What has happened to al-Qaeda?

- Published

Soldiers stand guard on the beach after the attack in Grand Bassam, Ivory Coast, in which 18 people were killed

A deadly al-Qaeda attack on an Ivory Coast resort town in March reminded the world that the terror network once led by Osama Bin Laden has not gone away.

But in recent years it has been eclipsed and diminished by the so-called Islamic State group which has attracted global attention, fighters and funds.

So how depleted is the group which in 2001 triggered America's "global war on terror"?

Four experts talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme.

Rahimullah Yusufzai: Rise and fall

Rahimullah Yusufzai is the editor of an English daily in Peshawar.

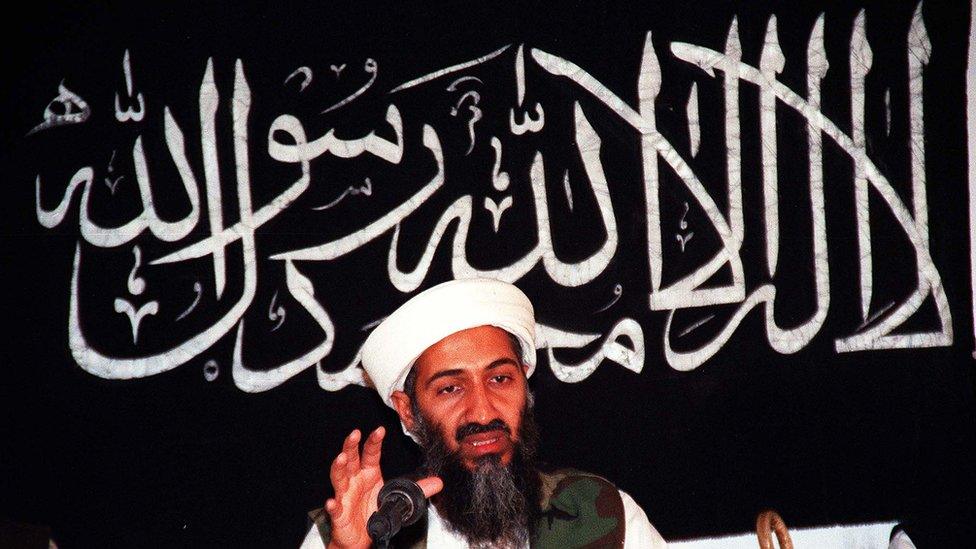

"Because of his education, his travels, his access to modern education and media, Osama Bin Laden knew about the world, about politics, and that's why he was a very charismatic leader for al-Qaeda. Before him, the others were fighting separately, but he brought them together, and then tried to build a coalition against the US and the Western world.

"Al-Qaeda used to say it was the first real jihad - or holy war - after decades, and that's why people flocked to [its training camps in Afghanistan].

"They thought this is the best opportunity to fight jihad and to get trained in modern warfare. They trained thousands. These people eventually became the torch-bearers of jihad in the rest of the world.

The death of Osama Bin Laden was extremely damaging to al-Qaeda

"In August 1998, the US attacked the same camp where I had met Osama Bin Laden in May 1998 because the US embassies [in Tanzania and Kenya] had been attacked. So the Americans were already trying to kill or capture him.

"Then after the 9/11 attacks, the US invaded Afghanistan, with the idea of destroying al-Qaeda, and removing the Taliban from power, because the Taliban had harboured Bin Laden. The Taliban were defeated in a few weeks - they had no answer to the American air power - but did not suffer many casualties. They just retreated, and melted away in the villages.

"When the Americans invaded, al-Qaeda decided to go to Tora Bora on the border with Pakistan. The Americans came to know Bin Laden was there in December 2001, and bombed heavily. I was told it was the heaviest bombing since World War Two on one target.

"Bin Laden was able to escape with the help of local Afghans, and came to Pakistan. When they attacked Tora Bora, the Americans were pushing Pakistan to block the border, to deploy a force. Pakistan actually co-operated, and for the first time deployed its troops on the borders.

"Then they launched bigger military action, because the militants were then everywhere. One of the biggest achievements is that the militants lost their strongholds. They were in control of many areas - Swat, Bajaur, Momon, South Waziristan, North Waziristan. They lost almost all these areas.

