Practising medicine under fire in Yemen

- Published

Three MSF hospitals and one ambulance were hit by air strikes in three months

Mariela Carrara was just days into her posting as an emergency doctor at the Al-Jumhori hospital in Saada, northern Yemen last May when a husband and wife were rushed into the building.

They were young, no older than 35. Their family home had been hit by an air strike, they said, one of thousands launched by a Saudi-led coalition that pounded the province every day that month.

The heartland of the rebel Houthi movement, Saada is among the most dangerous parts of Yemen, and the Al-Jumhori is the only emergency facility in the province — in reality, the only A&E department in most of northern Yemen.

Dr Carrara, an Argentine working for the international medical charity Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF), triaged the married couple. The husband's injuries were minor and she turned her attention to the wife, who had severe injuries to both her arms. Nearly all the soft tissue had been stripped away by the blast.

As a surgical team prepared to amputate, Dr Carrara spoke to the woman's husband. He asked her to save his wife's arms. Their four children, all younger than 10, had been killed by the strike, he told her.

"We have lost our children," he said. "Please do everything you can."

Dr Mariela Carrara is nearing the end of a six-month stint for MSF in war-torn Saada City

Since March, when the Saudi-led, US-backed coalition launched a military campaign to defeat the Houthi rebel group, some 6,000 people — almost half of them civilians — have been killed in air strikes and fighting on the ground in Yemen, according to the UN.

In January, a leaked UN report accused the coalition of "widespread and systematic" attacks against civilians. The coalition says it regrets civilian deaths, which it insists are unintentional.

The coalition is attempting to restore the internationally-recognised government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, who was forced into exile by the rebels last March, but the conflict has taken a bloody toll on the country's civilians and ravaged an already fragile health system.

Three MSF facilities and one ambulance have been hit by air strikes, killing at least eight people and depriving hundreds of thousands of access to emergency care — despite the charity providing their co-ordinates to all sides.

The aftermath of an air strike in the distance behind the Al-Jumhori hospital, right

With precious few A&E facilities left functioning, Al-Jumhori has expanded from a small facility into a 93-bed hospital treating 2,000 emergency cases a month and performing more than 100 surgeries a week.

"I'd never before seen the level of casualties I saw in Saada," Michael Seawright, an MSF project coordinator, said in January after a stint in the province.

"The scale of wounded was extreme in two respects - firstly there was a large number of wounded coming through the hospital, but second the severity of wounds was also often extreme."

And the bombs have other crippling effects, beyond their blast radius. They discourage many casualties from even attempting to reach a facility, said Teresa Sancristobal, MSF's emergency co-ordinator for Yemen.

"The perception is that the medical facilities are not safe. A lot of times when we ask patients why they didn't come sooner, they tell us they were afraid," she said.

The team at the Al-Jumhori are a mixture of local doctors and MSF's international staff

For Yemen's civilians, getting to a medical facility equipped to cope with severe trauma can be hellishly difficult. It can involve an hours-long journey by car, fraught with danger from flying bullets and falling missiles.

On Thursday, a young pregnant woman arrived at Al-Jumhori with 60% of her body burned. Like so many who come through the hospital's doors, her home had been hit by an air strike, this one in the heavily-targeted Razeh district of Saada province, close to the border with Saudi Arabia.

With travel too risky, the woman was forced to wait for a week before her family could take her to a nearby clinic. From there she was moved by ambulance to the Al-Jumhori, a five-hour journey.

"I could not imagine how much pain she was in," said Dr Carrara. "By the time she reached us she was septic and had severe organ failure. We did what we could but there was no hope." The woman died 16 hours later. She was in her 20s.

If she had made it to Saada city within eight hours, she and her child could almost certainly have been saved.

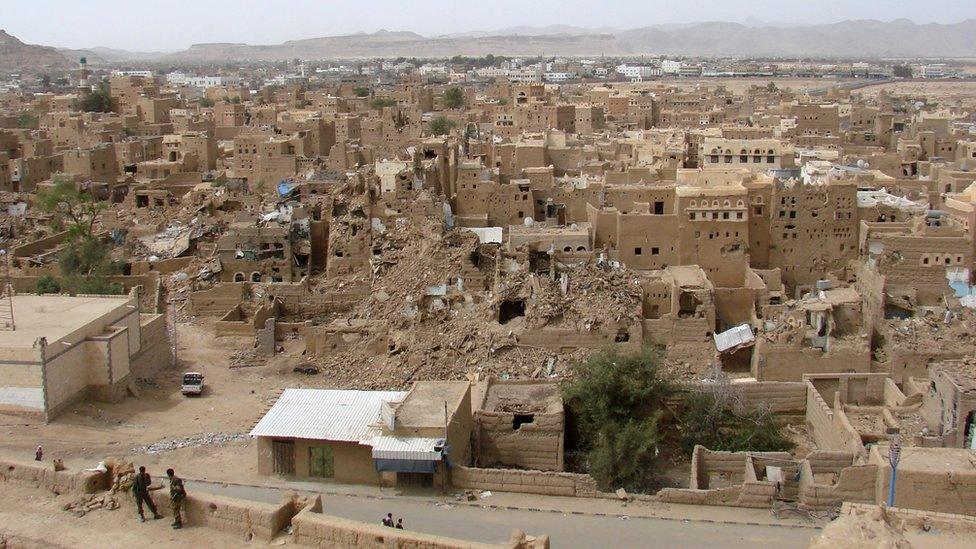

Saada, a rebel stronghold, has been pounded by air strikes since March

Patients arriving at MSF facilities in Yemen are immediately graded with one of four colours: green denotes that they are walking wounded; yellow that they must be seen within an hour; red that they need immediate resuscitation; black that they are already dead, or have no hope.

