Mid-East sceptical on UK role in Syria war

- Published

Syrian army soldiers patrol a bombed former fortification of so-called Islamic State near Aleppo, in northern Syria, on 2 December

As civil wars get longer, they become more complex and more intractable.

And after nearly five years of fighting, the Syrian conflict has long since passed the point where an outside power can embark on a course of action and be confident that it will have a predictable outcome on the ground.

Syria is like a broken kaleidoscope made up of jagged, overlapping fragments and when it's shaken up, the pieces move in unpredictable ways.

It is in that context that the British decision on expanding air operations from Iraq into Syria is viewed in the Middle East.

No-one believes it will be militarily decisive of course - French, American and Russian warplanes are already in action in Syrian skies after all and Britain is not talking about committing a game-changing level of air power to this complicated equation.

And there is no doubt this is a more important issue in British domestic politics than it is in the context of the Syrian war as seen from the Middle East.

But there are plenty of people who believe this is an important moment in the war.

The retired Jordanian Air Force Gen Mahmoud Idraisat - who once flew fast jets himself - put it like this.

"Militarily it's not so important," he said, "France and the United States and others have already flown 8,000 sorties and Britain will fly in a year perhaps 1,000 or 2,000. What difference will that make?"

French jets (pictured) are already in action in Syrian skies, as well as American and Russian ones

But the general was far from negative about the political implications of deeper British involvement.

It was all about deepening the involvement of another significant Middle East player who was at least trying get the stubborn pieces of that kaleidoscope moving.

There is a keen awareness in the Middle East that rich Western democracies prefer to use air-power alone in this sort of situation without committing their own ground forces.

It may be less effective but the political, military and financial costs are all lower - and so is the risk of punishment by voters if things go wrong or stretch on longer than promised.

You still need boots on the ground to win any war of course - the question is always "whose boots?"

The estimate by the British Prime Minister David Cameron that a force of 70,000 moderate rebels was ready to take on the so-called Islamic State - or Daesh as it is known in the Middle East - has been the subject of fierce debate.

The Syrian battlefield is extraordinarily complex and fragmented and there are hundreds of groups and sub-groups at play, some of them small and local, others able to call on thousands of fighters across the country.

All are united in the belief that the military and political priority must remain the overthrown of Bashar al-Assad.

Otherwise it is difficult to calibrate their positions on any sliding scale of moderation or extremism or even to place them with precision on any religious or ideological spectrum.

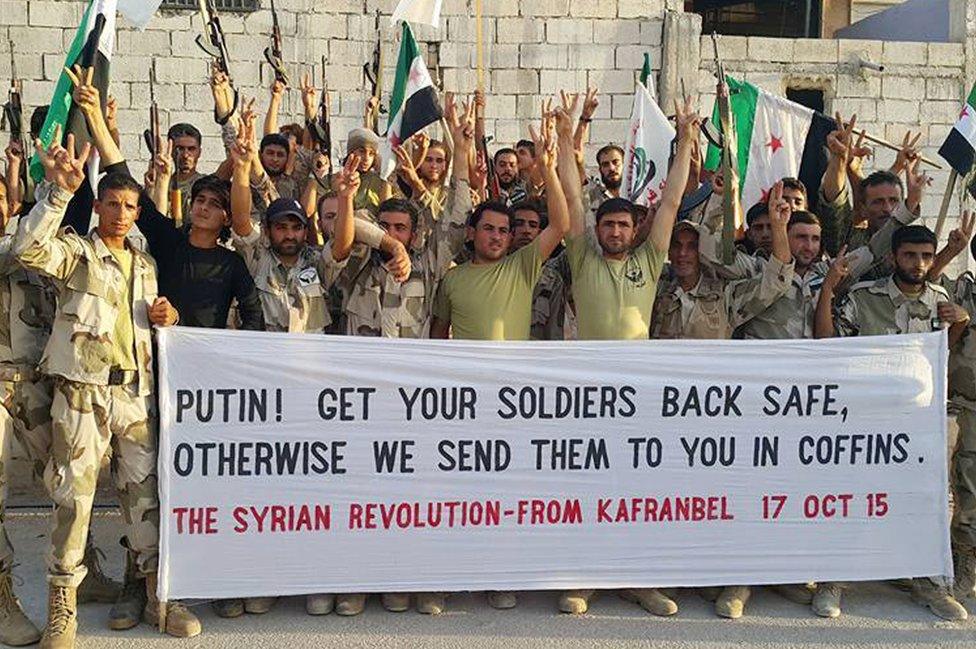

Syrian rebels are united in their determination to overthrow Bashar al-Assad - and in their hostility to his chief international ally on the battlefield, Russia

A senior official here in Jordan, speaking anonymously, said he had no doubt that there were tens of thousands of fighters who would be prepared to take on the so-called Islamic State - not least because in many parts of Syria, IS was attacking rival rebel groups rather than regime forces.

But others are much more sceptical about how numerous the forces that might be classed as moderate really are - especially in the light of the United States' disastrous experience of trying to raise, train, equip and deploy just such a force.

One Syrian opposition official here told the BBC that it was likely that there would be some kind of reckoning with Islamic State after Mr Assad had been overthrown - but he was reluctant to put a timeframe on what would undoubtedly be a messy and dangerous end-game.

Dealing with the more immediate issue, another rebel source said that Britain's original decision to confine air operations against IS targets in Iraq had not been logical when seen from the Middle East and that an expansion of air operations into Syria was both natural and welcome.

And that sums up a lot of the reaction to the British debate you hear in Amman - a wider role for the UK is seen as something to be welcomed.

But it is also seen as just another step on a long journey whose end is not in sight.

- Published2 December 2015

- Published2 December 2015