Yemen conflict: No end in sight, six months on

- Published

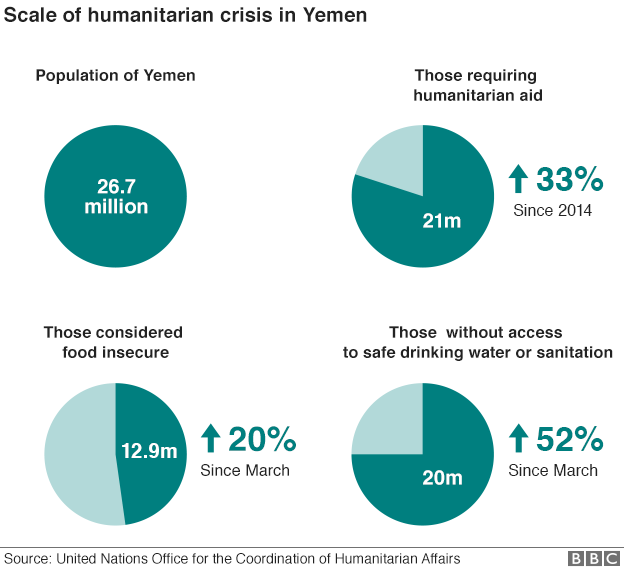

Counting the cost of six months of conflict in Yemen

In an age of 24/7 news coverage, social media and videos going viral, the war in Yemen must rank as one of the most under-reported in recent times, despite a few brave visits by intrepid journalists and film crews.

Yemen can be a remote, difficult and dangerous country to cover, and that is in peace time.

Now, six months after Saudi-led air strikes against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels began on 26 March, the war in Yemen has taken a terrible toll on the Arab world's poorest nation, with both sides accused of committing war crimes and most of the casualties being caused by the aerial bombing.

Long campaign

Six months into this war the situation is not quite a stalemate but both sides do appear increasingly entrenched.

The Houthi rebels, allied with forces loyal to the previous President Ali Abdullah Saleh, still occupy the capital, Sanaa, and much of the more heavily populated north and west of the country.

The Houthi rebel movement still controls the capital, Sanaa, and much of the north and west

Forces loyal to the president have made gains in the south and central province of Marib

Fighting them are Yemeni forces loyal to the UN-recognised President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, who has just returned to the second city, Aden, after six months in exile in Saudi Arabia.

These forces are supported by a coalition of 5,000-7,500 Gulf Arab troops led by a Saudi Special Forces commander. They have total air supremacy, having destroyed the Houthi-controlled air force on the ground.

There have been several unsuccessful attempts to broker a peace deal in neighbouring Oman. These have failed over demands that the Houthis withdraw to their northern stronghold and the Houthi demand for more power-sharing and to integrate their forces into a future national army.

Saudi officials have told the BBC that if no deal can be reached soon then Gulf and Yemeni forces will surround Sanaa and overrun it. If the Houthis then chose to stay and fight the death toll amongst civilians would be catastrophic.

The Cost

The statistics are sobering. The UN says that more than 4,800 people have been killed, including more than 450 children, and more than 24,000 people injured.

The majority of casualties have been caused by air strikes, with the Saudi-led coalition being accused by Human Rights Watch (HRW) of using cluster munitions and "indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas". HRW has also accused the Houthis of bombarding residential areas of Aden with mortar and artillery fire as well as laying mines indiscriminately.

Human toll

Casualties: 4,855 people killed, including 2,112 civilians; 24,971 injured

Internally displaced: 1.4 million

Food-aid dependant: 3,518,000

Sources: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; World Food Program - 14 September

About 1.4 million people have been displaced from their homes and more than 3.5 million now depend on food aid, yet there is still a partial blockade on the country's ports, imposed by the coalition to prevent any resupply of arms reaching the Houthis.

Many of the Houthi-Saleh arms dumps and military positions have been sited in residential areas, which have resulted in appalling casualties following coalition air strikes.

The UN has warned that Yemen is experiencing a humanitarian catastrophe

Unlike Syrians, Yemenis cannot easily flee across their land border as Saudi Arabia has partially completed a 930-mile (1,500km) border fence and reaching distant Oman entails travelling through territory controlled by al-Qaeda.

It is a sign of just how bad things have got in Yemen that many have fled by boat across the Bab al-Mandeb Strait to Somaliland and Djibouti. Some have since returned to Aden, a once thriving Indian Ocean port, now in ruins.

