Migrant crisis: Why is it erupting now?

- Published

Syrian and Afghan children play in a makeshift playground

They flee a country at war where the West resists any major military or political engagement.

They flee a country where Nato-led forces fought for more than a decade to achieve stability.

The stories of Syria and Afghanistan are two cautionary tales of our time.

Old wars don't end. New ones get worse.

No matter what the world's great powers did or did not do, growing numbers of Syrians and Afghans are taking their future into their own hands. They make up the two largest groups in this mass displacement of people across Europe and beyond.

Never has there has been such an ingathering of people sending the most pointed public message to their own leaders and the world at large: "You failed."

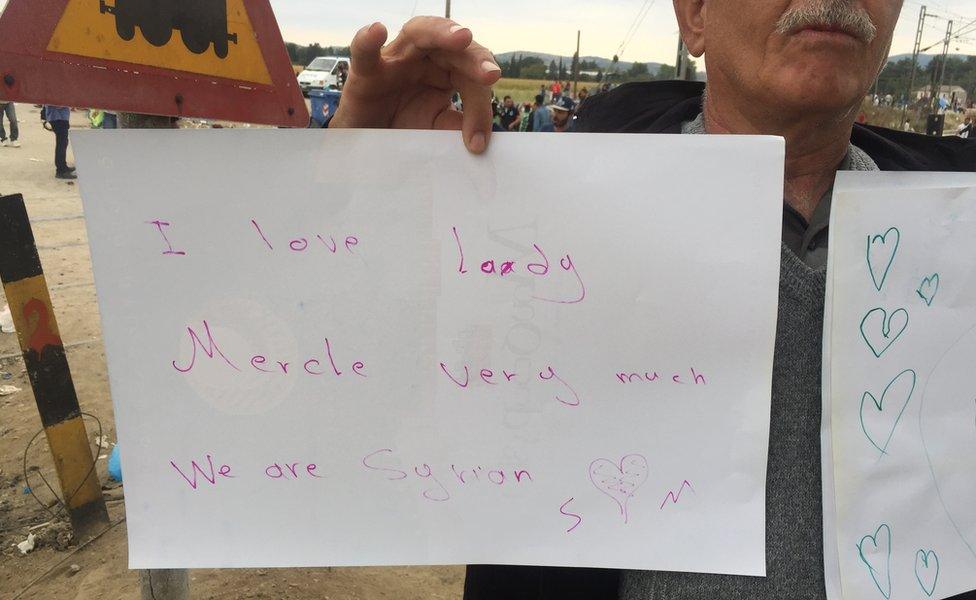

A Syrian man holds a sign declaring his gratitude to German Chancellor Angela Merkel

It's the people's version of the Live Aid concert organised by the world's musicians 30 years ago to raise money for the Ethiopian famine.

This time, people are no longer waiting for a more peaceful and privileged world beyond to come to them with aid. They're coming to that better safer place themselves - no matter what it takes.

And as this human stream rushes unabated, it starts to change course and political colour.

Now there are growing numbers of Iraqis, the other major international engagement of the decade past. Eritreans flee well-documented repression, Somalis escape a chronic instability that is now a way of life and even Pakistanis are on the move to get out of harm's way at home.

"Is there a war in Pakistan?" I ask two men who also spill out of a bus packed with Syrians and Afghans when it pulls up to the last muddy crossing in northern Greece on the Macedonian border.

"Bombs are exploding around Lahore," one young man insists, bowing his head to show me what he says is a scar on the back of it.

No easy divide

This seemingly unending flow of people making perilous journeys across the Mediterranean and running the gauntlet across northern Europe underlines how difficult distinctions and decisions will have to be made between refugees with a "well-founded fear of persecution" and those with an understandable desire to seek a better life.

But the neat binary divide between economic migrants and refugees no longer fits a messy world of fragile and failing states and "post-conflict" conflicts.

Many countries, including the United States, Britain and Canada, have made it clear they are now only opening their door to allow in thousands, possibly tens of thousands, more Syrians.

Sami Khazi Kani is trying for the second time to reach the West

"Its absolutely unfair," Sami Khazi Kani declares as he waits for his turn to cross the last metal barrier manned by Greek police.

He tried and failed a decade ago to get asylum in Britain. When he was deported to Afghanistan his risks only grew when his English language skills landed him a job as an interpreter for US troops. Now he's trying to reach the West again.

