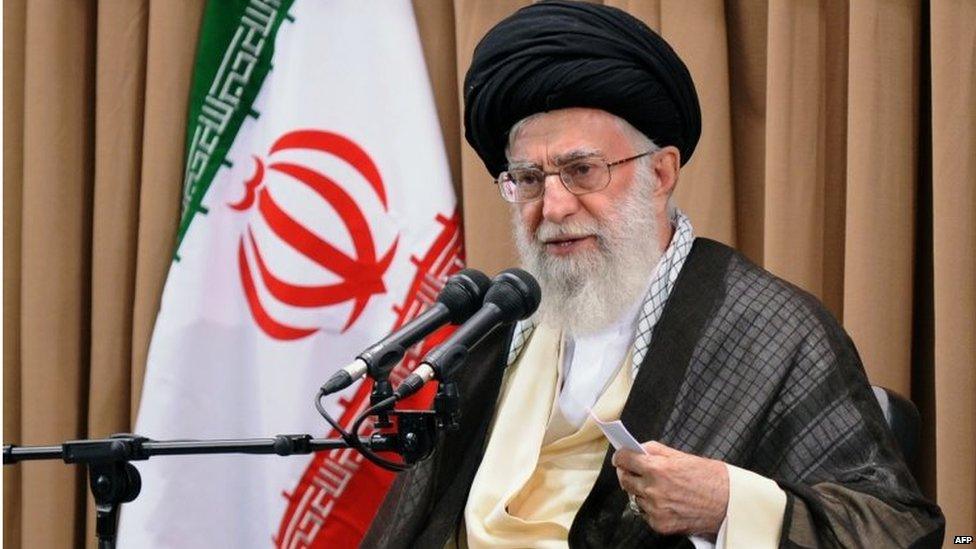

In the end, the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has the final say.

He has publicly backed the negotiating team and in recent days provided them with more flexibility over some aspects of the negotiation while at the same time hardening his stance towards the West.

Views from inside Tehran

All UN and US "economic, financial and banking" sanctions must be lifted "immediately" a deal is signed - and the remaining sanctions lifted "within reasonable time intervals", Ayatollah Khamenei said in a speech, external on Tuesday. He made no mention of EU sanctions.

The hardliners have been at pains for more than a year-and-a-half to refrain from any public criticism of the government while the nuclear talks were in progress.

The instructions to desist came from the Supreme Leader himself, who has called on all officials to ensure a united front was conveyed until the 30 June deadline.

Double-edged remarks from Ayatollah Khamenei, such as "I am neither for nor against the deal", have kept both the pro- and anti-camp in Iran satisfied.

The Supreme Leader has juxtaposed his position in several speeches, not only to survive a possible negative outcome but also to ensure he does not antagonise the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp (IRGC).

The IRGC has never been too convinced by the talks, except for the obvious benefits of lifting sanctions which have affected its multi-billion dollar business empire, though it has given the negotiators its cautious backing.

Parliamentary intrigue

Over the past few months there have been intensive debates inside the conservative-dominated parliament between the two camps.

Iran's powerful Revolutionary Guards Corps has given cautious backing to the talks

Most of the heated discussions have been behind closed doors, but some of it has slipped out, external on social media and the wider press.

"The closer we get to the signing of the deal," said reformist Sharq newspaper on Monday, "the bigger becomes the wave of attacks, and insults on the government of Hassan Rouhani."

Another article blamed former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's camp for "scheming for months" to ruin the prospects of success in the deal for Iran.

The main voice of opposition in parliament is the faction that supports Mr Ahmadinejad, Mr Rouhani's predecessor.

In moves not dissimilar to the Republicans in the US Senate, the faction known as Paidary (persistence) Front, has tabled several motions to try to give parliament the power to challenge a final deal.

None has been successful, and its latest bill was amended in such a way as to take away the power of veto from parliament and put it in the hands of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), the top decision-making body in Iran and loyal to the Supreme Leader.

It is chaired by President Rouhani and includes parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani and his brother Sadeq Larijani, who heads the judiciary.

Its members are mainly hand-picked by Ayatollah Khamenei and also include the chiefs of the army and the IRGC, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and a handful of other ministers.

That is why despite the verbal battles over the past few months, once the deal is sealed by the Supreme Leader there is little anyone can do to oppose it.

Risk of failure

The room for Iran's nuclear team to manoeuvre is limited. The oversight by SNSC would ensure that all requirements laid down by the Supreme Leader and the IRGC are met.

Ayatollah Khamenei has made it clear he will not accept any inspection of military sites (a key demand of the so-called P5+1 interlocutors), backing the requirement laid out by the IRGC.

Ayatollah Khamenei will have the final say over whether to accept or reject a nuclear deal

Despite the red lines, President Rouhani and his negotiators are protected by the Supreme Leader's endorsement.

The danger, however, would be if the deal failed or faced serious obstacles after the 30 June deadline.

In that case, although Ayatollah Khamenei may continue to call for calm, the IRGC, and the conservatives, angered at the failure to lift sanctions, would push the Supreme Leader to take a harder line, switching their substantive majority in parliament against the president, making it difficult for him to increase the reformist share of seats in the next parliamentary election due in February.

The president may continue to wield support from the public at large, but the machinations of those dominant groups are likely to make his position untenable for the next presidential elections due in June 2017.

It is with a view of those elections that not only the president but also all parliamentary factions are leaving themselves room for jockeying.

Dr Massoumeh Torfeh is a research associate at the London School of Economics (LSE) and School of Oriental and African Studies (Soas), specialising in the politics of Iran, Afghanistan and central Asia. Formerly she was the UN director of strategic communications in Afghanistan.