Islamic State: The struggle to stay rich

- Published

IS territorial control in Iraq and Syria has shrunk since its peak, according to the US-led coalition

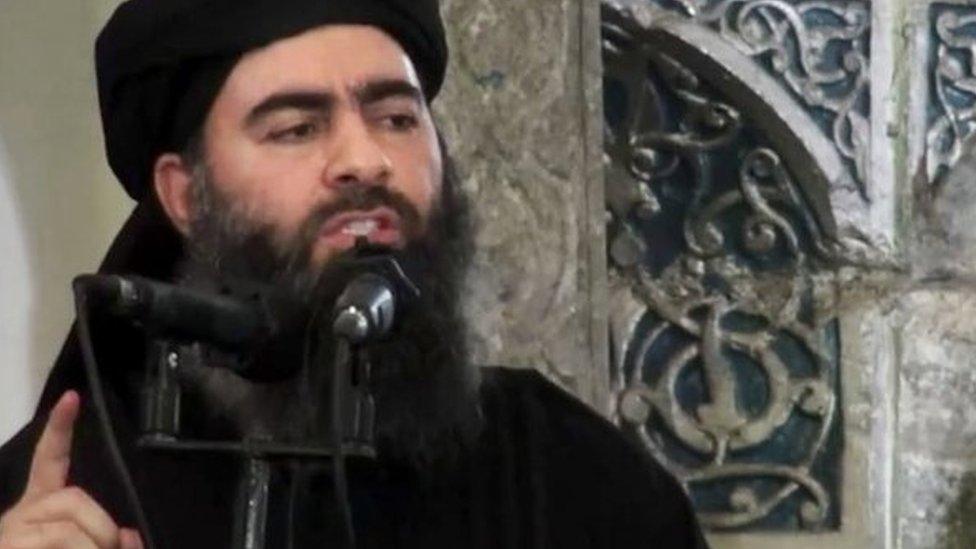

Since its leader, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, declared the so-called Islamic State (IS) caliphate in June 2014, the world has looked on as the group captured towns and territory, attracted fighters from across the globe and committed atrocities against anyone failing to adhere to its extreme interpretation of Islam.

But over a year-and-a-half later, despite territorial losses, the group survives, thanks in no small part to its status as "the best-funded, external terrorist organisation" in history.

Whilst most people decry the validity inferred from the name of IS as a "state", the group's financing is certainly more reminiscent of a state than that of organisations such as al-Qaeda that relied heavily on donations to fund their operations.

IS finance comes from a number of main sources:

ongoing oil revenue

taxes and property confiscation

gains it made from grain silos, banks and oil storage facilities when it first overran the Syrian and Iraqi territory it now occupies.

In areas under its control, IS controls trade and collects taxes and fees

Donations are noticeable by their absence.

The areas controlled by IS contain extensive oil wells and gas supplies, including storage facilities, that the group was able to tap when it first took control.

It has, since the summer of 2014, effectively exploited these supplies to provide fuel for its operations, the local people, for the cross-border smuggling routes into Turkey, and, in a marriage of convenience, the Assad regime itself.

The US Treasury estimates that, prior to the start of US-led coalition's bombing campaign targeting oil installations and tankers in October 2015, the oil and gas business provided as much as $500m (£354m) annually, external.

The Treasury also estimates that IS generates "hundreds of millions per year" from the taxation and extortion of the population living in the regions it controls, profiting from local financial and commercial activity, selling permits for antiquity excavation and charging tolls on transport crossing its territory.

The group even taxes the salaries of Iraqi government employees working in IS-controlled regions, who, until August 2015, were still paid as much as $170m per month by the Iraqi Government.

IS is also estimated by the United Nations to have made as much as $45m from kidnap-and-ransom, external in 2014.

State-like aspirations

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared a caliphate on the territories seized by IS militants

Whilst establishing definitive numbers is impossible, at its financial peak in early 2015, IS reported an expected surplus of $250m after budgeting for expenditure of $2bn, including countless spending commitments, external such as monthly wages for the poor and disabled, orphans, widows and families of individuals killed in air strikes, as well as the provision of food and commodities in the markets.

The Iraqi government itself had previously announced a budget of well-over $2bn, external for the governorates in Iraq that were subsequently overrun by IS.

Whilst aspiring to provide the services of a proto-state, IS is also engaged in a relentless military campaign - action that is not cheap.

As well as maintaining military capabilities on multiple fronts and paying and providing for fighters, assaults such as the failed months-long siege of Kobane have sapped the group's resources.

Furthermore, the spare parts and expertise needed to maintain the oil infrastructure on which so much IS financing relies are, if available, a further drag on its funds.

And herein lies the rationale for the relentless focus on IS funding by the international community.

A group aspiring to the status of a self-supporting state has significant financial outlays that provide potential points of weakness to be exploited in the struggle to thwart its ambitions.

The response of the international community thus far has included:

countless UN Security Council resolutions - most recently UNSCR 2253 in December 2015 following the Paris attacks - passed in an attempt to instil a global response to IS financing

a Counter IS Finance Group, led by Saudi Arabia, Italy and the United States, bringing together over 30 countries, external, established in an attempt to co-ordinate a concerted effort to disrupt and degrade IS' sources of funding

the mobilisation of the private sector through the work of the Financial Action Task Force, external, in an attempt to disrupt IS' access to the international financial system

Tide turning?

So what of the group's finances today? The "one-off" successes from capturing bank vaults, oil storage facilities and grain silos as territorial gains were made, have not been repeated.

Indeed, IS territorial control is down 40% and 20% in Iraq and Syria respectively since its peak, according to the US-led coalition.

In an effort to restrict IS' fundraising ability:

oil facilities and transportation have been bombed by coalition air strikes

bulk cash storage sites have also been targeted, incinerating millions of dollars

the Iraqi Government has suspended payments of state-employee salaries in IS-controlled territory

brokers and middlemen feeding the IS economy have been sanctioned by the UN

and the Iraqi Central bank and international financial community have redoubled their efforts to ensure IS is isolated from the financial system by cutting off a raft of exchange houses and banks in IS territory

In sum, since IS was declared the best-funded terrorist group ever faced, the international community has, as never before, focused on disrupting and degrading a terrorist group's finances.

A recently announced 50% salary cut, external for IS fighters suggests that perhaps, at last, in Syria and Iraq, the financial tide is turning.

Tom Keatinge is Director of the Centre for Financial Crime & Security Studies at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi). Follow him on Twitter, external