Israel-Palestinian tensions return to boiling point

- Published

A suicide attack on a bus in Jerusalem in April wounded 20 people

In the week or so I have been back in Jerusalem, a few people have asked me what it is I am here to cover. I thought it should be obvious.

The violence. Repeated attacks on Israelis by Palestinians, and the response by Israeli security forces.

But I have had quite a few bemused shrugs from journalist colleagues. Why now, when it has been going on since last October?

I was in Jerusalem last autumn reporting on it. What has changed? The longer something goes on the more it tends to slip down the news agenda.

But the point is that violence that becomes part of the scenery is just as dangerous as when first it grabs headlines.

It makes the deadly atmosphere between Israelis and Palestinians even more toxic. The attacks have become almost routine. Except for those who are caught up in them.

Mutual hatred

Eden Dadon, a 15-year-old Israeli girl, is in hospital in Jerusalem with 45% burns that she suffered when a Palestinian set off a bomb on a bus on 18 April.

When I met her mother, Rachel, at the hospital, Eden had been on a ventilator in an induced coma for more than a month.

The doctors were trying, slowly, to wake her, Rachel said, but it was difficult because her daughter was in great pain and had developed pneumonia.

A bomb on a bus revived horrible memories for Israelis of the attacks that killed hundreds of people during the second intifada (Palestinian uprising) in the years after 2000.

Rachel Dadon's daughter Eden suffered 45% burns in the Jerusalem bus bombing

Rachel, who was scared before the bus she and her daughter boarded blew up, is a single mother. She has had to stop working as a carer for old people so she can spend time with her daughter.

Looking down on the bandages still covering the wounds she suffered in the explosion, Rachel complained that no-one from the government or the Jerusalem Mayor's office had been in touch.

The trauma left by the attack is in her mind constantly.

"We are civilians of the state of Israel that don't need to live like this. To be afraid to go by bus, to be afraid to get on a train, to be afraid to speak to people. Today everyone is suspicious. You don't know who's OK, and who isn't."

Rachel's older daughter, Shiran, was with her at the hospital. I asked her what she thinks when she sees a Palestinian walking down the street.

"I think why are they so evil? Why are they so bad? Why can't we live in peace… these are wars that we have been living with for many years and we'll never find a resolution to this because they hate us.

"Of course. And we hate them… the difference between us is that they are the ones that come to attack."

Rising anger

As always, the view on the Palestinian side is very different.

I travelled a few miles from Jerusalem to Beit Jala, a small town next to Bethlehem, to the home of Abdul Hamid Abu Srour, 19-year-old Palestinian who blew up the bus in Jerusalem with such horrific consequences for Rachel Dadon and her family.

He was badly hurt in the blast, and died a few days later.

The Abu Srour family are not friends of Israel. Two of Abdul's uncles are serving long sentences for killing an Israeli intelligence agent. His cousin was shot dead in a clash with Israeli troops three months ago.

Azar Abu Srour's son blew up the bus in Jerusalem that wounded Eden Dadon and 19 others.

The Abu Srour family support a secular left-wing Palestinian faction called the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP).

It carried out deadly attacks on Israelis in the 1970s, but later it joined peace talks and in 1999 was dropped by the United States from its list of terrorist organisations.

Abdul's attack, though, was claimed by Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement.

Azar Abu Srour, Abdul's mother, grew up as a Palestinian refugee in Syria. Now she teaches Arabic in a Christian school.

Her father was killed in an Israeli air strike in Lebanon in 1981. Azar had dark, grief-stricken circles under her eyes. But said she was proud that her son had chosen what she called "the resistance".

"Not just Abed [Abdul], I think all the people here now prefer the resistance. Because for them peace is a hopeless case."

"He was angry for everything that happened in Palestine. He was watching what happened everyday. Killings, arrests, destroying homes, everything. Of course he was angry."

Core of the conflict

On both sides of Israel's separation barrier in and around the occupied West Bank at best there is cynicism about the future. At worst there is mutual hatred.

