Jerusalem knife attacks: Fear and loathing in holy city

- Published

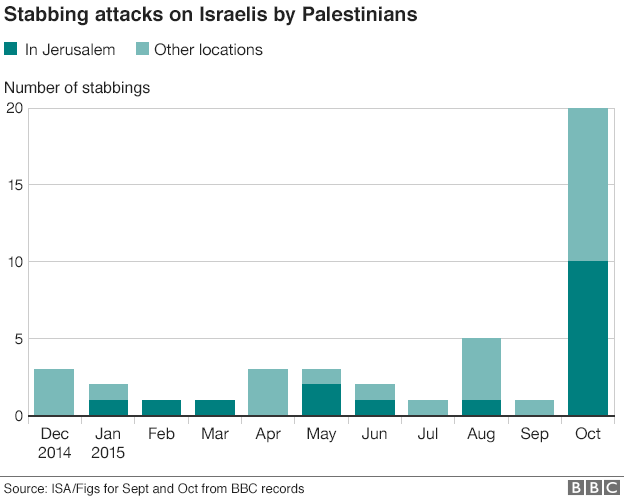

This month's wave of stabbing attacks by Palestinians has spread fear among Israelis

Jerusalem is at the heart of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. Both sides see it as their capital. Both venerate religious sites that are also national symbols.

And while it is often possible to ignore the conflict in the beaches and bars of Tel Aviv, the conflict, and the hatred it has engendered, is always strongest in Jerusalem.

Some people like to call it the city of peace. In fact, the holy city is one of the least peaceful places imaginable. Even in quiet times, conflict and hate lie close to the surface.

The scene at the main Israeli bus station in Jerusalem on Wednesday night was a microcosm of the mood of the city. A Palestinian stabbed an Israeli woman.

Police said he was prevented from boarding a bus when the driver locked the doors, then was shot dead by a special patrol unit that raced to the scene.

Israel has increased security, setting up fresh checkpoints in East Jerusalem

But fears that another assailant was on the loose in the bus station meant a security alert that lasted a couple of hours.

Emotions in the crowd that gathered outside ranged between anger, fear and defiance.

Some religious men linked arms and danced, singing Jewish songs. I saw about a dozen women, sobbing and shaking, being treated for what looked like panic attacks by medics.

Masked, heavily armed men from another elite unit of the border police ran into the building. I overheard an Israeli boy of about 12, worried, but bravely keeping it together on the phone to his mother. She must have been frantic with worry, and on her way to pick him up. The boy told her he would wait by the Lotto kiosk.

Expanding city

Jerusalem has been simmering dangerously for two years or more. The government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been asserting what it believes is its national right to build homes for Jewish Israelis wherever it decides they are needed in a city that it calls its undivided, eternal capital.

The government's backing for the expansion of settlements in the sections of Jerusalem captured during the 1967 war, and classified as occupied territory by most of the rest of the world, has transformed some districts.

Anger at the Israeli response has boiled over in the West Bank

Palestinians feel they are being squeezed out of their home. They believe that their territory is being eaten up by Israel's appetite for land, and loath what they see as a national ideology designed to enforce the dominance of Israel and Judaism.

After two weeks of violence, the Israeli government, under a lot of pressure to act from citizens who with good reason fear for their safety, has beefed up security in Jerusalem. A senior official told me that there might be no perfect security solution.

That's partly because it is harder to stop determined individuals than organisations that can be penetrated by Israel's efficient intelligence services.

But it is also because for almost 50 years, Israel has worked hard to unify West Jerusalem with the occupied east side of the city. Public transport and road systems have been integrated.

Jews have settled alongside areas that were wholly populated by Palestinians, in some cases right in the heart of Palestinian neighbourhoods.

Normal teenager

So why have Palestinians carried out appalling crimes, seemingly random attacks on passers-by simply because they are Israeli Jews? Some of the assailants have been well-educated young people without security records.

When I met Khaled Mahania, the father of 15-year-old Hassan Mahania, who attacked and badly wounded young Israelis in a settlement in East Jerusalem, he is unable to explain.

Hassan was shot dead as he carried out the attack; his 13-year-old cousin and accomplice was run down by a car and badly hurt.

The Israeli government blames the attacks on incitement by political and religious extremists. A video has circulated of a Muslim cleric in Gaza waving a knife and calling on Palestinians to slit the throats of Jews.

Khaled Mahania told me he had not replaced his son's smartphone since he broke it last year. He had no mobile internet access, and none at home.

Khaled had even thrown out the TV because he believed his children should read and talk to each other. Khaled broke down as he said his son was a typical teenager, not political and certainly no radical.

Many Palestinians have told me they believe the reason for the attacks is that another generation is realising its future prospects will be crippled by the indignities and injustice of the occupation of the Palestinian territories, including East Jerusalem.

The last straw has been the widespread belief that Israel is planning to allow Jews more access to the compound of the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, which Palestinians call the Noble Sanctuary and Israelis call the Temple Mount.

Vicious circle

Israel's use of considerable force in defence of its people also causes anger. The shooting dead of some assailants has been condemned, not least by the Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

The Israeli government denies that it plans to change the status quo around the Aqsa Mosque. It maintains that agitators have incited trouble by spreading baseless rumours.

But the perceived threat to the Noble Sanctuary is widely believed by Palestinians, not least because it comes when Israeli settlements in occupied Jerusalem have been expanding.

No public place in Jerusalem feels completely safe these days

Violence does not come out of the blue. It has a context. Once again, the problem is the unresolved conflict between Palestinians and Jews. It is at the heart of all the violence that shakes this city.

A big part of the conflict is the military occupation of the Palestinian territories, including East Jerusalem, that has lasted for nearly 50 years. It is impossible to ignore the effects of an occupation that is always coercive and can be brutal.

In successive Palestinian generations, it has created hopelessness and hatred. In some cases, that bursts out into murderous anger. Jerusalem this week is crackling with tension and hate, directed by both sides at each other.

Jerusalem's modern history is scarred by generations of bloodletting between Arabs and Jews. Death leads to destruction, to reprisals and counter reprisals and then more killing. No leader or diplomat has been able to cut through the deadly circle to make peace.

What is tragic and worrying is that just now nobody is trying.