Syria conflict: No sign of Assad regime crumbling

- Published

Predictions of the imminent, or even medium-term fall of Damascus are wrong.

It does not feel like the capital of a regime that is about to crumble.

The government-held areas that I have visited seem calm and functional. The ministry of defence, behind heavy layers of security, moves at a stately pace.

The regime has deployed some of its strongest units in Damascus because keeping the capital is so important to it.

The troops I met seemed to have good morale, in cohesive units. Their kit and weapons were well looked after; so were their positions.

One of the most strategic front lines in Damascus is in the inner city suburb of Jobar.

Government forces have clung on rigidly in Damascus, where an army recruitment drive is clear to see

The dynamic of war matters now in Syria. Not politics or diplomacy

These bracelets featuring Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrallah - a vital Assad ally - are on sale in Damascus old city

It is critical for the rebels because if the Syrian army could break through, the stronghold of eastern Ghouta would be threatened.

The regime needs Jobar because it protects the heart of Damascus; the presidential palace is only a couple of miles behind the army's positions.

Ebb and flow of war

In recent days Jaish al-Islam, one of the best organised rebel groups, has made significant breakthroughs after an attack out of eastern Ghouta.

Half of Syria's pre-war population has fled from the fighting

Syrian troops met by Jeremy Bowen have good morale, well maintained weapons and operate in cohesive units

If Jaish al-Islam can hold on to its gains, the strategic position around Damascus would change. But with the army counter-attacking, it might be just another episode in the ebb and flow of war.

Syrians in Damascus complain that the city has shrunk because four years or more of fighting in many suburbs has made them into no-go areas.

The economy has been ravaged by the war, and prices are much higher.

But the economy still functions. Farmers bring food to market. The wholesale vegetable market, which is a couple of minutes drive from front line positions in Jobar, is open.

Military assistance

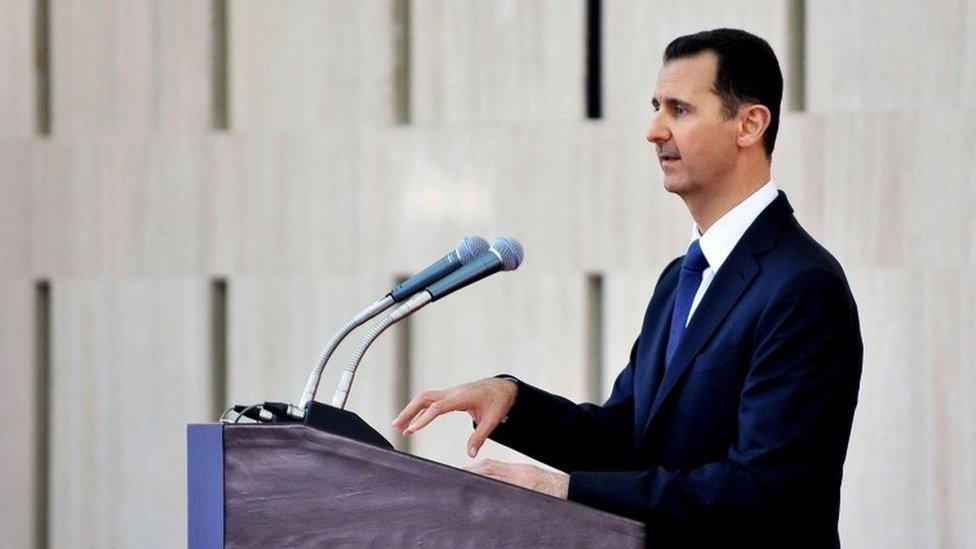

President Bashar al-Assad and his generals have had defeats this year. Idlib, a provincial capital, fell in March. The jihadists of Islamic State captured the ancient city of Palmyra in May.

But President Assad has his vital trio of supporters: Russia, Iran and Hezbollah from Lebanon. Russia seems to be increasing its military support for the regime.

Hezbollah men are fighting along the border with Lebanon. Iran provides vital financial and military assistance.

The Syrian war exports trouble, violence and refugees

Rich western countries are discovering, belatedly, what Syria's neighbours have known ever since demonstrations became an uprising and then a war in 2011.

The war exports trouble, violence and refugees. Half of Syria's pre-war population has fled from the fighting. Eight million are still in Syria, displaced, refugees in their own country. Four million have left Syria.

Britain and others hoped that helping with a relief effort for refugees would encourage them to stay put.

But hopes among refugees that the war would end relatively quickly disappeared as the killing went on.

It became clear that they would not be going home anytime soon.

Conditions in camps and temporary, overcrowded accommodation had never been easy.

The World Food Programme says it only has 40% of the funds it needs to feed 12 million people in Syria

It was even worse when it sunk in that they might face years more in camps in Jordan and Turkey, or even worse, in informal shanty towns and the slums of Lebanon.

What made matters worse was that the rich countries that funded the relief effort led by the UN agencies have made big cuts to their contributions.

The World Food Programme has cut the monthly budget to feed one person in the region from $30 to $13 (£19 to £8). In Syria, the figure is $12.50.

That is roughly the cost of three Big Macs, to feed one person for a month; it is a plain and sparse diet.

Because of cuts in contributions from donors they are struggling to do that. Hundreds of thousands of people have been told they will get no more food aid.

Complicated

One senior UN source called the lack of funding "crazy and bizarre". The source said they had been warning donors for six months that conflict and desperation would take refugees from the Middle East to Europe.

That will continue as long as the war lasts.

The war has not been contained, and continues to get worse, and more complicated. Staffan de Mistura, the UN envoy for Syria, has the toughest diplomatic job in the world.

The most powerful rebel groups taking on the Assad regime have ideologies that range from a kind of religious nationalism, to the jihadists of Islamic State who are hacking off parts of Syria and Iraq to make a new kind of political entity.

President Assad has his vital trio of supporters - Russia, Iran and Hezbollah from Lebanon

The rebel groups often fight each other. They reconstitute coalitions and organisations frequently. The rebels approved and funded by the West are not big players.

What makes things really complicated is that big regional and world powers have also intervened on either side in the war.

They include Russia, the United States, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanese Hezbollah, Jordan and Britain.

No wonder all the negotiations so far have failed. Each party to the conflict has its own agenda.

Some are opposed to each other; Iran and Saudi Arabia are effectively fighting a proxy war in Syria.

Russia and the US have other wars to disagree about as well, which has made it impossible for them to put their weight behind a serious effort to end the war, or at least to stop it getting worse.

Viewed from the battlefields I have visited in the last two weeks or so, calls from politicians a very long way from Syria for some sort of deal between the warring parties seem less likely than ever to succeed.

The dynamic of war matters now in Syria. Not politics or diplomacy.