Will Congress scupper US nuclear deal with Iran?

- Published

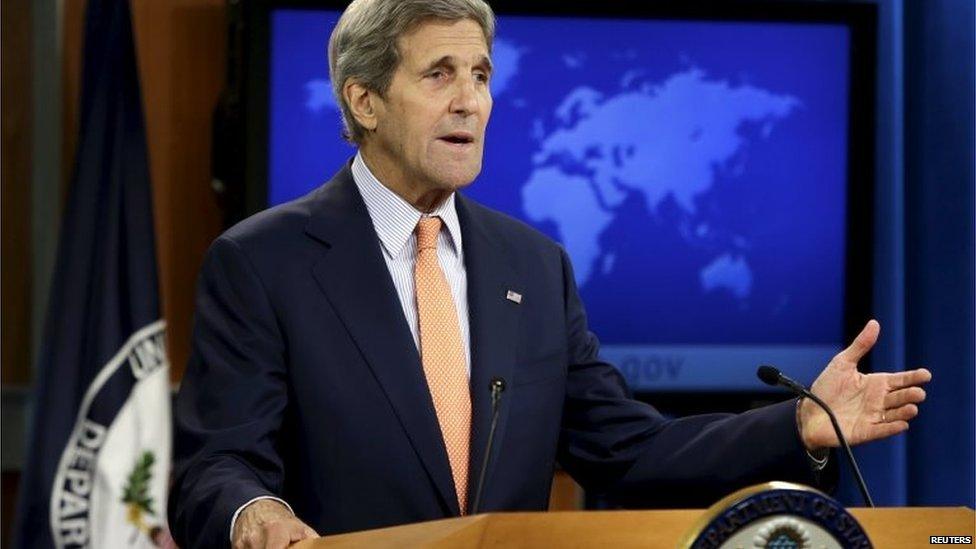

John Kerry has led the marathon talks for the US in Vienna - but a deal will still need the backing of a sceptical Congress

As crunch time nears for an Iran nuclear deal, Washington heavyweights are piling on the pressure.

Bob Corker, the Republican Senator who has led the charge for Congressional oversight, has written to the president, warning against the erosion of red lines.

Five of Barack Obama's top former Iran advisors have signed an open letter expressing concern that the deal might lack sufficient safeguards to deter Iran from building a nuclear bomb.

And the administration has intensified briefings with lawmakers amid a series of media leaks suggesting concessions in the negotiations.

These interventions add to the challenge of the end game, and raise questions about the sustainability and credibility of whatever it might produce.

Partisan politics

Much of the ongoing opposition on Capitol Hill is about support for Israel, whose Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in effect appealed to Congress to block a deal.

And much of it is about partisan Republican politics targeting the foreign policy of a Democratic president.

But Democrats also share some Republican concerns about the negotiations and whether a viable deal is possible with an old enemy still deeply distrusted.

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu warned against a 'bad deal' in a controversial speech to both Houses, much to Obama's chagrin

Several felt strongly that Congress had an institutional responsibility to weigh in on such an important agreement.

The president felt very differently, but he backed down in the face of rare bipartisan support for legislation giving Congress that right of review.

Lawmakers now have 30 days to examine any deal during which time Mr Obama could not suspend US sanctions. And they have the option of rejecting it, although he would veto that.

Common wisdom in Washington says Congress would not be able muster enough votes to block the agreement by overriding a veto.

That calculation is based partly on a letter expressing strong support for the talks signed by 150 House Democrats two months ago.

But in the run-up to the deadline, mounting concern about possible US concessions has created a climate of uncertainty.

Red lines 'crossed'

There is unease about the formula which sharply curbs Iran's nuclear activity but leaves the infrastructure intact.

The restrictions end after 10 years although the verification regime does not.

"We're now managing their proliferation," rather than dismantling their enrichment programme, Senator Corker told the BBC, reflecting a view that President Obama has crossed some red lines since he embraced diplomacy with Iran.

Critics in Congress say Iran must answer questions about suspected past military dimensions to its nuclear programme as part of any deal

Tough inspections "anytime, anywhere" are a red line for Congress, he said, including of military sites, which the Iranian leadership has publicly refused.

He also stressed that Iran must reveal the past military dimensions of its nuclear programme to help guard against such activity in the future.

He was responding to recent suggestions by the Secretary of State John Kerry that Tehran would not be pressed on this point.

Senator Corker said his intervention aimed to "stiffen the spine" of negotiations, not scuttle them.

The statement released by a bipartisan group of arms experts and former senior officials also urged the White House to negotiate a stronger deal.

"This is not roll back of sanctions for roll back of nuclear infrastructure, it's roll back for transparency," said Dennis Ross, one of President Obama's former Iran advisors who signed the open letter.

"If the transparency element of the understandings turns out to be less far reaching, if it looks like roll back for partial transparency, then it becomes more questionable whether Congress could block it. But I think the administration understands that as well as anybody."

Risk of failure

Administration officials have pushed back against media reports that they are softening their position. They insist negotiators are holding the line, and conduct briefings on the Hill several times a week to spell out the details.

"They need to regain control of the message," said one observer.

Whatever the concerns and criticisms, lawmakers are aware that polls show public support for a proposed deal with Iran.

Obama has the power to override Congressional rejection of a deal

And many fear the risks of walking away from the table - which would free Iran to return to large-scale nuclear activity - especially if the US were seen as responsible for sinking an agreement.

"If the United States were to abandon negotiations or cause their collapse, not only would we fail to peacefully prevent a nuclear armed Iran, we would make that outcome more likely," the House Democrats wrote in their letter

But even if President Obama prevents Congress from blocking a final agreement, attempts to do so could still cause Iran and the rest of the world to question America's commitment.

And if he wins because of support from a very small margin of lawmakers, the opposition could continue trying to defeat the deal.

It may have many opportunities if the Iranians are not seen to be meeting their commitments.

Either way, as the presidential election campaign gathers pace the issue is likely to become more partisan, not less.

So if President Obama is able to seal a hard-won deal in Vienna, he may have to work just as hard to sustain it at home.