Syria conflict: 'Caesar' torture photos authentic - Human Rights Watch

- Published

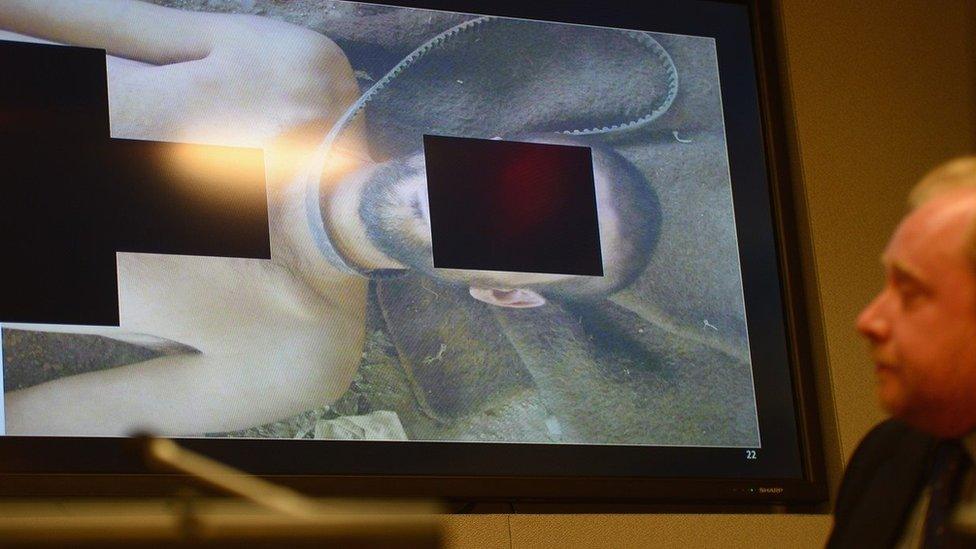

The images were presented by pathologists to the UN Security Council in April 2014

Human Rights Watch says it is confident photos smuggled out of Syria by a defector in 2013 showing 6,786 people who died after detention are authentic.

The group carried out a nine-month investigation into the 53,000 images handed to the opposition by a military police photographer, codenamed Caesar.

Researchers interviewed former prisoners, defectors, forensic experts and families of the disappeared.

Syria's government and its allies had questioned the images' authenticity.

They were first published in January 2014 in a report by three former war crimes prosecutors that was commissioned by Qatar, which supports the political and armed opposition in Syria.

In an interview, external earlier this year, President Bashar al-Assad said: "You can bring photographs from anyone and say this is torture. There is no verification of any of this evidence, so it's all allegations without evidence."

'Damning evidence'

But on Wednesday, Human Rights Watch laid out in a new report, external what it said was new evidence regarding the authenticity of the Caesar photographs, identifying a number of the victims and highlighting some of the key causes of death.

The US-based group said it had located and interviewed 33 relatives and friends of 27 victims whose cases researchers verified; 37 former detainees who saw people die in detention; and four defectors who worked in Syrian government detention centres or the military hospitals where most of the photographs were taken.

Who is 'Caesar'?

"Caesar" - seen here wearing a blue raincoat - testified at a US Congressional hearing in 2014

Source of roughly half of the 55,000 images

Military police photographer who worked for the government for 13 years

After uprising of March 2011, his job was to photograph bodies of detainees

"Significant number" of bodies show signs of starvation, other injuries include burns, bruising, gouged eyes, ligature marks indicating strangulation, and signs of electrocution, according to 2014 report by former war crimes prosecutors

Sent images to relative by marriage outside Syria

"Caesar" and family smuggled out of Syria after he feared for his safety and amid psychological strain of work

Using satellite imagery and geolocation techniques, HRW confirmed that some of the photographs of the dead were taken in the courtyard of the 601 Military Hospital in Mezzeh, a western suburb of the capital Damascus.

The group also identified a coding system for the cards placed on the bodies.

"We have meticulously verified dozens of stories, and we are confident the Caesar photographs present authentic - and damning - evidence of crimes against humanity in Syria," said Nadim Houry, HRW's deputy Middle East director.

HRW said its report focused on 28,707 of the 53,275 photos smuggled out of Syria by Caesar that, based on all available information, showed the bodies of at least 6,786 people who died in detention or after being transferred from detention to a military hospital.

The remaining photographs are of attack sites or of bodies identified by name as of government soldiers, other combatants, or civilians killed in attacks, explosions or assassination attempts.

'Nightmarish conditions'

Most of the victims were detained by just five intelligence agency branches in Damascus, and their bodies were sent to at least two military hospitals in Damascus between May 2011, when Caesar began copying files and smuggling them out of his workplace, and August 2013, when he fled Syria, HRW said.

Forensic pathologists from Physicians for Human Rights analysed a subset of the photos, and found evidence of several types of torture, starvation, suffocation, violent blunt force trauma, and in one case, a gunshot wound to the head.

Among the 27 victims identified by HRW - all of whose families spent months or years searching for news of their whereabouts, in many cases paying huge sums to contacts and middlemen - were Rehab al-Allawi, a boy who was 14 at the time of his arrest for having an anti-Assad song on his phone, and student Rehab al-Allawi, who was 25 when she was detained while working with an activist group.

The former detainees, held in the same places as most of the victims, told HRW that guards kept them in severely overcrowded cells with very little air circulation, gave them so little food that they grew weak, and often denied them the opportunity to wash. Skin diseases and other infectious diseases proliferated, and the detainees said guards denied them adequate medical care.

"Many of the former detainees who were held in these nightmarish conditions told us they often wished they would die, rather than continue suffering," Mr Houry said.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights, an activist group, has documented the arrest and detention of more than 117,000 people in Syria since the uprising against Mr Assad began in March 2011.