How did it start?

The Saudi-led Operation Firm Resolve began when Saudi warplanes struck Houthi rebel positions deep inside Yemen, taking most of the region by surprise.

Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Arab allies maintain that the conflict really began six months earlier, in September 2014.

The Houthis swept southwards from their mountain heartland and seized control of Sanaa, with the help of the ousted President Saleh, who still commands the loyalty of much of Yemen's military and security forces.

Amnesty International said last month that all parties to the conflict might have committed war crimes

By January 2015 the Houthis had placed the UN-recognised President Hadi under house arrest and by February he had fled to Aden, where Houthi forces very nearly captured him before he was rescued by Saudi Special Forces and smuggled out of the country.

The Houthis say they rebelled because of widespread corruption in government and because Yemen's federal system did not take their interests sufficiently into account.

The Saudis and their Yemeni allies contend that Iran has been arming, training and even directing the Houthi rebels, who are Shia Muslims.

But there has been little evidence of direct Iranian military involvement on the ground. The Houthi advance was enabled largely by renegade forces loyal to the previous president.

Saudi Arabia fears encirclement by Iranian proxies: in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and now Yemen.

So, a decision was taken in March by Saudi King Salman and his favourite son, the Defence Minister, Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, to draw a line in the sand and launch this war to show Iran it would not tolerate what they saw as a takeover of their neighbour by an Iranian proxy.

The Saudi-led coalition says it is defending what it calls Yemen's legitimate government

The Saudis hoped their massive, precision-guided air power would quickly force the Houthis to sue for peace.

When I interviewed their chief military spokesman in Riyadh during the first week of Operation Firm Resolve, Brig Gen Ahmed al-Asiri presented an upbeat, confidant assessment of the way the war was progressing.

But the Houthi rebels have proved more resilient than the Saudis expected, forcing them and their Sunni Arab Gulf allies to commit thousands of ground troops - and take casualties themselves.

Who is fighting who?

Broadly speaking, there are two sides in this war.

On the one side there are the Houthi rebels, who were initially able to overrun most of western Yemen with the help of Republican Guard brigades loyal to Mr Saleh.

The ex-president's role has been crucial.

Driven from power by the Arab Spring protests in 2012, he never left Yemen and appears determined to stop anyone else ruling the country in his place.

His alliance with the Houthis is considered highly opportunistic given that when he was president he fought several wars with them, calling on help from the Saudi air force - which is now bombing both his forces and the Houthis.

Leclerc tanks belonging to the Saudi-led coalition have helped loyalist forces drive back rebels from Aden

Ranged against the rebels is the Saudi-led coalition. Next to the Saudis, the most important contributors are the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which landed an entire armoured brigade in Aden, complete with French-built Leclerc tanks.

Qatar has committed at least 1,000 troops, and there is also a contingent from Bahrain. Morocco, Sudan, Egypt and Jordan are also contributing but Oman has remained strictly neutral, allowing its capital Muscat to be a convenient venue for peace talks.

Pakistan effectively snubbed a Saudi request to send ground troops after its parliament turned it down.

What about al-Qaeda?

The jihadists have benefitted enormously from the recent chaos in Yemen. Both al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and so-called Islamic State (IS) have moved into parts of southern Yemen abandoned by government troops.

AQAP now controls the eastern city of Mukalla, while IS fighters have been seen in and around Aden. Both these organisations have sent suicide bombers into Sanaa, with IS latterly targeting Shia mosques frequented by the Houthis.

The controversial CIA-run drone programme that was targeting AQAP leaders in southern Yemen is still active but is likely to have lost many of its human informants on the ground.

How will it end?

Yemen's war can only end one way - with a political settlement.

The conflict has reached 21 out of 22 of Yemen's provinces and shows no sign of ending

The Saudis certainly have both the budget and the firepower to keep prosecuting their campaign until they force the Houthis to sue for peace.

But the price will be paid by ordinary Yemenis and there are already signs of growing international disapproval of the death toll incurred on civilians by the air strikes.

The Houthis, while showing remarkable resilience, have also been unrealistic in their demands. They do not represent a majority of Yemenis and the harsh reality is that impoverished Yemen depends on its big, rich neighbour Saudi Arabia to survive economically.

The Saudis are never going to bankroll a regime (the Houthis) they see as an Iranian proxy so it can only be hoped for Yemen's sake that some compromise is reached as soon as possible.

- Published11 September 2015

- Published28 February 2015

- Published28 March 2017