Iran nuclear deal: What it all means

- Published

In 2015, Iran agreed a long-term deal on its nuclear programme with a group of world powers known as the P5+1 - the US, UK, France, China, Russia and Germany.

It came after years of tension over Iran's alleged efforts to develop a nuclear weapon. Iran insisted that its nuclear programme was entirely peaceful, but the international community did not believe that.

Under the accord, external, Iran agreed to limit its sensitive nuclear activities and allow in international inspectors in return for the lifting of crippling economic sanctions.

Here is what was meant to happen according to the plan, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

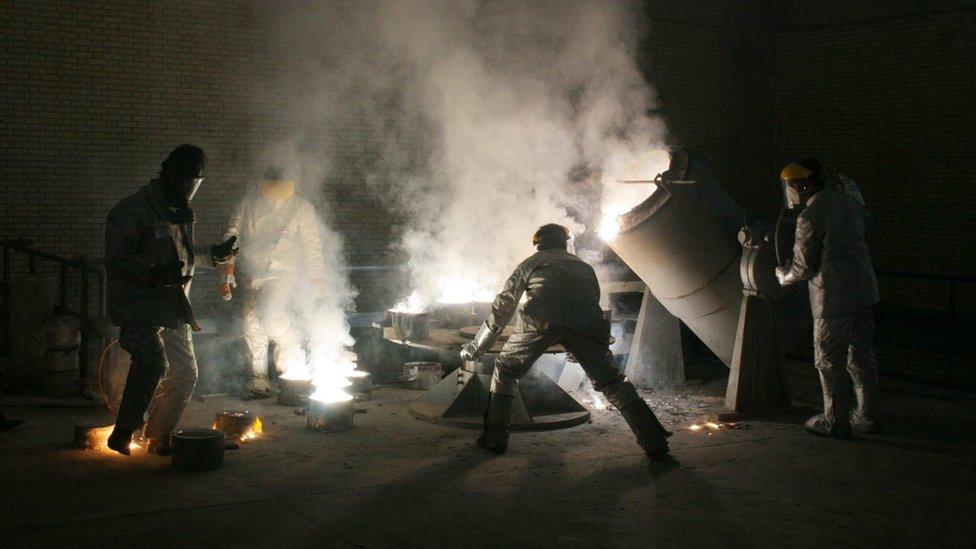

Uranium enrichment

Iran's uranium stockpile will be reduced by 98% to 300kg for 15 years

Uranium can have nuclear-related uses once it has been refined, or enriched. This is achieved by increasing the content of its most fissile isotopes, U-235, through the use of centrifuges - machines which spin at supersonic speeds.

Low-enriched uranium, which typically has a 3-5% concentration of U-235, can be used to produce fuel for commercial nuclear power plants. Highly enriched uranium has a purity of 20% or more and is used in research reactors. Weapons-grade uranium is 90% enriched or more.

In July 2015, Iran had two uranium enrichment plants - Natanz and Fordo - and was operating almost 20,000 centrifuges.

Under the JCPOA, the country was limited to installing no more than 5,060 of the oldest and least efficient centrifuges at Natanz until 2026 - 10 years after the deal's "implementation day" in January 2016.

Iran's stockpile of enriched uranium was also reduced by 98% to 300kg (660lbs), a figure that must not be exceeded until 2031. It must also keep the stockpile's level of enrichment at 3.67%.

In addition, research and development must take place only at Natanz and be limited until 2024.

No enrichment is permitted at Fordo until 2031, and the underground facility must be converted into a nuclear, physics and technology centre. The 1,044 centrifuges left at the site are allowed to produce radioisotopes for use in medicine, agriculture, industry and science.

Plutonium pathway

Iran is redesigning the Arak reactor so it cannot produce any weapons-grade plutonium

Iran had been building a heavy-water nuclear facility near the town of Arak. Spent fuel from a heavy-water reactor contains plutonium suitable for a nuclear bomb.

World powers had originally wanted Arak dismantled because of the potential military use. Under an interim nuclear deal in 2013, Iran agreed not to commission or fuel the reactor.

Under the JCPOA, Iran said it would redesign the reactor so it could not produce any weapons-grade plutonium, and that all spent fuel would be sent out of the country as long as the modified reactor existed.

Iran must also not build additional heavy-water reactors or accumulate any excess heavy water until 2031.

Covert activity

Iran is required to allow IAEA inspectors to access any site they deem suspicious

At the time of the agreement, then-US President Barack Obama's administration expressed confidence that the JCPOA would prevent Iran from building a nuclear programme in secret. Iran, it said, had committed to "extraordinary and robust monitoring, verification, and inspection".

Inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the global nuclear watchdog, were tasked with continuously monitoring Iran's declared nuclear sites and verifying that no fissile material is moved covertly to a secret location to build a bomb.

Iran also agreed to implement the Additional Protocol to their IAEA Safeguards Agreement, which allows inspectors to access any site anywhere in the country they deem suspicious.

