Iraq divisions undermine battle against IS

- Published

IS has lost 40% of the territory it once controlled in Iraq, the US-led coalition says

More than in any other country, Iraq's future is intimately bound up with the fate of self-styled Islamic State (IS).

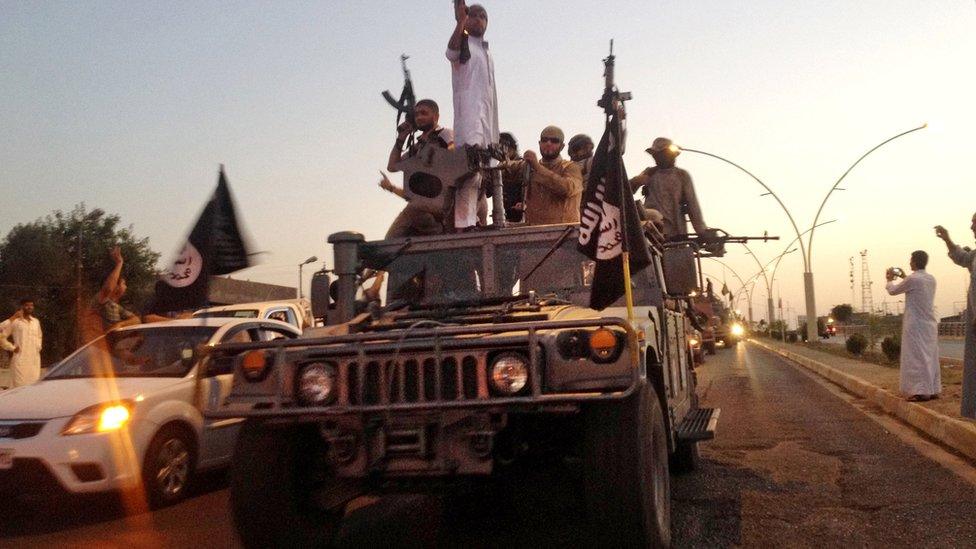

Militants from the group swept virtually unopposed into large swathes of the country, including the second city Mosul, in June 2014.

Their gradual expulsion from Iraq seems at the moment to be almost a matter of time, albeit a good deal of time.

Territory that was lost in a day or two is taking many months to claw painfully back.

If that process continues and the militants are defeated, the way Iraq fits together - if it does - will be decided by who pushes them out, and how the resulting vacuum is filled.

Slow progress

The IS fighters were able to lodge so easily in the Sunni Arab heartlands because the people there had been largely alienated by the sectarian policies and practices of the Shia Arab-dominated Baghdad government under Nouri al-Maliki, who was finally prised out of the prime minister's office in August 2014.

Precious little has been done since then to foster national reconciliation and make the Sunnis, a powerful minority under Saddam Hussein, feel they are full partners in a national project.

Iraq's Sunni Arabs have long complained of marginalisation by the Shia-led government

Legislation to empower the Sunnis by devolving security and financial responsibilities to the provinces has not happened.

Nor have measures to reverse the persecution of former members of Saddam Hussein's Baath Party, or the random arrests, detentions, and to assuage other Sunni grievances.

While slow progress is being made to drive IS back, many argue that military victory alone is not enough.

"Unless there's political reconciliation, we'll have IS back again five years down the line," a senior diplomat warned.

It happened before, so the historical lesson is there, and not so long ago.

The predecessor of IS, al-Qaeda in Iraq, was driven out of the mainly Sunni western province of Anbar from 2006, after the local tribes were induced to switch sides and fight alongside the US and Iraqi militaries against the militants.

Islamic State militants took control of much of northern and western Iraq in June 2014

But promises of employment and empowerment were not kept. Mr Maliki's policies so angered many Sunnis that the terrain was soon ready for the militants to move back in from refuges in Syria.

The US, who have about 3,500 military personnel training and advising Iraqi government forces on the ground, also seems to be aware that military muscle is not enough.

"We can't just kill our way out of this one," said Col Steve Warren, spokesman in Baghdad for the US-led international coalition against IS.

"We need good governance, a peace settlement in Syria, and other things to fall into place."

Neither of those elements is currently available. But the fight against IS goes on, and looks set to be stepped up.

Militia challenge

There is a strong feeling that the Americans are pushing for a major victory such as the recapture of Mosul and possibly Raqqa in Syria - IS's self-declared "capital" - as a legacy item before President Barack Obama bows out in January.

Shia militias have been accused of human rights abuses against Sunni civilians

But even if initially successful, such an ambitious project, indeed, any further moves to oust IS, could go badly wrong if the foundations are not sound.

Mosul is an almost wholly Sunni city with a population of about two million.

Some residents may still see IS - about 85% of whose fighters in Iraq are believed to be Iraqi - as their protectors against an Iranian-backed, Shia-dominated Baghdad government.

