Can powers meet the 'real' deadline on Iran's nuclear programme?

- Published

US Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif have led the marathon talks

Will Vienna be the venue for the end of a 12-year standoff over Iran's nuclear programme?

"We're not there yet," cautions a Western official, as talks continue into the first week of July and past a self-imposed deadline of 30 June.

"We've reached the point where ministers have to sit around a table and take some decisions," says another.

Most foreign ministers of the six world powers in what's known as the P5+1 group are back in Vienna today.

"The process has moved from the level of experts to ministers, who must now decide on mutually agreed language in the bracketed parts of the document," says Reza Marashi, research director of the National Iranian American Council (NIAC), describing what could be the final phase of the years-long negotiations.

"It's the beginning of the last push."

'Within reach'

Pundits and press are gathered in the Viennese hotel lobby, adjacent to the Palais Cobourg where talks are taking place.

"There's a real sense now that this has to be done," says an observer here who has spent time with the Iranian and American negotiators.

Iran wants to have crippling economic sanctions lifted as quickly as possible

And yet, there's still a possibility that one side or the other could walk away, or one issue or another could still hold up a final deal.

The opportunity to halt Iran's sensitive nuclear work for at least a decade and finally lift the punishing sanctions on the country could still slip away.

"Yes a deal is within reach, but its been within reach for a while," a Western negotiator tells me.

Officials involved in these marathon talks on one of the key security challenges of our time emphasise the extraordinary complexity of what's said to be a 60 page document with numerous annexes that must meet technical and political needs of all sides. Its both highly scientific and deeply sensitive.

The Vienna talks build on a framework agreement reached in early April in the Swiss city of Lausanne, where negotiations lasted late into the night. As significant as the framework deal was, it was still only a broad outline that left some areas still open to interpretation.

'Bullet-proof deal'

In what could be a last push in the coming days, a tangled history of mistrust and misunderstanding still casts a cloud. Its not just about making a deal, but making sure commitments will be kept.

"The deal must be air tight, water tight and bullet proof," says Ali Vaez, a senior Iran analyst at the International Crisis Group who has followed the process from the start.

Issues like reciprocity, sequencing, and most of all verification are under intense scrutiny as the process moves closer to a final hour. A deal would be celebrated by supporters of the process and condemned by hardline critics in many countries including the United States, Iran, the Gulf states and Israel.

Iran insists its nuclear programme is for purely peaceful purposes

Just hours after the deadline was extended for another week, US President Barack Obama gave an indication of what was required to seal the deal.

"If we can't provide assurances that the pathways for Iran obtaining a nuclear weapon are closed and if we can't verify that, if the inspections and verification regime is inadequate then we're not going to get a deal," Mr Obama said.

The president made it clear he was ready to walk away from the talks if it was "a bad deal".

There was also a warning from Iran's President Hassan Rouhani, who spoke of a forceful return to a "previous path" if a nuclear agreement is reached and then violated, sooner than "the other side could even imagine".

Military dimension

As another deadline looms, the softly spoken head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Yukiya Amano, slipped into his waiting limousine outside the Palais Coburg on Tuesday and headed to Tehran.

Mr Amano will take part in talks widely regarded as a crucial step in the last efforts to clinch a deal by next Tuesday.

An IAEA statement said Mr Amano "hopes to accelerate the resolution of all outstanding issues related to Iran's nuclear program, including clarification of possible military dimensions".

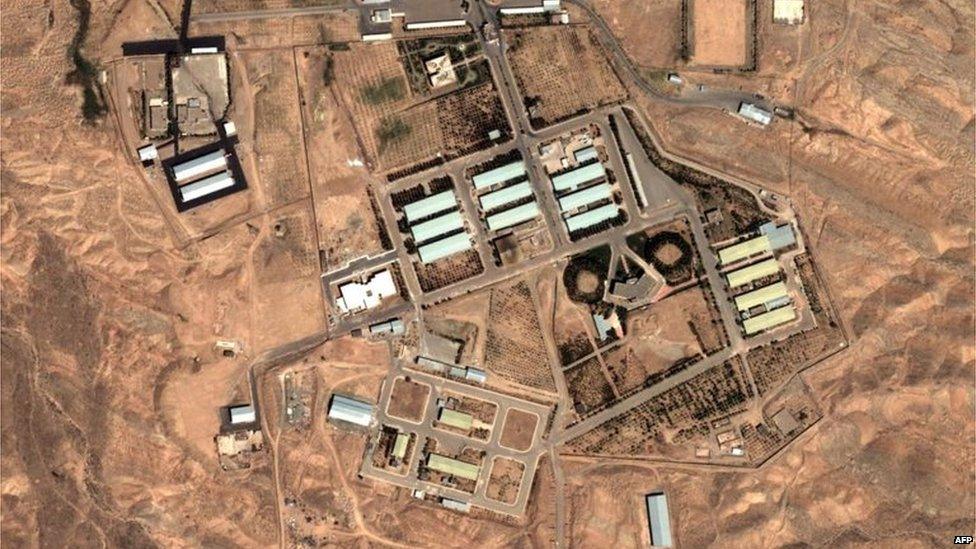

International inspections of Iran's military sites has been a key sticking point

Possible military dimensions - or PMD - are a key concern and, in any deal, the IAEA will be tasked with verifying Iran's implementation of the terms.

Under the agency's protocol, inspectors are permitted to inspect non-nuclear sites - anything from university labs to military sites - if there are grounds for concern about possible covert activities. Iran agreed to implement the protocol under the framework deal, external.

There has been discussion of "managed access" but what that means is still not crystal clear. One of Iran's key negotiators, Deputy Foreign Minister Majid Ravanchi, made it clear in an interview with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that it "isn't about letting inspectors visit and have a free hand in wherever they want to go, whatever they want to do".

Iranian officials have expressed concern about proposed IAEA interviews with its nuclear scientists to clarify questions and concerns about its past and present nuclear programme.

"They've asked to interview 18 scientists but, in the past, making names available led to the murder of scientists," says Mohammad Marandi of the University of Tehran, who is also in Vienna.

"Why do they have to enter our military sites," asks another Iranian observer. "If they have suspicions, they can take samples from outside."

Iran's Mehr news agency said Mr Amano will "receive Iran's alternative proposal" to the proposed questioning of its scientists.

Sequencing issue

Another key issue is the sequencing of the deal.

"What if Iran dismantles key parts of its nuclear programme, like the reactor at the Arak site, and then the other side decides not to lift some sanctions?" says Mr Marandi.

Barack Obama faces stiff opposition from a sceptical Congress

One source said a "creative" solution to a near-simultaneous sequencing had been found.

Iranian research and development during a 10-year deal, and what happens in year 11, is also a contentious issue.

There is a view in Iran that they can't allow a nuclear programme they insist is peaceful to simply stagnate. "We have scientists and we can't tell them not to think," many say.

As the clock ticks down to another self-imposed deadline, there is now a looming date that some call the "real deadline".

President Obama is expected to submit any agreement to Congressional oversight by 9 July for a 30-day review.

If that date isn't kept, the mandatory review could stretch to 60 days and provide a bigger window for sceptics in Congress, and in other countries, to find fault in the fine print.

"I am here to get a final deal, and I think we can," Javad Zarif, Iran's Foreign Minister and Chief negotiator, told reporters in Vienna.

"We believe we're making progress," said US Secretary of State John Kerry. "We have our own sense of deadline."