Will nuclear deal really change Iran?

- Published

Iran hopes for a significant economic boost

Some advocates of the nuclear deal say it will transform Iran's behaviour over time and make the Islamic republic domestically more liberal, regionally more responsible and internationally more pro-West.

Integration of Iran into the world economy may bring some social and political changes too, but for reformers the ride will not be an easy one.

Before there was a deal, Iran's opponents were talking of Tehran's ambitions to build an atomic bomb and the need to stop it.

After the deal, they moved the goalpost to the Islamic republic's behaviour, namely its poor human rights record and its regional "expansionist" aspirations, saying a deal that lifts international sanctions will empower Iran to fund the latter.

Both Iran and the US have now embarked on a mission to reassure the Arab countries of the Gulf that this will not be the case.

US Secretary of State John Kerry is touring the region trying to sell the 14 July deal - reached between Iran and the US, Russia, China, the UK, France and Germany- that limits Tehran's nuclear programme in return for the lifting of international sanctions.

"Every country engaged in this endeavour and the Gulf states hopes that (Iran's) behaviour will change," Mr Kerry told reporters , externalin Doha, Qatar.

"But we have to prepare for the eventuality that it won't," said Mr Kerry, quoting a long list of military and material support for Arabs to counter Iran's growing regional power.

As America's chief diplomat was courting the Arab countries in their capitals, his Iranian counterpart chose to do the same on a different platform.

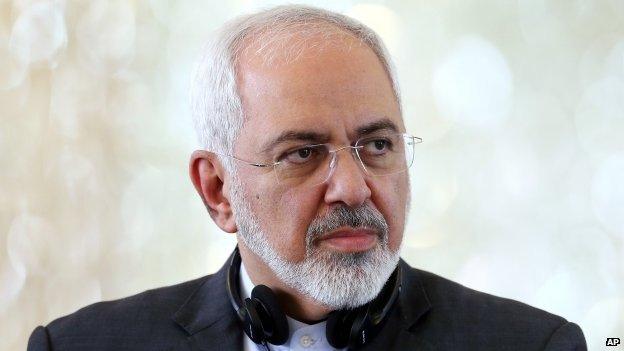

On Monday, Mohammad Javad Zarif wrote a piece published in four Arab newspapers in Lebanon, Kuwait, Qatar and Egypt.

"We must all accept the fact that the era of zero-sum games is over, we all win or lose together," wrote Zarif. , external

End of the revolution?

When grilled by US congressmen over the deal, Mr Kerry repeatedly said he hoped an Iran that rejoins the international community will not only be less of a threat to its neighbours, but will also open up to the world outside and change from within.

John Kerry has been touring the region trying to sell the nuclear deal

This is exactly what frightens hardliners within the Islamic republic.

They fear that an end to the nuclear conflict and improving ties with the US could lead to an end to a revolution that for 36 years has revolved around fighting "the Great Satan" and strictly imposing religious values on people's everyday lives.

The popularity of President Hassan Rouhani and his government is likely to rise following the nuclear deal and Iranian hardliners will try to counter this on the domestic front by actively blocking any attempts to implement social and political reform.

And they have the means to do so.

Mohammad Javad Zarif warned the zero-sum game was over

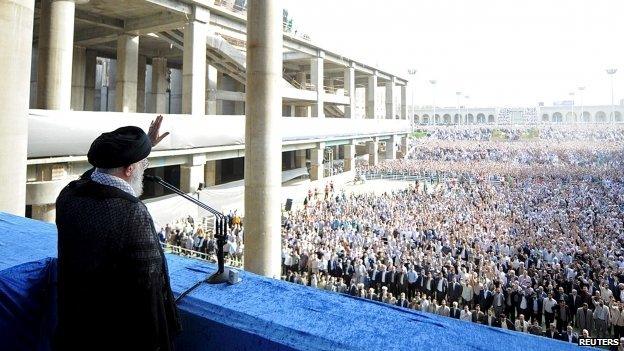

Key institutions such as the Judiciary, state radio and television, the police and the military are not controlled by the Rouhani administration, rather by conservatives appointed by the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

This strategy has been seen before. Under reformist former president Mohammad Khatami, (who led the government from 1997 to 2005) the more foreign and trade ties opened up, the more pressure was exerted on journalists and civil activists.

A crackdown on media, human rights and political activists would send a clear message to Iranians that striking a nuclear deal does not mean an end to revolutionary values.

President Rouhani's possible failure in delivering change in those areas could also fuel disappointment with his government.

The next big battleground will be the elections next February for both parliament and for the Assembly of Experts, the body tasked with appointing and supervising the Supreme Leader.

Ayatollah Khamenei has shown in the past that he prefers to balance the power of a moderate executive branch with a conservative parliament, rather than handing over both to reform-oriented forces that could weaken his own base.

Economy first

With the prospect of sanctions being lifted, battalions of foreign businessmen have been flocking to Tehran in the past few weeks trying to secure "first mover advantage" before contracts are signed.

Scores of French, German, Italian and Austrian firms have started talks with their Iranian counterparts in anticipation of the day sanctions officially end in the next few months.

Iranian officials have now revised their estimate of the country's GDP growth from the current 2% to 3-4% this year owing to increased oil revenues and access to frozen accounts.

Iran's economy:

Iran constitutes the world's biggest untapped market.

The economy is dominated by oil and gas production, with 10% of the world's proven oil reserves and 15% of its gas reserves.

The country also has vibrant scientific and telecommunications sectors.

Economic sanctions, which amounted to an almost total embargo on trade, had a huge impact.

There was a cap on oil sales, and because of banking sanctions Iran was unable to recover what money it did make from sales.

Due to its relative isolation from global financial markets, Iran was initially able to avoid recession in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, but sanctions meant that oil exports fell by half.

It is estimated that lifting sanctions will see around $120bn in accumulated foreign exchange reserves flow into the country, fuelling significant growth and potentially hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

President Rouhani's government hopes this growth will create jobs and improve living conditions for millions of Iranians.

Across the country many people share their president's hope that things will get better.

Ayatollah Khamenei remains the key figure in the future development of Iran

"If the government turns around the economy, other aspects such as human rights will get better by themselves," Mohammad, who preferred not to use his family name told BBC Persian over the phone from Tehran.

But for many others that optimism is tinged with a note of caution.

"Look at China," said Maryam another Iranian caller.

"Economic growth does not necessarily mean better human rights."