Iran elections highlight deep divisions

- Published

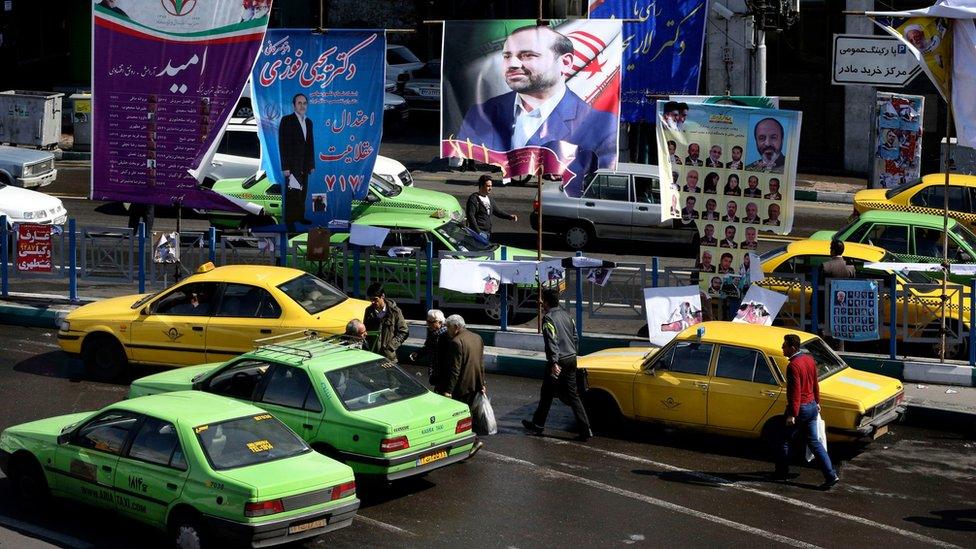

So far the election campaign has been low-key, and has not generated a lot of public debate

Iranians will vote on Friday in elections for their country's parliament and the Assembly of Experts, a clerical body that appoints the supreme leader. BBC Persian's Ali Hamedani has been talking to prospective voters via social media and offers this assessment of the mood.

It is late at night in northern Tehran and Amir, a journalist, and his wife have just been stopped by the morality police, the mobile squads that enforce Iran's strict Islamic dress code.

They were on their way home from a party when they were pulled over because the morality police believed the headscarf Amir's wife was wearing did not cover enough of her hair.

It is an everyday occurrence in Iran and just one small example of the deep divisions within Iranian society between the people who want to uphold and protect the values of the Islamic revolution, and those who are challenging it and want Iran to modernise.

Reformists are aiming to gain influence in parliament and the Assembly of Experts

It is a struggle which is dominating this week's elections.

"In previous years when it came close to an election, the government was easier on us," says Amir.

"It was a good opportunity to be freer for a few months. They didn't arrest people for their appearance, because they wanted to make people happy and encourage them to vote. But it's not like that this time."

Amir and many young, Western-oriented internet-savvy Iranians like him are disappointed that so many moderate and reformist candidates have been barred from standing in the elections.

He describes the choice facing voters as between "the bad and the worse".

But like many Iranians he still thinks the elections are a chance to make a difference.

"My friends may not vote because there is no one left to vote for," he says. "But I still think we should vote."

'I don't care'

But not everyone agrees. Justina is a rapper and in a country where women are not allowed to sing in public she is really pushing the boundaries with her hard-hitting songs about women's rights.

The elections are the first in Iran since the nuclear deal and the lifting of sanctions

"To be honest with you, I don't care about this election," she says during a recording session for her new album at an underground recording studio in Tehran.

"There are no candidates who support my hopes and opinions at all. None of them represent my voice."

If Justina is the face of young, modern Iran, then Jafar Shojouni is very much the face of the establishment.

A hardline cleric and former MP, he spent time with Ayatollah Khomeini, the founding father of the Islamic Republic, during his exile in Paris in the 1970s.

"Islam asks people to support the Islamic government," he says. "It's not about whom you want to vote for - it is about the act of voting itself."

Like many conservatives, Mr Shojouni is deeply worried that the nuclear deal between Iran and world powers, which was implemented in January, will open up the country to outside influences which could threaten the future of the revolution.

Conservatives have warned voters the West is plotting to influence the elections

"Some people think that after the nuclear deal they can return Iran back to days of the shah. No! It's not going to be like that."

Time to hope

A key issue in this issue is the economy. With sanctions lifted and Western investors beginning to return to Iran, there are high hopes for an improvement in daily life.

This is especially so in Abadan, the capital of Iran's oil industry, which is now a rundown shadow of the prosperous city it used to be.

Nima, in his 30s, wakes up every morning to the sound of oil refinery whistle. He has a post-graduate degree in engineering but, like many in the city, he has not been able to find a job.

"We don't have money to pave the city's roads," he says. "Schools don't have money to buy heaters."

Iran has a young population keen to improve their economic situation

"My friends and I will vote for somebody with good ideas on the economy, someone who can rebuild the city and create jobs."

But not everyone is so downbeat. Off Iran's Gulf coast is Kish island, once a favourite haunt of Hollywood A-listers and still a popular place for Iranians to go on holiday.

Babak and Arash both work in the tourism industry, and at a late night beach barbecue they say they are hoping business and the economy in general will pick up.

"During the sanctions tourism was not in a good condition," says Arash. "But in the post-sanctions era we're hoping it will get better. Iran is a wonderful country for tourists but everything depends on the political situation."

Babak is more cautious.

"Some people think you can change many things by voting but I don't think so!" he says. "But I still hope for better days."

- Published24 February 2016