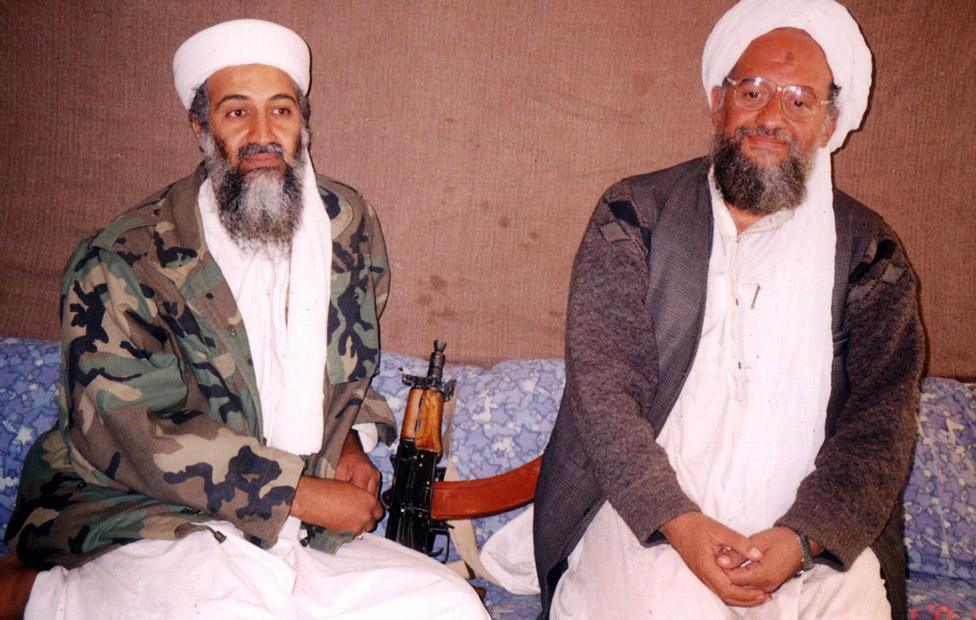

"But I think the death of Osama Bin Laden was the biggest setback, because he was the founder, the financier, the inspiration. It has never really recovered from that loss, because the new leader Dr Zawahiri is not as important, and does not have that status or authority which Bin Laden had."

Professor Fawaz Gerges: The splintering

Professor Fawaz Gerges teaches at the London School of Economics and is a prolific writer about Jihadi groups.

"Al-Qaeda has always been a top-down elitist movement. Decisions were made from the top and everyone followed. But once al-Qaeda dispersed after the American-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, al-Qaeda fractured, decentralised. The various elements spread near and far into Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Iran and then Northern Iraq.

"[In Iraq] Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was obsessed with the Shi'ites as a dagger in the heart of Iraq and the Muslim world, plunging Iraq into all-out civil war between the Sunnis and the Shi'ites, carrying out thousands of suicide bombings against the Shi'ites.

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was killed by a US strike in June 2006

"Bin Laden and his second-in-command Zawahiri tried to rein Zarqawi in many times. We have several letters of Bin Laden urging him to stop the bloodshed against the Shi'ites, to keep the focus on the far enemy, the Americans: 'don't lose the fight in Iraq'.

"Zarqawi ignored their pleas. He became the central focus of the young men and women who wanted to join al-Qaeda. In many ways, al-Qaeda in Iraq overshadowed al-Qaeda central. He became the real action man who could deliver death and vengeance against the enemies.

"Many Sunnis realised - belatedly - that Zarqawi was not their friend. He was their enemy because he had his own agenda. The Americans did not defeat al-Qaeda in Iraq: it was the Sunnis who revolted against him. Many fighters went underground, were killed.

"But a core of al-Qaeda in Iraq survived, and bade its time waiting for the right opportunity to strike back. This came in 2010.

"2010 was a very critical period because of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. He reconstructed both the military and the operational structure of al-Qaeda in Iraq to bring in hundreds of skilled officers of the former army and police of Saddam Hussein. It became the Islamic State of Iraq.

"[When Islamic State captured Mosul in 2014 and declared a Caliphate] it was a shattering blow to al-Qaeda central. In many ways the Isis (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) takeover of Mosul was really the takeover of the global jihadist movement. Isis was not just going for the Islamic state. It was also making a bid for the leadership of the global jihadist movement. They have stolen the show."