"We grade a lot of people black and red," said Dr Carrara. "Most of them are young. They have crash injuries, vascular injuries, fractures, open fractures on the legs and arms, head trauma, penetrating head trauma, abdominal trauma, chest trauma, open chest trauma, blunt trauma.

"Air strikes cause multiple, severe injuries. They put people in critical condition."

The first day we spoke, a family of seven was rushed in to Dr Carrara's A&E. Five — the mother, father, and three children — were immediately graded black. Two boys were alive. The older of the two, aged 20, was graded green — he would survive. The younger boy, aged just eight, was graded red. He had a penetrating head trauma and was in a coma.

When we spoke again the following day, the boy's condition had deteriorated. He will probably die.

In the capital, the rebels have put up billboards showing destroyed health facilities

Emergencies are not the difficult part of treating the war-wounded, said Dr Carrara. The difficulty comes later, as she follows them through their recovery — "sometimes 10 days, sometimes a month, sometimes more".

"That is when you hear their stories, what happened to them, who they lost. That's when I wonder how they can continue. And that's when it gets difficult." At what point does it become too much? "It doesn't," she said. "You do what you have to. You do the work, that gets you through."

An average day for an MSF doctor in Yemen would be too much for most. Last year, while Saada city was being bombed daily, the medical team at Al-Jumhori — a mix of MSF staff and Yemenis — were working 16-hour days and snatching naps on a handful of shared mattresses in the basement, the risk of leaving the hospital too great.

Dr Carrara's few hours downstairs were usually interrupted by emergency calls, up to four or five per night. The warning system for an emergency is often primitive: the hospital's doors and windows vibrate. A bomb has landed nearby.

"When you feel the ground shake, you know that patients are coming," she said.

The ruins of an MSF emergency department in Shiara, hit by missiles in January

In January, a missile hit the Shiara emergency room, an MSF facility in nearby Razeh district. Six people, including three members of the medical staff, were killed and seven more severely injured. The hospital was destroyed.

MSF says it does everything in its power to identify its staff and facilities to Yemen's warring factions, but there is only so much it can do.

"The situation is very difficult, the insecurity is clear," Ms Sancristobal said. "Hospitals have to be a place where patients feel safe. We don't understand how we could have had so many attacks."

The coalition promised in January to conduct a review into the strikes on MSF facilities and set up a "hotline" with the charity. Ms Sancristobal said she did not know what the coalition meant by "hotline" — MSF has been communicating its positions since the beginning of the conflict.

"The communication is good, the results are bad," she said.

In Syria, where two hospitals suffered direct air strikes last week, MSF has been forced to take a startling and opposite tack: withholding the GPS co-ordinates of its facilities from the Syrian and Russian militaries over fears they are being deliberately targeted.

MSF paints its logo on the roofs of its facilities for the benefit of aircraft

Dr Carrara is preparing to leave Yemen. In Saada city, things are beginning to improve — it is safe enough for the medical staff to live in a house opposite the hospital, although they still do not go out, only shuttle between the two buildings.

The hospital is open again for inpatients, meaning people with chronic illnesses can again seek treatment. Women are delivering babies on the wards again, every day, and staying the night.

It does not take Dr Carrara long to recall the moment that meant the most to her. One morning last October, shortly after returning to Yemen, she arrived for her shift and noticed a woman sitting quietly in the waiting area, her face covered by a veil.

She asked a nurse what the woman was waiting for. "She's waiting for you," the nurse replied. It was the woman whose arms had been so badly wounded in May, whose four young children had died.

Just as her husband had asked, the hospital staff had done everything they could — a massive operation to close her wounds, months of dressing her arms every day under sedation because the pain was so intense. And on top of all that, treatment for the malaria she contracted during her recovery.

"What stayed with me was that she had never once complained, never," Dr Carrara said. "This woman who lost her four children, she didn't complain when she arrived, she didn't complain when she was treated, she didn't complain during her recovery. Her bravery... I couldn't understand how."

That morning, in the waiting area at the hospital, she was alive and well. She had lost three fingers but only a small amount of movement in her arms. She was managing her daily activities, she said. She was coping. It was more than the doctors who had stood with her on the same spot six months before could have hoped.

Dr Carrara has an understated way of describing things — perhaps it is just the effort of using a second language — but her voice thickens a little with emotion as she remembers.

"It was difficult to talk, I don't speak Arabic. The nurse translated for us. She had come to say thank-you. It was nice. It was so nice."