"The Taliban are killing us, the Taliban are kidnapping us," he says bitterly. "But the media only broadcast what is happening in Syria."

Taliban attacks are on the rise in Afghanistan but Syria is undeniably the war of our time. It's a country so ravaged that many dare to state the unspeakable: that Syria as we knew it is no more.

This is a place where more than half the population of 22 million people is displaced, dead or a refugee.

'Burden sharing'

It's also described as the largest, most expensive aid operation of modern times.

Even before this current crisis erupted, the world's major aid agencies had repeatedly warned that the global humanitarian system was at breaking point, cracking under the weight of Syria as well as protracted conflicts in the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Iraq and more.

"Burden sharing" has been the buzzword in aid circles for many months with growing calls for wealthy Gulf states to do more and for countries in all corners of the world to play their part.

Some countries are doing more and giving more but even the most high-profile aid operations like Syria keep running out of cash .

"Don't say there is no solution to what is a man-made crisis," Jan Egeland, the head of the Norwegian Refugee Council told me a year ago. "There are more than 190 countries in the world."

There is no humanitarian solution for this tragic humanitarian crisis

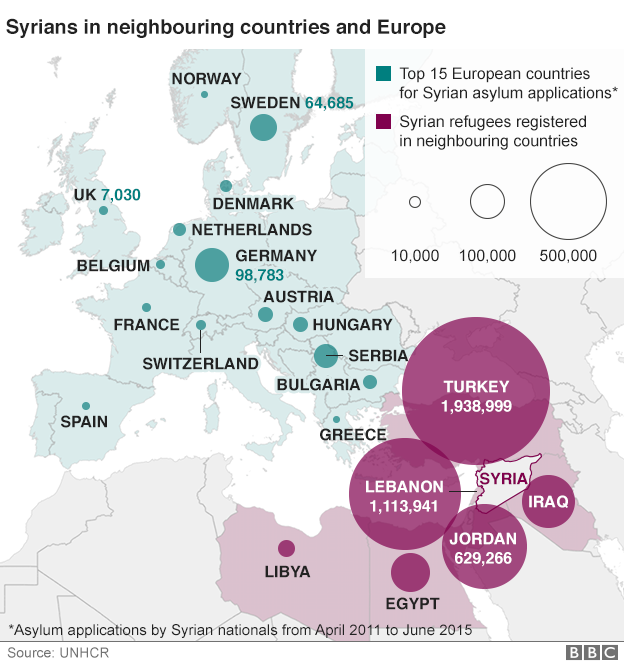

Now there's a call for quotas among European nations to share responsibility for about 160,000 refugees, mainly from Syria. But it may not work.

So when Western politicians say people must stay where they are, to be helped closer to home, their pleas now ring hollow. Governments in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, hosting the overwhelming majority of Syrian refugees, are under mounting strain.

The head of the UN's Refugee Agency, Antonio Guterres, has repeatedly invoked one mantra: "There is no humanitarian solution for this tragic humanitarian crisis." The only real solution is political.

Maps and groups

And yet, even as this crisis explodes with unprecedented human force, the fate of one man, Syria's President Bashar al-Assad, seems to matter more, to all sides, than the fate of 22 million people.

Russia and Iran are rushing to bolster the government's increasingly embattled position. Western powers focus on ramping up air strikes.

Lyse Doucet reports from the Greek border where migrants have been arriving to cross into Macedonia

The UN's new political plan is a long-term process of working groups to study a "roadmap for peace" to try to encourage warring sides to come to the negotiating table.

But Syrians, worried that aid is running out, fearful of multiplying threats from extremist forces like the so-called Islamic State, and losing hope that this war will ever end, are deploying their own maps and groups: Google maps from the internet to chart their journey to Europe and Facebook groups to get advice from those who've gone before.

And many others from many places are coming with them.

"Are you sure you will be offered asylum?" I ask a young Iraqi man from Baghdad who tells me he's exhausted after a journey that's already lasted 10 days just to get him to northern Greece.

"I am sure," he says confidently on a cold, dark night as the rain pours down on the open field. He covers his head with some plastic sheeting offered by some local volunteers and rushes to catch up with the next group making its way across a short no-man's land towards the next border.

A slogan once brandished in what was called the Arab Spring seems to have resonance again: "The power of the people is greater than the people in power."

But the lesson of that earlier moment was that those in power still have the ability to determine the people's chances to succeed, or fail.