But even without that, if the city is destroyed and occupied by outsiders such as Kurds, Shia militias, or US-backed Iraqi army forces, the seeds of resentment and another militant resurgence could be sown.

The success of military moves against IS so far gives mixed portents.

When the Iraqi army collapsed like a house of cards in the face of the IS eruption in June 2014, it was a motley array of hastily-assembled Shia irregulars, loosely banded into the Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation) that prevented the militants reaching Baghdad.

They also spearheaded the "liberation" of the first province to be largely cleared of IS fighters, Diyala, north-east of the capital, a mixed region with a patchwork of Sunnis, Shia, Kurds and others.

Only now, a year later, are Sunni families being encouraged to return, and very much under the aegis of the Shia armed factions.

When a ceremony was staged recently in the town of Udhaim to welcome hundreds of Sunni families back, it was attended by senior Iraqi army and police officers, and by Sunni tribal sheikhs.

But there was no doubt about who was the star of the show: Hadi al-Ameri, whose Iranian-backed Badr Organisation is one of the lynchpins of the Hashd, which clearly calls the shots in the province despite army and police presences.

In nearby Salahuddin province, less mixed and more Sunni, the picture is essentially the same.

In its capital Tikrit, Saddam Hussein's old hometown, some 80% of the largely Sunni population is believed to have returned.

But they now live under the flags and banners of the Shia militias who are still there, some of them accused of stealing cars and kidnapping for ransom - a growing phenomenon in the Shia areas of Baghdad and elsewhere where they also proliferate.

Although there is some attempt to set up a Sunni Hashd in Tikrit, disgruntled Sunnis say it is controlled by the Shia, so recruitment is low.

Some Sunni tribesmen have volunteered to fight IS militants, as the did against al-Qaeda in Iraq

"Shia militias are everywhere, but there is not a single group of armed Sunnis in Baghdad, Diyala or Salahuddin," grumbled one senior Sunni politician.

"That leaves IS as the only Sunni militia."

But the template was quite different for the latest blow against IS: the recapture last month of Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province.

A Sunni stronghold, Ramadi, fell to IS last May, after the Iraqi army collapsed again.

This time, the campaign to recapture it was spearheaded not by Shia militias, but by government forces backed by coalition air strikes.

The main shock troops were the elite units of the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service, a US-trained outfit answering directly to the prime minister.

Iraqi army and police forces filled in, and Sunni tribal fighters also played a role.

Elite Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service led during the government's assault on Ramadi

"Make no mistake, the recapture of Ramadi was a turning point in this campaign," exulted the commander of coalition forces, Lt-Gen Sean McFarland.

"The enemy suffered devastating losses and the Iraqi Security Forces have proven themselves capable of defeating Daesh [IS], even when the enemy has all the advantages of prepared defence in an urban area."

It was a testing-ground for a narrative other than that of the Iranian-backed Shia militias, who were held back, although they say they played an important role in securing springboard bases for the offensive.

'Mobilising the nation'

Ramadi gave a boost to the embattled Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi.

He has scant support even from his own Shia Daawa party, and is seen across the board by Sunni, Shia and Kurdish politicians as weak, hesitant, lacking in leadership and unable to stand up to the militias.

But there was a down-side to the Ramadi victory too: heavy destruction, and the displacement of the entire population.

Large parts of Ramadi were destroyed during the battle for the city

"It's completely destroyed, and the people have been displaced and mistreated, dealt with like IS suspects," said a disgruntled Sunni politician.

"People inside Mosul and Falluja [another IS-controlled city in Anbar] will be asking: 'What did you get?' Military operations are useless unless you make people feel they're first-class citizens.

"Unless there's an internal revolt from inside Mosul, people will feel this is not the army of Iraq, it's just another army killing more Sunnis."

Nor can the formula that finally and slowly worked in Ramadi simply be applied at Mosul. It took government forces with coalition backing seven months to regain Ramadi. Mosul is 10 times bigger.

"Neither the army, nor the police, nor the Hashd, nor the tribes, can do Mosul on their own," said Hadi al-Ameri of the Badr organisation.

"We have to work together as one cohesive team, in co-ordination also with the [Kurdish] Peshmerga forces, to mobilise the whole nation to defeat IS."

Haider al-Abadi is seen by Sunnis as unable to stand up to the Shia militias

He omitted to mention coalition air support, which would also clearly be crucial to the campaign.

Some Iraqi analysts believe outside ground forces would also be needed. US military leaders, while reticent, clearly want to up the pace and have not ruled out more boots on the ground.

In the absence of serious moves towards national reconciliation, one senior government figure also saw a campaign to retake Mosul as a vital way of forging national unity.

"Reconciliation is not moving ahead. The only way forward is to defeat IS in Mosul. Some Sunnis believe IS is their protector, as long as the government and the Hashd are as they are.

"The only way to win them over and have reconciliation and bring new leaders is to get IS out of Mosul."