Iran-Saudi crisis 'most dangerous for decades'

- Published

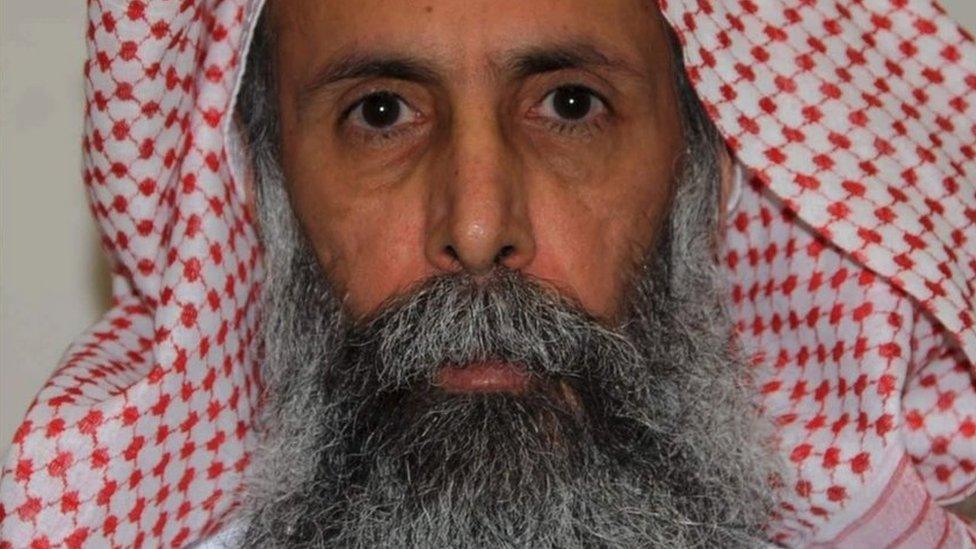

Iran-Saudi tensions boiled over with the execution of Nimr al-Nimr

Relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran are at their worst for nearly 30 years.

Tensions have spiralled following the execution of Saudi cleric Nimr al-Nimr, the subsequent setting ablaze of the Saudi embassy in Tehran, and Riyadh's expulsion of Iranian diplomats.

The struggle between Riyadh and Tehran for political and religious influence has geopolitical implications that extend far beyond the placid waters of the Gulf and encompass nearly every major conflict zone in the Middle East.

Most notably, perhaps, the crisis means prospects for a diplomatic breakthrough in Syria and Yemen now look much more remote, just as international momentum for negotiations seemed to be on the verge of delivering results.

Years of turbulence

The current standoff is as dangerous as its 1980s predecessor, which first saw diplomatic ties suspended between 1988 and 1991.

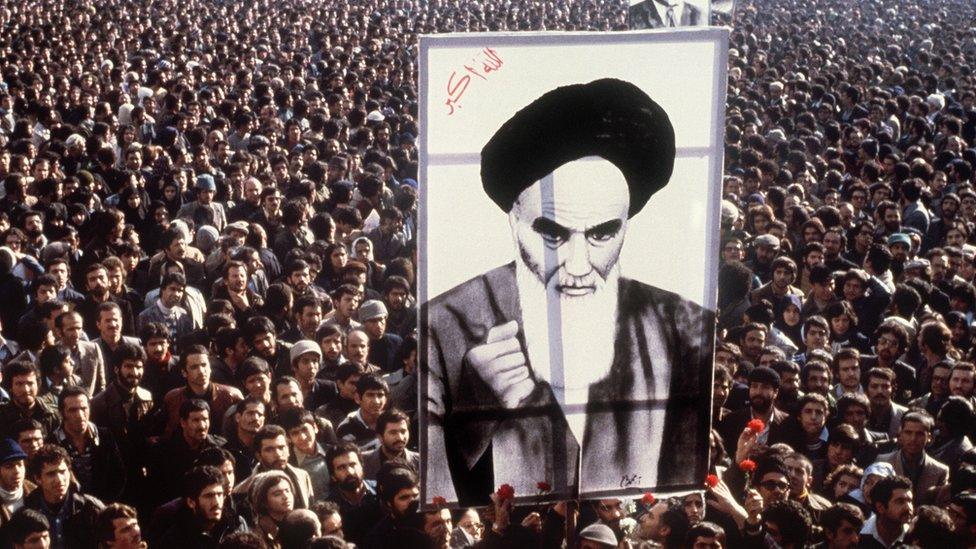

This occurred at the end of the turbulent opening decade after the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the grinding eight-year Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988.

Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states backed Iraq's Saddam Hussein during the war and suffered Iranian attacks on their shipping, while in 1984 the Saudi air force shot down an Iranian fighter jet that it claimed had entered Saudi airspace.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran drove a wedge between the two neighbours

Saudi and other Arab Gulf governments also linked Iran's post-revolutionary government with a rise in Shia militancy, an aborted coup in Bahrain in 1981, and a failed attempt to assassinate the emir of Kuwait four years later.

Meanwhile, the Iranian-backed militant group Hezbollah al-Hejaz was formed in May 1987 as a cleric-based organisation modelled on Lebanese Hezbollah intent on carrying out military operations inside Saudi Arabia.

Hezbollah al-Hejaz issued a number of inflammatory statements threatening the Saudi royal family and carried out several deadly attacks in the late 1980s as tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia rose sharply.

Deep distrust

While the current crisis lacks as yet equivalent instances of direct confrontation, tensions are as dangerous as in the 1980s for three reasons.

The first is the legacy of years of sectarian politics that have done so much to divide the Middle East along Sunni-Shia lines and foster an atmosphere of deep distrust between Iran and its neighbours across the Gulf.

Iran and Saudi Arabia support opposing sides in conflicts in Yemen and Syria

In such a supercharged atmosphere, the moderate middle ground has been sorely weakened and advocates of a hardline approach to regional affairs now hold sway.

Second, the Gulf states have followed increasingly assertive foreign policies over the past four years, partly in response to what they see as perennial Iranian "meddling" in regional conflicts, and also because of growing scepticism about the Obama administration's intentions in the Middle East.

For many in the Gulf, the primary threat from Iran lies not in Tehran's nuclear programme but in Iran's support for militant non-state actors such as Hezbollah and, more recently, the Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Both the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen and the multinational coalition against terrorism announced last month by Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman show Saudi officials in no mood to compromise on regional security matters.

'Death knell'

Finally, the breakdown in diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran probably sounds the death-knell, at least for now, for regional efforts to end the wars in Yemen and Syria.

Lost in the furore over the execution of Nimr al-Nimr was an announcement that the fragile ceasefire agreed in Yemen on 15 December had broken down.

Neither the ceasefire nor the UN-brokered talks that started at the same time had made much headway, and while the UN talks were due to resume on 14 January that is unlikely if the Saudi-led coalition and Iran intensify their involvement in Yemen.

A similar outcome may now await the Syrian peace talks due to begin in Geneva in late January, as weeks of patient behind-the-scenes outreach to align the warring parties will come to nothing if the two most influential external parties to the conflict instead double down and dig in.

Kristian Coates Ulrichsen is the Research Fellow for the Middle East at Rice University's James A Baker III Institute for Public Policy and an Associate Fellow with the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Chatham House. Follow him on Twitter, external.

- Published2 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016