IS conflict: France launches air strikes in Syria

- Published

French jets have been flying reconnaissance missions over Syria to identify targets

France has carried out its first air strikes against Islamic State militants in Syria.

French planes destroyed a training camp in the eastern town of Deir al-Zour, President Francois Hollande said.

A US-led coalition has been carrying out air strikes against IS in Syria and Iraq for more than a year.

Speaking in New York, Mr Hollande said a political solution was needed to end the Syrian crisis, but President Bashar al-Assad could not be part of it.

France, like the UK, has previously confined its air strikes against the Islamic State group to Iraqi airspace.

The UK announced earlier this month it had carried out a drone strike against two British citizens in Syria but has yet to fly manned operations in Syrian airspace.

France had previously maintained that international law prevented it from attacking targets in Syria - Paris was adamant that it would do nothing to help, even indirectly, the Assad government, says the BBC's Hugh Schofield in Paris.

But the French government has now accepted that getting rid of Mr Assad is no longer the priority and the fight against IS trumps everything else, our correspondent says.

Analysis: Jeremy Bowen, BBC Middle East Editor

Two factors have put Syria on the priority list for the leaders gathering in New York for the UN General Assembly. One is the threat posed by the jihadists of Islamic State. The other is the refugee emergency, which means that the reverberations of the Syrian war have reached Western Europe.

Now, the military priority is hitting IS.

The British hope that their new stance on President Assad might help to break the deadlock over Syria in the UN Security Council, which has crippled diplomatic attempts to find a way to stop the war.

If the rift in the Security Council over Syria cannot be repaired, Mr Cameron's call for a new diplomatic initiative to end the war won't change anything.

Diplomatic goals behind Putin's Syria build-up

More than 200,000 Syrians have been killed since the country erupted into civil war in 2011, and Islamic State took control of swathes of the country in 2014. Mr Assad has been accused of killing tens of thousands of his own citizens with indiscriminate bombing in rebel-held areas.

European leaders gathering at the UN are intensifying calls for a diplomatic push in Syria in the wake of a massive influx of refugees heading for Europe.

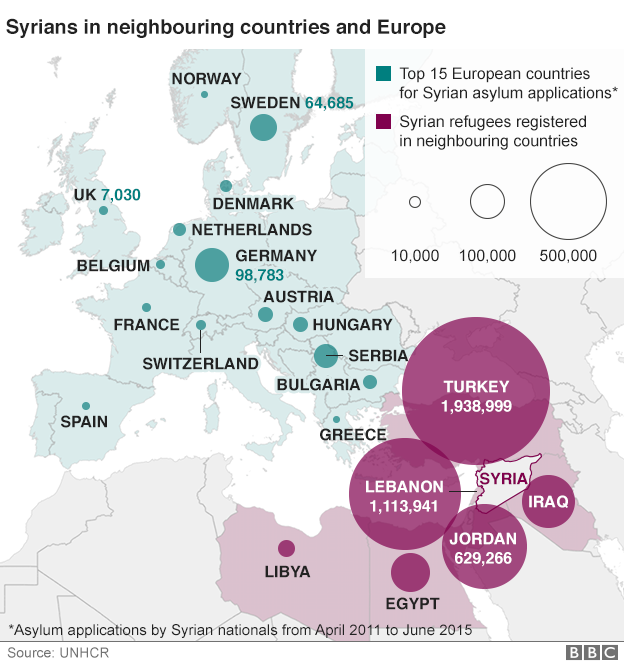

Approximately four million Syrians have fled abroad so far - the vast majority are in neighbouring Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan - and more are on the move.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron - along with US President Barack Obama and Mr Hollande - has previously demanded that Mr Assad be removed from power as a condition of any peace deal, a position consistently rejected by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In order to secure Russia's continued support, Mr Cameron is expected to soften that position this week by telling the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly in New York that Mr Assad could remain temporarily in power at the head of a transitional government.

Speaking as he arrived in New York on Sunday, Mr Cameron said: "[Bashar] Assad can't be part of Syria's future. He has butchered his own people. He has helped create this conflict and this migration crisis. He is one of the great recruiting sergeants for Isil [IS]."

The urgency of finding a diplomatic solution to the conflict has also been reinforced by Russian military build-up in Syria in support of Mr Assad's regime.

Iraq on Sunday announced that it had signed an agreement on security and intelligence co-operation with Russia, Iran and Syria to help combat IS.

Reiterating his support for President Assad, Mr Putin said Russia was co-operating with countries in the region, "trying to establish some sort of co-ordinating structure".

In an interview with CBS television, he said Mr Assad's troops - "the only legitimate conventional army there" - were fighting terrorist organisations and Russia "would be pleased to find common ground for joint action against the terrorists".

US Secretary of State John Kerry, however, said the efforts were "not yet co-ordinated" and the US had "concerns about how we are going to go forward".