Syria war: The plight of internally displaced people

- Published

Perhaps the most sobering thing about the pictures of Syrian refugees arriving in Europe is the fact they are just the tip of the iceberg.

The United Nations' refugee agency, the UNHCR, put a number on it last week - they are only 6% of the total fleeing the conflict.

Another four million are languishing in neighbouring countries such as Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon.

And then there is a third figure which dwarfs even that - 7.6 million are displaced inside Syria itself and their plight remains very much out of sight.

The aid community has an acronym for these internal refugees - they are called IDPs or Internally Displaced Persons.

Syria now has more of them than any other country in the world.

Last week, the UN produced a map of Syria with several arrows criss-crossing it (p.7), external.

Those arrows represent the flows of Syrians fleeing violence across different parts of the country in the last six months.

After the takeover of Idlib by rebel forces in March, for example, 230,000 people ended up heading into the surrounding countryside or neighbouring provinces.

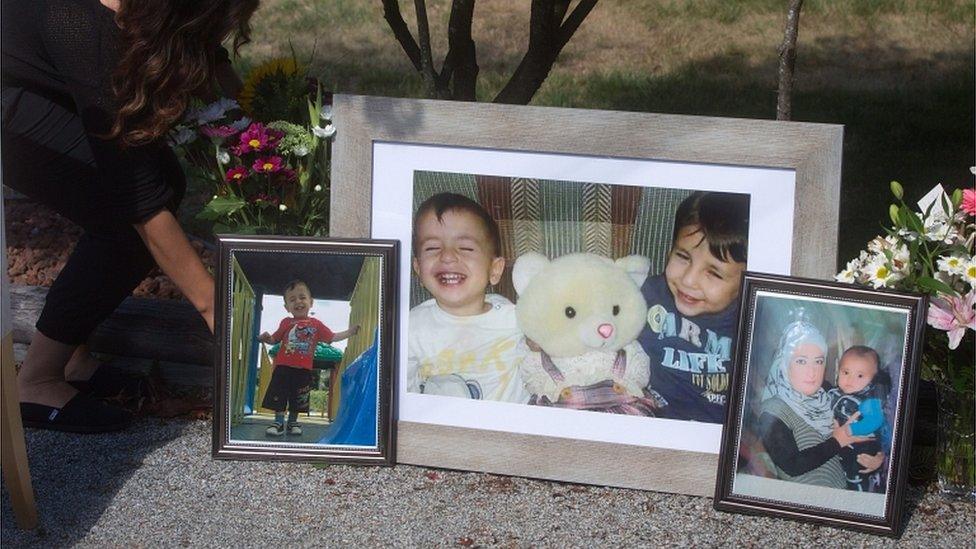

Alan Kurdi's family had tried to move inside Syria before making its fateful trip outside the country's borders

Many will have been forced to move multiple times because the battle lines have kept changing - pushing people one way and then another.

The family of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, for example, had tried moving around Syria before they finally decided to leave.

They had moved from the Syrian capital, Damascus, to Aleppo and then to Kobane.

"Generally, people try to find solutions within their own countries first," says Erin Mooney who is an expert in displacement and who has worked in Syria.

"Often they want to stay close to their homes to keep an eye on their property, perhaps hoping they'll one day move back. Now, though, the conflict is into its fifth year and people are becoming much more desperate."

But not everyone will have the option of moving across a border into a foreign country.

Some will have lost their documents, so foreign travel is inevitably hard.

Others have become besieged in areas which once were deceptively safe.

Those refugees who reach Europe often have the means to escape Syria

Very often IDPs are simply poorer than the refugees we have seen reaching the EU's borders.

"The journey to Europe is very cumbersome, and it's not cheap so you have to have a certain level of resources to do it," says Carsten Hansen, Middle East director for the Norwegian Refugee Council.

The conditions facing the displaced inside Syria are hard to illustrate through news agency pictures because these areas are too dangerous for journalists to access.

Even more worrying is the fact that aid agencies and NGOs cannot reach them either, putting them literally beyond help.

Oxford University's Professor Paul Collier, an expert on migration, says it is important that these IDPs are not forgotten just because they have not created a problem for European countries.

"They are obviously more vulnerable because they are still exposed to the violence," he points out.

"Often they can't get out. Refugees are at least relatively safe - unless they are lured onto boats by criminals."

The refugees who flee to safety abroad also have extra legal protection because of the UN's 1951 Refugee Convention which sets out their basic rights.

Those left inside Syria, on the other hand, are still formally under the protection of the Bashar al-Assad government, and for many it is his regime which has been the source of their misery.

Others will have been forced to flee their homes by Islamic State militants, like the 11,000 people recently chased out of Palmyra in May.

Experts describe the day-to-day existence of these internal refugees as being like a hidden purgatory.

Many will be living in makeshift mass shelters. They may not have access to basic amenities like clean water or electricity.

As for medical care, that too will be patchy - the World Health Organization estimates that 57% of Syria's hospitals are now out of action.

Yet helping those left in Syria remains the trickiest task of all facing the world's leaders.

"I think we use up a lot of energy talking about solving the refugee crisis, but far less focus on finding a solution to the conflict itself," says Mr Hansen.

"We need to find a way of stopping the fighting."

For those who have followed the horrors of the Syrian conflict since it began, it makes no sense to only help those who have escaped abroad because - like the Kurdi family - today's "internally displaced person" will be tomorrow's refugee.