Viewpoints: How to defeat Islamic State

- Published

UK Prime Minister David Cameron has set out his strategy for Britain to join other countries in carrying out air strikes against the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Syria.

A US-led coalition began launching air strikes on IS targets in Iraq in August 2014 and in Syria a month later.

In the wake of the recent Paris attacks, France stepped up its air campaign against IS and now Germany plans to deploy Tornado reconnaissance jets to help the French effort.

But are air strikes the best way for the West to take on the militant group? If not, what would be a better approach?

Here, several experts give their views.

Troops on the ground

General Lord Richards, former head of the British Armed Forces.

General Richards would like to see an army of about 100,000 take on IS

The events in Paris have reinforced my view that... it's very important that we seize back the initiative and the only way we can do that is ultimately by defeating them on the ground and that requires an army. Generating that army in a timely manner I think is now the issue for the world community.

The sort of army that was created to destroy Saddam Hussein's army in 2003 would carve through IS in a matter of days. Clearly, and for understandable reasons, the West don't want to put their boots on the ground, not in any numbers, therefore you have got to try to trade some alternative means of doing it. I think there's going to be a renewed focus on whether or not Western armies working with Arab allies shouldn't be deployed.

We're talking not as big as was required to defeat Saddam Hussein but still nevertheless a sizeable army. So around 100,000 is a figure that I've sort of played around with. It's got to be confident, it's got to be what we in the military call "all arms", so artillery, armour, sappers, infantry and without doubt a lot of air power - and the ability to use that air power accurately and decisively.

As everyone now knows, despite the occasional sort of early claim that it would win the day, air power alone will never win wars. It is a critical part of the panoply of war, but you ultimately need to occupy the ground in order to decide the outcome.

General Richards was speaking to BBC World Service's The Inquiry.

Military operation and political solution

Dr Victoria Fontan is a doctoral candidate in War Studies at King's College London, and is the director of the Centre for Peace and Human Security at The American University of Kurdistan.

Empowering local troops like the Kurdish Peshmerga in Iraq could be part of the solution

There seems to be a consensus that stepping up air strikes against IS is a good thing, yet we should not forget that there have been more than 8,000 US air strikes, external alone since the international reprisals against IS started in August 2014. Where are the results?

To date, IS does not show major signs of weakness. I don't think that stepping up air strikes alone will defeat the group.

At best it will make IS retreat to a smaller territory and dissolve part of its frontline. Should this happen, acts of terrorism will increase and the potential sources of danger will no longer be as tangible as they are now, with clearly established frontlines.

At worst, should areas under IS control be plundered Dresden-style, with massive civilian casualties, air strikes will heighten the popular support for IS and hence be highly counter-productive.

The solution to defeat IS is not more of the same. It is a combination of air strikes and political talks to resolve Sunni-Shia divides, as well as an empowerment of local troops like the Kurdish Peshmerga in Iraq, who have successfully been facing IS along a 1,200km frontline since August 2014. The Peshmerga have retaken the city of Sinjar recently - they should be supported to continue on their tracks.

Multi-faceted approach focusing on underlying causes

Maha Yahya is a senior associate at the Carnegie Middle East Center.

An effective anti-IS strategy has to engage with the root causes of its continued survival and growth. To grow, IS is exploiting expanding Sunni disenfranchisement.

The bulk of IS commanders and supporters [in Iraq] are either former Baath army officers, ostracised by the 2003 de-Baathification programme and dissolution of the Iraqi army, or members of Sunni tribes tormented by the governments of former Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki. In Syria, the regime's campaign against Sunni areas perpetuated a refugee crisis rather than wholesale support for IS.

IS is also tapping into a general crisis of citizenship and malaise with dysfunctional Arab governments. Indeed, it is experiences of injustice and abuse by authorities, and not poverty, that are driving disenfranchised individuals toward radical extremist ideology.

Maha Yahya believes welcoming refugees fleeing from IS will play an important role

Meanwhile in Europe, IS is building on a different crisis of identity and citizenship - particularly for second and third generation citizens of Arab descent.

A serious approach to combating IS requires a multi-faceted strategy. It needs political consensus building amongst the international and regional players involved in the Syrian conflict, including Turkey, Russia and the US, and concerted focus more on these underlying causes.

While some military operations may be necessary, the focus should be less on the reactive security-first approach that on its own offers no long-term solution, whatever tactical victories it may achieve.

Challenging the world view of IS begins by openly recognising that this is not a clash of civilizations between Islam and Christianity, but a monstrous projection of the tremendous imbalances of our world today.

In Europe, this means embracing refugees fleeing the very horrors visited by IS on Paris earlier this month and addressing the sense of exclusion and alienation, among other factors, that are driving thousands of its own citizens to join Isis.

In the Arab region, it means engaging with the root causes for IS's emergence by tackling the political and socio-economic exclusion of Iraqi Sunnis, addressing the complex Syrian conflict without maintaining the presidency and working to end the regional rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran that is fuelling much of the current strife.

Get the Sunni tribal leaders onside

Ali Khedery was the longest serving US official in Iraq from 2003 to 2010. He is now chairman and chief executive of the consultancy Dragoman Partners.

There was much scepticism in the West that tribal leaders were a viable partner to work with to defeat al-Qaeda in Iraq.

[But] I was at the table in those secret negotiations in 2005, 2006 and 2007 and I personally made those assurances: "Look, stop fighting us, let's fight al-Qaeda together, we will train you, we will provide you with intelligence, we will provide you with weapons. And then in return for defeating al-Qaeda together, we will help you reintegrate into the political process and then you can participate in your democracy."