Until 2031, Iran will have 24 days to comply with any IAEA access request. If it refuses, an eight-member Joint Commission - including Iran - will rule on the issue. It can decide on punitive steps, including the reimposition of sanctions. A majority vote by the commission suffices.

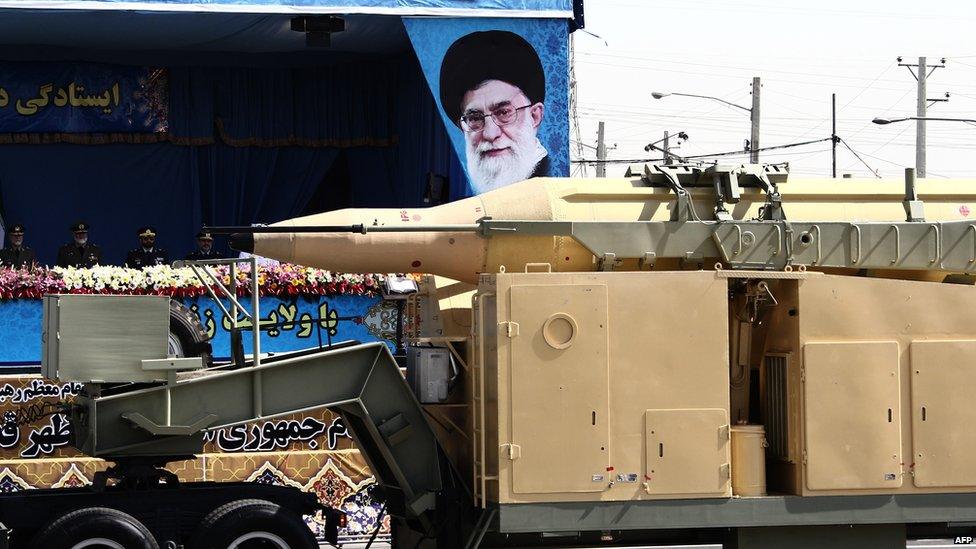

'Break-out time'

A UN ban on the import of ballistic missile technology will remain in place for up to eight years

Before July 2015, Iran had enough enriched uranium and centrifuges to create eight to 10 bombs, according to the then Obama administration.

US experts estimated at the time that if Iran had decided to rush to make a bomb, it would take two to three months until it had enough 90%-enriched uranium to build a nuclear weapon - the so-called "break-out time".

The Obama administration said the JCPOA would remove the key elements Iran would need to create a bomb and increase its break-out time to one year or more.

Iran also agreed not to engage in activities, including research and development, which could contribute to the development of a nuclear bomb.

In December 2015, the IAEA's board of governors voted to end its decade-long investigation into the possible military dimensions of Iran's nuclear programme.

The agency's then-director-general, Yukiya Amano, said the report concluded that until 2003 Iran had conducted "a co-ordinated effort" on "a range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device". Iran continued with some activities until 2009, but after that there were "no credible indications" of weapons development, he added.

Iran also agreed to the continuation of a UN ban on its imports and exports of conventional arms until 2020. Restrictions on its import of ballistic missile technology will remain in place until 2023.

Lifting sanctions

The nuclear deal allowed Iran to sell crude oil again on the international market

Sanctions previously imposed by the UN, US and EU in an attempt to force Iran to halt uranium enrichment crippled its economy, costing the country more than $160bn (£119bn) in oil revenue from 2012 to 2016 alone.

Under the deal, all nuclear-related sanctions on Iran were lifted and the country was able to resume selling oil on international markets and using the global financial system for trade. It also gained access to more than $100bn in assets frozen overseas.

However, in May 2018, then-US President Donald Trump abandoned the JCPOA, calling it "defective at its core". He reinstated all US sanctions on Iran that November as part of a "maximum pressure" campaign to compel the country to negotiate a replacement that would also curb its ballistic missile programme and its involvement in regional conflicts.

But Iran refused and saw its economy plunge into recession and the value of its currency fall to record lows, which in turn caused inflation to soar to the highest level in decades.

When the sanctions were tightened in 2019, Iran began breaching the deal's restrictions, arguing that the JCPOA allowed one party to "cease performing its commitments... in whole or in part" in the event of "significant non-performance" by others.

By November 2021, Iran had amassed a stockpile of enriched uranium that was many times larger than permitted, including at least 17.7kg (39lb) of material enriched to 60% purity - just below the level needed for a bomb. It had also resumed enrichment activity at Fordo; installed more centrifuges, and of a more advanced type, than allowed; and taken steps in the production of enriched uranium metal, which is a key material in nuclear weapons.

Iran had also significantly curtailed access for international inspectors by ceasing implementation of the Additional Protocol of its IAEA Safeguards Agreement.

Talks to save the JCPOA and bring Iran back into compliance began in May 2021, after Joe Biden succeeded Mr Trump as US president. He says the US will rejoin and lift the sanctions if Iran reverses its breaches. His Iranian counterpart, Ebrahim Raisi, says the US must make the first move.

If the negotiations were to fail and Iran was confirmed to have violated the deal, all UN sanctions would automatically "snap back" in place for 10 years, with the possibility of a five-year extension.