What happens after Sinjar key to fight against IS

- Published

Sinjar is strategically and symbolically important for the Kurds

Retaking Sinjar would be extremely important strategically and for the morale of the Kurdish people in their fight against so-called Islamic State (IS) - but what happens in the days and weeks afterwards will be crucial.

The Kurdish Peshmerga had held 20% of the town since December 2014, and although there had been daily fighting since then, the two sides had been at a stalemate.

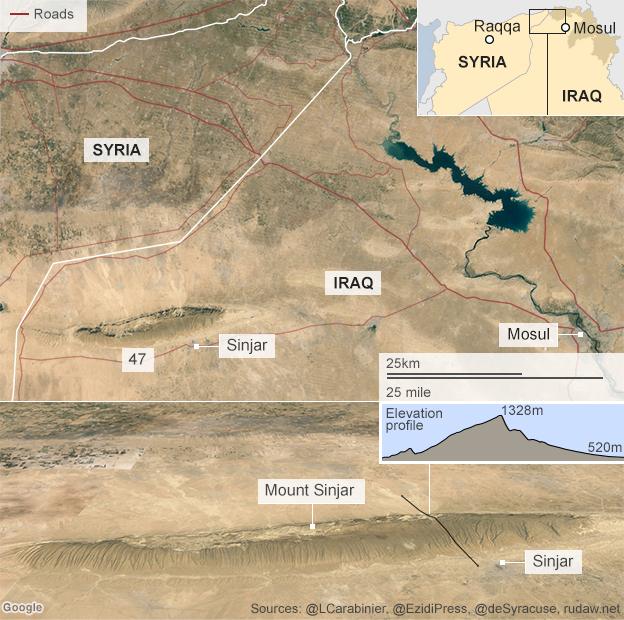

Since Thursday, though, the Kurdish forces - backed by US air strikes - have made important ground, cutting early on the Highway 47 which passes Sinjar, the main supply line between IS' self-styled capital of Raqqa in Syria and Mosul in northern Iraq.

Capturing Sinjar will not only secure the highway, but the road south of Sinjar, towards the IS-held town of Baaj, is also reported to be under control of the Peshmerga forces.

This is supposed to provide a buffer zone large enough to keep Sinjar safe in the near future.

However, it is by no means preventing IS from using scores of small countryside roads south of Sinjar that are still available until the winter weather makes them unusable.

The next step has to be against the IS-held town of Tal Afar, and then Mosul.

If not, Sinjar will always face attacks from those points. Yet, if Sinjar is de facto Kurdish territory, Tal Afar and Mosul are not.

Lingering threat

Tal Afar is populated with Arabs and Turkmen: this means that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) will not have any strategic interest in liberating and holding an area to which it has no claim.

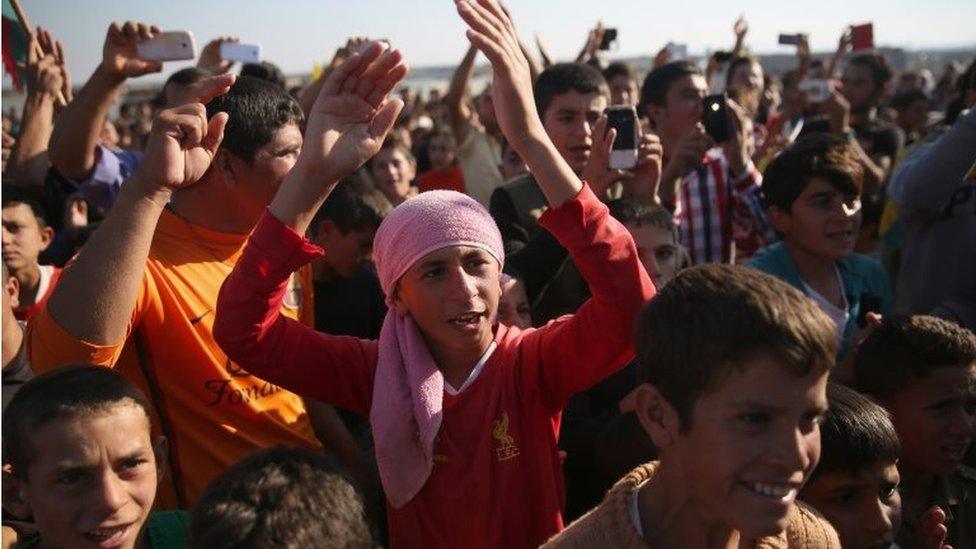

The offensive against IS in Sinjar was welcomed by Yazidis who had been forced to flee

The same goes for Mosul and Baaj. While KRG President Massoud Barzani has repeatedly hinted that his government would contribute to the retaking of Mosul, recapturing an Arab city could be perceived as an act of Kurdish aggression against Arabs, raising tensions with the Baghdad government and potentially harming the Kurdish minority that has continued to live in Mosul since IS took it.

Tactically, the town of Baaj, situated on higher grounds than Sinjar, will remain a perfect spot to target Sinjar.

Since the Peshmerga do not possess long-range missiles, how will they be able to create a strong enough buffer zone for the 3,000 Yazidis trapped on the mountain for more than a year to be able to safely return and live in their homes?

Moreover, as the IS frontline has been dissolved in Sinjar, IS is likely to return to its next best tactic: sending armoured vehicles packed with explosives to Peshmerga positions.

Once again, the Peshmerga are underequipped to face this daily threat.

Ethnic conflict fears

The impending attack on Sinjar was an open secret.

Two weeks ago, I witnessed long military convoys that were already on their way to retake the town, only to be derailed by a claim by Peshmerga rivals - Turkey's Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) rebels based in northern Iraq that it had already been recaptured from IS.

The claim did not just halt Peshmerga operations: it gave ample time for IS fighters to prepare and tactically retreat from Sinjar, just as they did in Tikrit last spring, only to take Ramadi a few weeks later.

The PKK is not the only local force that might get in the way of the Peshmerga as they seek to sustain their war effort.

Local Arab populations fear that retributions might take place against them from the Yazidi militias that have been randomly formed since the occupation of Sinjar Mountain in August 2014.

When the Mosul Dam and the Zummar areas were recaptured from IS in late 2014, Yazidi militias kidnapped Arab women, drove villagers away and looted properties. There have been reports of more revenge attacks this year., external

While KRG security forces have been trying to maintain civil peace in the area, those events have eroded social cohesion, which could sow the seeds of future ethnic conflicts.

Sinjar - a strategic town

Watch as the BBC explains the significance of Mount Sinjar

Situated in northern Iraq at the foot of Mount Sinjar, about 30 miles (50km) from the Syrian border

Highway 47, one of IS's most active supply lines, runs through the town

Area mainly inhabited by Kurdish-speaking Yazidis with Arab and Assyrian minorities

Islamic State militants attacked in August 2014

Some 50,000 Yazidis fled the town and became trapped on Mount Sinjar without food or water

Since then, Kurdish forces have won back areas of the town but IS resistance has led to a stalemate

Dr Victoria Fontan is also Director of the Center for Peace and Human Security at the American University of Kurdistan. Follow her on Twitter, external