The US has previously negotiated with tribal leaders. President George W Bush is seen here in 2007 with Abdul Sattar Abu Risha, leader of the "Anbar Awakening", an alliance of Sunni Arab tribes that rose up against al-Qaeda in Iraq. (Abu Risha was later killed by Iraqi insurgents)

Former Iraqi PM Nouri al-Maliki discriminated against Sunni tribes

And sure enough, they fulfilled their promises, we fulfilled ours to a certain extent, they won the 2010 national elections in Iraq, but then both Tehran and Washington betrayed them and brought Nouri al-Maliki back to power.

For the last five years or so, under Nouri al-Maliki in Iraq and under President Assad in Syria, the Sunni tribal leaders of both countries, and there are many of them, again faced policies of discrimination or ethnic cleansing or racial abuse by both Baghdad and Damascus. So they viewed radical Sunni groups like al-Qaeda or IS as liberators or alternatives to the sectarian central governments.

But as we saw after the 2003 invasion of Iraq, when the Sunni tribes did the same thing, eventually they turned on each other and the Sunni tribes viewed al-Qaeda in Iraq as really a scourge more than anything else. So we're starting to see the same thing now.

What you're seeing, with the breakdown of national identities and national governments, is that the tribes are proving to be among the only viable means of social order.

So it's very important that if we re-engage with the tribal leaders again, and make these same promises that this time we need to keep, that they will be able to lead their societies, that they actually have a fundamental human right of self-determination.

Ali Khedery was speaking to BBC World Service's The Inquiry.

Talk to IS directly

Padraig O'Malley is a professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston who specialises in the problems of divided societies.

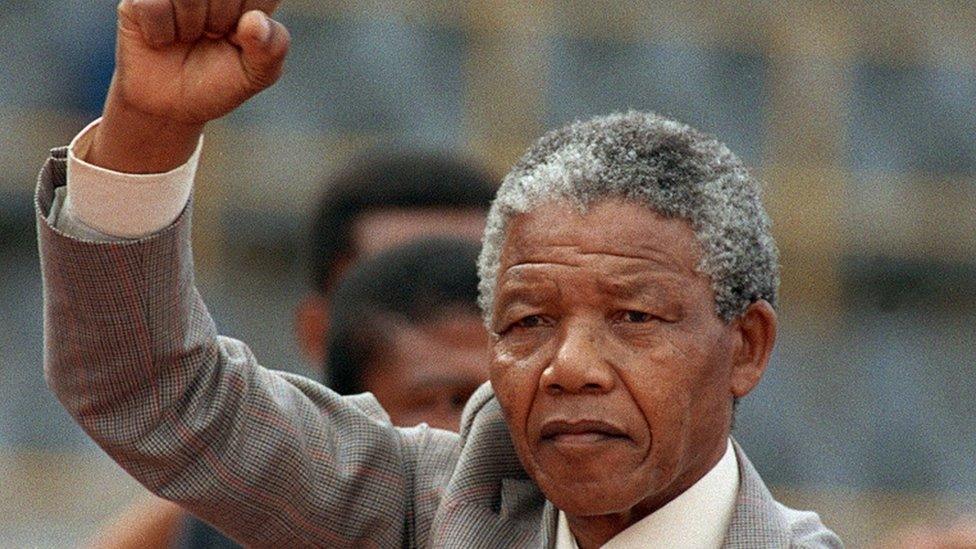

When he was on Robben Island, Nelson Mandela absorbed himself in Afrikaans, Afrikaner culture and literature, studied their value systems and modes of behaviour, and engaged Afrikaner officials sent to speak with him in endless hours of talk.

Why? Fellow Islanders asked - this total preoccupation with Afrikaners - they were, after all, the enemy?

Nelson Mandela studied his 'enemy' closely

That, Mandela responded, is the point.

Before you negotiate with your enemy, you must understand him, you must talk with him.

In our situation, IS is the enemy and all sorts of grand coalitions are being put together to bomb it out of existence.

No matter that we keep telling ourselves that no amount of bombs alone will do the job, that in the end there will have to be boots on the ground and that no partner in any coalition is willing to supply the necessary boots.

Do we really understand IS?

From the incessant flow of articles, analyses, "expert discussions", and books expounding on it, each with a different interpretation of what motivates it, where it draws its value system from, the evolution of its antecedents, what it means when it says it wants to establish a caliphate, what accounts for the skill of its combat "troops" and sophistication and slickness of its video propaganda, why there is never a shortage of youngsters eager to dress themselves in suicide belts and the ceaseless flow of recruits by some counts from 80 countries, it would seem that we should comprehensively understand the phenomenon.

But the punditry comes from armchairs, not from life within the caliphate itself.

Hence one interpretation falls over or contradicts another, some emphasise one hypothesis, and some offer another.

All have one distinguishing feature: the absence of direct contact with a broad swath of IS's disciples or, more importantly, its leaders.

And the fact is that until we find some means of talking directly to the enemy we will never understand it and hence never come up with the proper mix of policies to deal with it.

In other words, there has to be direct contact.

In a world of back channels, where sophistry substitutes for truth, the covert the new norm and the clandestine has pushed transparency aside, this is not an impossible task.

Has there ever been an "enemy" in history we have not found a way to talk to?

The Nazis? The Soviets? To mention just two that posed a far greater threat to human existence, a savagery in their disregard for human life that makes IS look like the Boy Scouts, whose victims are counted in the tens of millions.

Is it that we need an "enemy"? Or does the enemy need us? Only one way of finding out.

Talk.