Enduring repression and insurgency in Egypt's Sinai

- Published

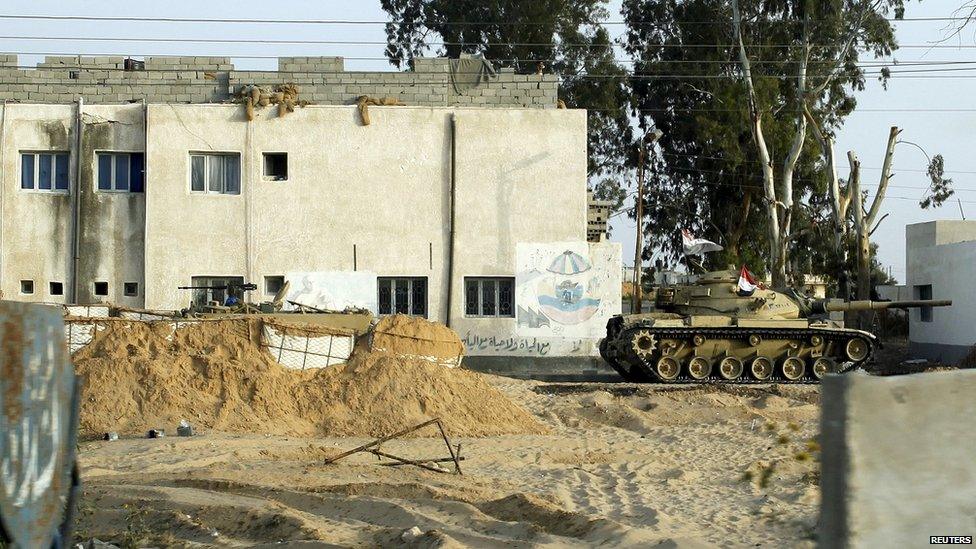

Sinai Province militants have captured sophisticated weaponry from Egyptian security forces

"They want to substitute me for the Muslim womans [sic] arrested in Egyptian prisons. These matters have to be achieved before 48 hours from now; if not, the soldiers of Sinai Province will kill me," said a man identifying himself as Tomislav Salopek in a video released on 5 August.

A week later Sinai Province (SP), a jihadist group that swore an oath of loyalty to Islamic State (IS) in November 2014, published what appeared to be a photo of Mr Salopek's decapitated body.

The photo included a caption that said the 31-year-old Croatian was killed "for his country's participation in the war against Islamic State".

Soft targets

Mr Salopek had been working as a surveyor for a French geoscience company when he was abducted while travelling on a road west of Cairo on 22 July.

His killing marks a significant change.

It is not the first time that SP has targeted foreign civilians in Egypt, but it is the first time that an insurgent organisation has kidnapped a Westerner from the capital, and then transferred and executed him in one of its strongholds.

Tomislav Salopek had been working in Egypt for the French geoscience company CGG

For SP, targeting Westerners seems to make more international headlines compared to targeting Egyptian military posts.

Foreigners and tourists seem to be seen as less costly, "soft" targets by the militants, a judgement that proved to be a miscalculation in the 1990s when the massacre of more than 50 tourists in Luxor engendered international outrage.

SP, its predecessor (that is to say, most of the factions of the Ansar Bait al-Maqdis militant group), and other groups conducted more than 400 attacks between 2012 and 2015.

The overwhelming majority targeted either military or security forces and took place in the coastal road between el-Arish and Rafah in the north-east of the Sinai peninsula.

Other attacks were conducted against Israel or soft civilian targets, such as gas pipelines.

At least 600 Egyptian security personnel have been killed in militant attacks since 2013

SP was also able to carry out significant attacks outside Sinai, most notably in Cairo, the central Nile Delta, in the north of Upper Egypt and in the Western Desert, more than 1,000km (620 miles) away from north-eastern Sinai.