The Israeli prime minister's spokesman told me that "teaching Palestinian children to hate is one of the primary causes of the terror attacks against Israeli civilians today… their impressionable minds should not be poisoned with hatred by the Palestinian Authority."

Hate-filled Palestinian rhetoric against Israel is not hard to find. It cuts the other way too.

Fans of one of Jerusalem's professional football clubs, which has roots in a right-wing Zionist youth movement, are notorious for chanting "Death to Arabs" during games.

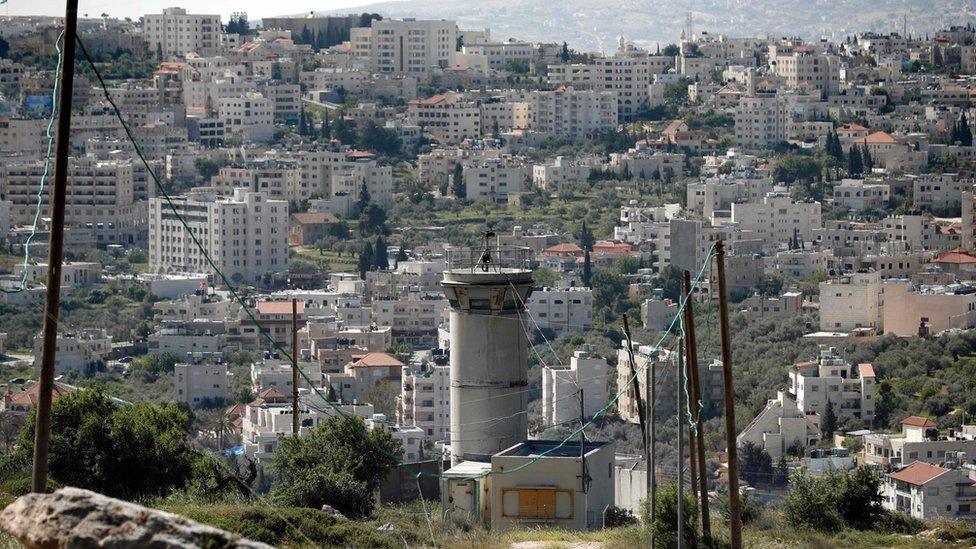

This picture taken from a settlement in east Jerusalem shows an Israeli army watchtower overlooking the Palestinian town of Beit Jala

But hundreds of conversations with Palestinians over many years here have convinced me that the biggest factor that shapes their attitudes to Israel is not the incitement to hate but the occupation of the Palestinian territories, including East Jerusalem, that started after Israel's victory in the 1967 Middle East war.

When Palestinians who agitate against Israel find an audience, it is because of the way that the occupation, which is inherently violent, has overshadowed and controlled Palestinian lives for almost 50 years.

The issues here do not change much. Two peoples have been fighting for generations about one piece of land. That is still the core of the conflict.

Twenty-five years of peace talks have failed. The current violence is scaring off tourists and pilgrims but as ever Israelis and Palestinians are living their lives around it.

That is no kind of status quo. Israelis fear and hate the attacks. Palestinians hate the occupation and loathe what they say is Israel's trigger-happy response to threats, often complaining that they are scared to reach into their pockets or bags near Israelis soldiers and police officers in case they get shot dead.

Volatile atmosphere

Alongside the attacks on the streets, the big issues that can cause international crises continue to simmer.

One of the most potent is the tension over Jewish access to the compound containing the al-Aqsa Mosque. The hilltop its on is also the holiest site in Judaism.

Tension is rising on Israel's borders with Gaza too. Peace talks are dead and no-one is trying to revive them.

The result is that the atmosphere in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, is more combustible than it has been since the end of the second Palestinian uprising more than a decade ago.

History has shown that neither side has the beating of the other. One day they might be able to make a peace deal.

If not they face the slow drip of hate and certainty of more killing.