Who would Russia bomb in Syria?

- Published

Vladimir Putin has said air strikes must be co-ordinated with President Bashar al-Assad's government, which the West regards as illegitimate

In the wake of their two big speeches at the United Nations General Assembly, it is probably the Russian President Vladimir Putin, rather than his US counterpart Barack Obama, who emerged the happier man.

Russia's growing involvement in Syria greatly complicates Western diplomacy in the region and may potentially even constrain the military operations of the US and its allies. It certainly requires them to maintain a level of co-operation with the Russians.

President Putin has at a stroke reduced Russia's post-Crimea diplomatic isolation, demonstrated and reinforced Russia's presence in the Middle East, and also provided an efficient and reasonably impressive demonstration of Moscow's ability to deploy military force with speed and efficiency.

Russia is also making some headway on the diplomatic front. Mr Putin's insistence that the existing state structures in Syria must be reinforced as a bulwark against the so-called Islamic State is by no means shared by the US and its allies.

But Washington and a number of European capitals are reluctantly coming to the view that President Assad of Syria may have to stick around for a transitional period. Up to now they have been insisting that as the the chief source of instability in the region, he should go straightaway if there is to be any settlement.

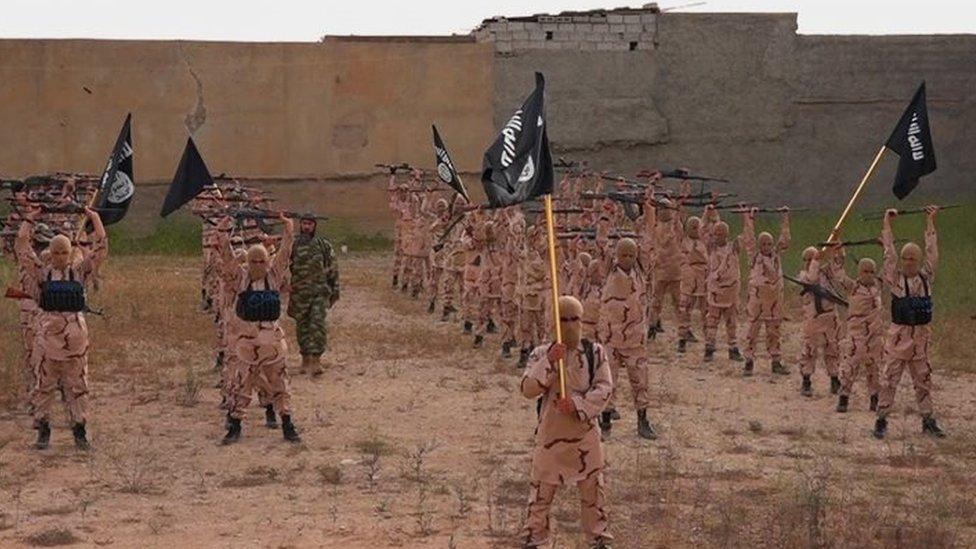

In any case, the approach pursued by the coalition assembled around Washington is not exactly a spectacular success. Air strikes against IS in Syria and Iraq are containing rather than defeating the organisation. Military operations are hampered by the absence of any reliable allies on the ground, with the notable exception of the Kurds.

Washington's efforts to arm the so-called moderate Syrian opposition have descended into near farce: tiny numbers have been fully trained and those despatched into the combat zone have largely been killed or captured, or have handed over their equipment to other militias.

Differences between Mr Putin and US President Barack Obama have been on display at the UN this week

Which targets?

So right now Mr Putin may be justified in being the happier man.

But for how long? The answer to that question depends to a great extent on what Russia decides to do next. As ever, there are more questions than answers.

Will Russia use its air power to directly intervene in the fighting?

Mr Putin seems to be suggesting that he would only do this if sanctioned by a UN resolution, though he has already deployed his aircraft to Syria under existing security agreements with the Assad regime. In legal terms he is doing nothing more than the US, which is using its air power to assist its ally - the Iraqi government.

Who might the Russians bomb? Mr Putin's rhetoric asserts that he wants a broad anti-IS coalition, so presumably it would be IS fighters that would be the target of any potential Russian attack.

But of course the Assad regime has many other enemies, many of them supported by the West, Turkey or the Gulf States. Russian strikes beyond IS would raise all sorts of problems.

Western-led efforts have so far contained IS rather than defeated it

Risks ahead

Might there be any blowback for Russia? There are broadly two cross-cutting conflicts going on in Syria: one is the wider struggle against IS; but there is also the battle between the Sunni Arab states, supported by Turkey, against Shia Iran and what are seen as Iran's proxies - Hezbollah and the Assad regime.

Mr Putin risks drawing Russia into this complex battlefield. The ostensible reason for Moscow's approach is its fear of Islamist extremism. But could its actions actually stir up more hostility that could have an impact within Russia itself?

It is Mr Putin's jets that have got all of the attention thus far. But the mention of a possible UN resolution to allow their use hints at Moscow's future diplomatic track.

A UN resolution would give a seal to Russia as a legitimate member of the anti-IS coalition (and would no doubt be used to highlight the difference between Moscow's UN approach in contrast to Washington's unilateral action).

The same UN resolution might also seek to chart a way forward towards a transitional government in Syria, without the immediate removal of Mr Assad - another Russian diplomatic goal.

But there are risks here for the Russians as well. It could get drawn into the Syrian quagmire. The Russian air force lacks many of the precision-guided capabilities and intelligence gathering resources of the US.

A Russian military involvement could be messy, stoking up antipathy both at home and abroad. Mr Putin is basking in a sense of achievement right now. But it is by no means clear that Russia's brutally pragmatic approach to the Syrian crisis is any more likely to deliver a settlement.