Sophisticated weapons

Between 2004 and 2015, the Sinai insurgency has grown from mainly an urban terrorism campaign of bombing soft targets (such as the Taba Hilton in 2004) to a structured, low-to-mid level insurgency, aiming primarily for "hard" targets (such as Battalion 101 Camp in el-Arish, the HQ of the military campaign, dubbed "Sinai's Guantanamo" by locals).

In its attacks, SP has used anti-aircraft surface-to-air guided missiles to shoot down an army helicopter; 60mm and 120mm mortars; 12.7mm heavy machine-guns; Grad rockets to attack el-Arish's airport; anti-tank guided missiles; and various improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Since 2014, many of the attacks in Northern Sinai have been co-ordinated and simultaneous.

The most sophisticated attack came on 1 July, and saw 15 military and security posts targeted. An estimated 300 SP militants briefly occupied the town of Sheikh Zuweid.

SP has also captured a significant amount of weapons from military reinforcements sent to Sinai and displayed some of them in propaganda videos, including armoured vehicles.

In none of the previous guerrilla campaigns in Egypt have militants been able to acquire such weapons, including during the 1990s in Upper Egypt.

Counterinsurgency blunders

These disturbing developments come after more than 18 months of extremely brutal but ineffective counterinsurgency activities by the military in North Sinai.

Military operations have so far failed to quell the violence in restive North Sinai province

More than 5,000 homes have been razed to the ground, not only in eastern Rafah - to create a buffer zone along the border with the Gaza Strip - but also far away from the border, in the middle of Sheikh Zuweid, as collective punishment for families of suspects.

The regime in Egypt does not seem to recognise the new dangers. It is unwilling to review its counterinsurgency and counterterrorism policies.

"Under control is not an enough to describe the situation [in Sinai]... the situation is completely and absolutely very stable," said President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi from an undisclosed location in Sinai, while wearing military uniform on 4 July.

His statement seemed to contradict his outfit, as well as a previous declaration by his prime minister that Egypt was "in a state of war", and - most importantly - the simultaneous attacks by SP on 15 military targets three days earlier.

President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi insists that the Sinai peninsula is "very stable"

The multi-dimensional, evolutionary nature of the Sinai crisis meant that it needed a complex counterinsurgency policy, involving a broader range approaches for the mid-to-long term.

The political, social, structural, security and humanitarian dimensions of the crisis go back to the aftermath of the Israeli withdrawal in 1982.

The security and social policies since then have essentially perceived Sinai as a threat rather than an opportunity, and its residents as potential informants, terrorists, spies and/or smugglers rather than full Egyptian citizens.

Exacerbating the crisis

The main consistent feature of these security-led policies was a mix of intense repression with attempts to co-opt selected tribal leaders.

The government's policies have stoked resentment against already marginalised communities

The main result of these policies has been to turn a limited security problem related to logistical support of various Palestinian militant groups in Gaza, into a local insurgency which has steadily grown in scale, intensity, capacity and legitimacy; and which has significantly altered its purpose to bring in a complex regional dimension.

Part of Sinai's problem has to do with the structural deficiency in Egyptian civil-military relations.

This is specifically related to the lack of oversight over national security policy formulation, its execution, in addition to the general lack of accountability when such policies fail or exacerbate a crisis.

There has never been a thorough revision of the military and security policies in Sinai.

After an attack in October, Egypt declared a state of emergency in North Sinai

The only open discussion that occurred regarding Sinai was in the brief transition period between February 2011 and June 2013, and it did not yield any executive policy and died out quickly following the takeover by the military in July 2013.

Sinai's security crisis is likely to endure, as long as continuity, not change, is the main feature of military's policies in the peninsula.

Dr Omar Ashour, external is a Senior Lecturer in Security Studies at the University of Exeter and an Associate Fellow at Chatham House in London. He the author of The De-Radicalization of Jihadists: Transforming Armed Islamist Movements, and Collusion to Collision: Islamist-Military Relations in Egypt.

- Published12 May 2016