Syria war: Battling on as a disabled refugee

- Published

What does the future hold for disabled refugees in Jordan?

Of the estimated 1.4m Syrians who have found safety in Jordan, about a third have a disability or serious health condition.

That's a lot, but in many ways it's expected. War leaves its mark. The country has taken in so many refugees it's overwhelmed.

The Jordanian government admits it's unable to support everyone. Put simply, in order to comprehensively support refugees who need more than the very basic level of care, they need more money.

Before we made this film, Our World: Displaced & Disabled, I couldn't quite understand how you escape when you have a disability and, if you manage to, what happens if you require essential rehabilitation or ongoing treatment in order to maintain what little independence you have?

A huge number of refugees arrive in Jordan with some form of disability

Prosthetic legs are not cheap. Physiotherapy is a luxury for many. Medicines are expensive. Wheelchairs break and cost money to repair.

For me to make this documentary in a more challenging environment for someone with a physical disability, I had a producer who planned the entire trip, making sure there was a van that I could get in and a wonderful driver who parked in easy spots - a strong man who lifted my scooter and me in and out the van several times a day.

Even with access to a ramp and wheelchair, there were still places and people I couldn't get to.

The people I met don't have this kind of support but that makes them tougher, more resilient. Many know their strengths and they want to show the world that they are capable of doing anything, despite their situation.

Psychological support

Together with Handicap International, one of the main charities working on the ground, we visited Jordan's two Syrian refugee camps - Zaatari and Azraq.

Zaatari is only a few miles from the Syrian border; it is a city in the middle of a desert, packed with close to 80,000 refugees.

In Azraq, people have to walk miles to get basic supplies - very difficult for those with a disability

At one of the charity's fixed meeting points in Zaatari, I remember thinking I'd not seen that many amputees in one place.

These are the people having to deal with the ramifications of war but, at the meeting point, they are able to receive vital support from highly trained and dedicated staff.

I met men who had lost limbs, walking "the bars" - something most people with a physical disability have had to do at one time or another - which support you while you take a few tentative steps. It's great exercise.

Nikki Fox meets disabled refugee Ragda

Mohammed, who has cerebral palsy, was playing games to improve his stability. Ragda was doing her arm exercises to keep strong - she's got a wheelchair to push, provided by the charity, something she didn't have back home in Syria.

There's also crucial psychological support, something I imagine most people forced from their homes and loved ones could do with.

Sense of humour

Zaatari was the first refugee camp I'd visited, and I'd built up this picture in my head, pieced together from various news reports and online articles.

There's no getting away from it; life as a refugee is tough, too tough for many to comprehend. The basics we take for granted are not freely available here and, when you have a disability, it can make life almost impossible.

Children at the camp follow Nikki Fox in her mobility scooter

But what I wasn't as prepared for was the spirit and strength of the people existing in the camp - their life in limbo.

When you have a disability, you don't want people to feel sorry for you; you just want to get on with things.

That was certainly the case with many of the disabled Syrians we met. They know their situation is dire, but they still laugh, they had fun with us over lunch, they enjoy a cigarette and a few jokes. I have never been asked if I'm on Facebook quite as much.

Priced out

But not all Syrian refugees live in the camps. Around 80% of all the refugees in Jordan live in and around the main cities, like Abd al-Aseem and his brother, who live in Jordan's capital, Amman.

Abd had a stroke. For months he couldn't walk, he couldn't move. He needs expensive medication the family just can't afford.

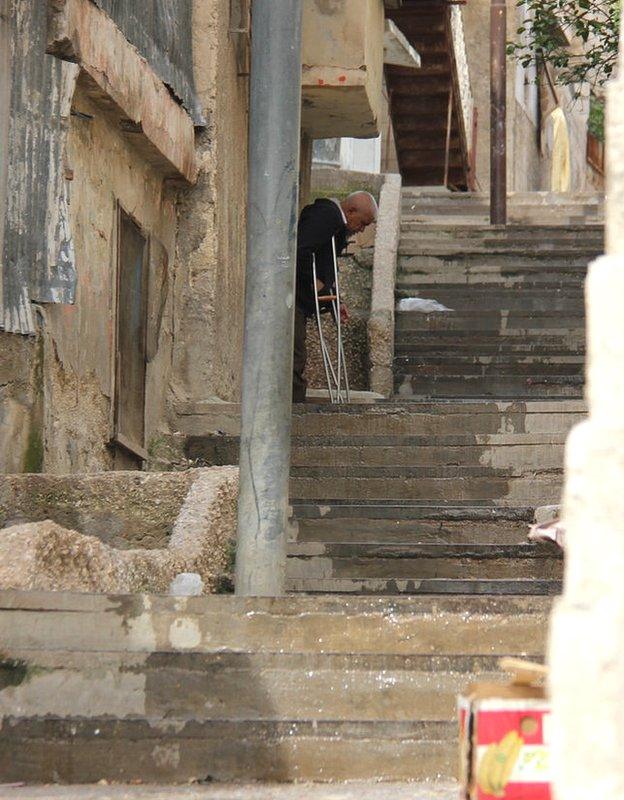

Life with a disability can be difficult in Amman, colloquially known as the City of Stairs

They owe money and, although he is slowly improving thanks to the dedication of his family and support from a charity, he still needs to be carried from the third floor in order to leave his apartment.

A big problem for disabled refugees is the price of apartments like Abd's. The higher the floor, the cheaper the rent.

Abd is still unable to speak but his brother told me he was a kind, generous man who ran his family business and had time for everyone who needed him.

He had previously had a nice life and could provide for his wife and kids. Now, his situation is bleak; life has dealt him a rubbish hand. The family can't dream of returning to Syria, they just have to get through each day.

'Lazy girl'

But, for one young man, all he wants is to go back home. I met the charismatic Moead at a hospital for reconstructive surgery, run by the charity Medecins Sans Frontieres, in Amman.

Moead is having reconstructive surgery after losing a leg in a blast in Syria

He lost one of his legs in an explosion in Syria. We got on straight away. He liked my mobility scooter, I told him it would make him lazy, and for the rest of the time we spent together he called me "lazy girl". I was calling this flirting, but I think that's a stretch.

I met so many incredible people whilst making Our World: Displaced & Disabled, all very different but with one thing in common - a total reliance on charity to get by, and that's scary.

We all like to think we're in control of our own lives, but the people I met are not.

Our World: Disabled & Displaced will air on BBC World News at the following times:

Friday 27 May at 21:30 GMT

Saturday 28 May at 11:30 GMT

Sunday 29 May at 04:30 and 17:30 GMT

Friday 3 June at 09:30 GMT