Charles Lister: Under the skin

Charles Lister is a fellow at the Middle East Institute, a US think tank, and over the past two years has had regular meetings with the leaders of over 100 Syrian armed opposition groups.

"Al-Qaeda has adapted to playing a long game strategy in which the focus has become more on building alliances and socialising local communities into being a long-term and durable base from which it can eventually launch its more trans-national objectives.

"It was a reassessment of al-Qaeda's PR strategy, the way it seeks to present itself to local populations from within which it operates, and a lot of lessons were learned from Iraq.

"In his guidelines for jihad, Zawahiri was extremely keen to send a message that instead of [killing civilians], we should fight the fight that the civilians themselves want to fight. That means military targets, security targets, not public markets or mosques, which al-Qaeda's affiliates in Iraq had previously been doing.

"In the winter of 2012/2013, [al-Qaeda's Syrian branch] Jabhat al-Nusra began to present itself not just as an armed movement, but also a social one.

Jabhat al-Nusra fighters help a wounded man following a reported barrel bomb attack by government forces in Aleppo in 2014

"It took over the management of bakeries, and forced their owners to charge a lower price. Jabhat al-Nusra was directly involved in trucking and delivering gas, bread, water and other staple food supplies to the civilian population at a far cheaper price than had been available before, and it was at that period that we started to see Jabhat al-Nusra actually gain support.

"There was a series of interesting letters found in Mali in a building that had been controlled by al-Qaeda and the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). One was from AQIM overall leader Abou Mossab Abdelwadoud in which he instructed his fighters to pull back from the extreme measures they had been trying to impose on the people.

"He was essentially describing Mali to his fighters as a baby, saying 'Your focus right now should be on teaching it the basics, raising it to be a true Muslim, and only years from now will you then be able to introduce the more harsh norms because the people will understand what is expected of them.'

"We are seeing that replication of the long game model in Yemen with extraordinarily successful consequences so far. It's no surprise that we don't hear about this very much in the news anymore: it has become almost impossible to differentiate who is al-Qaeda and who is a tribal fighter in southern Yemen.

"This new strategy makes al-Qaeda more dangerous. It shows that al-Qaeda is willing to be pragmatic, to cut back some of its religious expectations for the sake of building popular support that will gain it strength in the long term. That is something that Isis has essentially refused to do, and that means that we face that much more of a challenge of rooting it out of these societies.

"My fear is in the long term, al-Qaeda is going to be that much more durable, and the threat that they will pose will be the same as they posed in the period immediately prior to 9/11."

Katherine Zimmerman: A durable threat

Katherine Zimmerman is a research fellow at the conservative US think tank the American Enterprise Institute.

"Al-Qaeda is much stronger than people realise.

"The al-Qaeda donors haven't changed that much over the years - very conservative sheiks, particularly in the Gulf - but when you look at how al-Qaeda makes money and runs day to day as an organisation, it's less based on donations and more based on the fact that it controls terrain on the ground and taxes directly the population or benefits from trade imports, exports, etc.

"So it's very hard to isolate al-Qaeda's finances and prevent it from funding itself as long as it controls terrain.

The power previously held by Bin Laden and Zawahiri has fragmented among affiliate groups

"The hierarchy is no longer contained in a single geographical space but dispersed throughout the affiliated groups. The al-Qaeda affiliates are really no less dangerous than the al-Qaeda core group that we think about. They all have that same capability to conduct an attack.

"Al-Zawahiri certainly doesn't have the charisma that Osama Bin Laden had and that has been the main critique against him. But we've seen al-Qaeda start to shape and build up new leadership, and these include leaders in Yemen and in Syria in particular.

"[Yemen-based Saudi militant Ibrahim al-Asiri] is a bomb expert and he has an incredibly innovative mind. The man has trained other individuals and he's the mind behind the underwear bomb, the bombs disguised as printer cartridges and various other plots where they escaped intelligence agency's detection because of how well these bombs were designed. He's certainly a threat in terms of being able to bring a capability to the table for al-Qaeda.

"We are in danger of underestimating and frankly missing the threat. The real risk we face is fighting Isis and ignoring the presence of al-Qaeda. The Islamic State has seized control of vast swathes of land but it controls the population through coercion.

"Al-Qaeda doesn't control the population. It has the support of it. That's much, much more difficult to counter."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published4 April 2016

- Published3 April 2016

- Published24 March 2016

- Published23 March 2016