Dead Sea drying: A new low-point for Earth

- Published

The surface level of the Dead Sea is falling by more than a metre a year

The Dead Sea, the salty lake located at the lowest point on Earth, is gradually shrinking under the heat of the Middle Eastern sun. For those who live on its shores it's a slow-motion crisis - but finding extra water to sustain the sea will be a huge challenge.

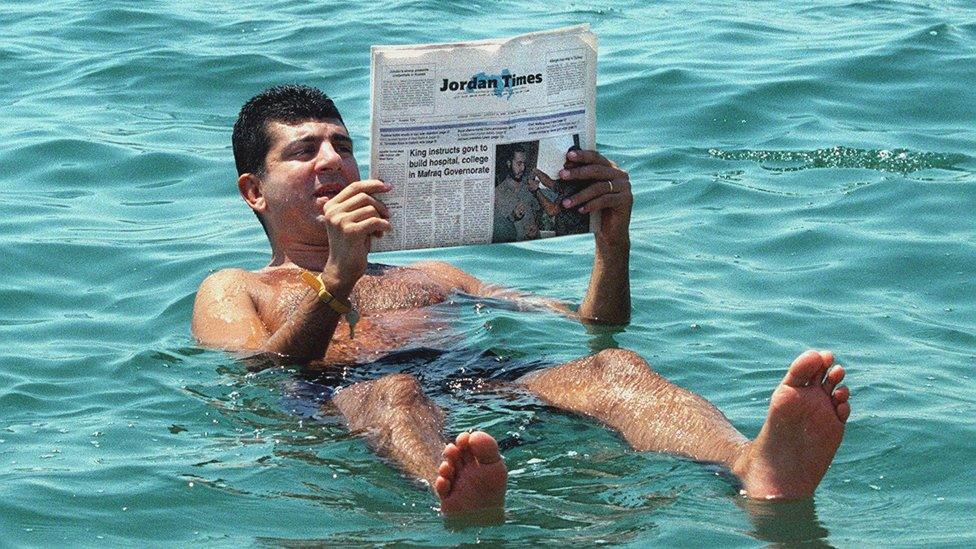

If there's one thing everyone knows about the Dead Sea it is that you can't sink in it.

It is eight or nine times saltier than the oceans of the world - so dense and mineral rich that it doesn't even feel like normal water, more like olive oil mixed with sand.

For decades no holiday in the Holy Land or Jordan has been complete without a photograph of the bather sitting bolt upright on the surface, usually reading a newspaper to emphasise the extraordinary properties of the water.

But the Dead Sea is also a unique ecosystem and a sensitive barometer of the state of the environment in a part of the world where an arid climate and the need to irrigate farms combine to create a permanent shortage of water.

The Dead Sea is so rich in salt and other minerals that humans float naturally on the surface

You may have read that the Dead Sea is dying. You can see why the idea appeals to headline writers but it isn't quite true.

As the level drops, the density and saltiness are rising and will eventually reach a point where the rate of evaporation will reach a kind of equilibrium. So it might get a lot smaller, but it won't disappear entirely.

It is however shrinking at an alarming rate - the surface level is dropping more than a metre (3ft) a year.

When you consider that the surface of the Dead Sea is the lowest point on the planet - currently 420m (1,380ft) below sea level - that means that the planet's lowest point is being recalibrated on an annual basis.

It is deep enough that journeying along the road that winds down to the shore causes your ears to pop as they do on an aircraft coming in to land.

The landscapes of the Dead Sea have an extraordinary, almost lunar quality to them - imagine the Grand Canyon with Lake Como nestling in its depths. And the people of the ancient world understood that there was something unique in the place, even if they couldn't be quite sure what it was.

A BBC drone provides a unique look at the buildings that have been abandoned as the Dead Sea has retreated and sinkholes have emerged

The story goes that Cleopatra used products from the area as part of her beauty regime, which as everyone knows also allegedly included asses' milk and almond extract - although in truth tales like that are ten-a-penny around the Middle East.

And it's possible that King Herod, who had a winter palace nearby, came here for his health too - although his tarnished historical reputation does tend to devalue his worth as a celebrity endorser in the classical world.

What is certain is that when the Romans occupied the Middle East they exerted rigid military control over the roads around the Dead Sea because it was such a fertile source of salt - a commodity so valuable then that it was used as a form of currency.

And the health benefits appear to be real enough. The intense barometric pressure so far below sea level may produce atmospheric conditions beneficial for asthmatics - I am a sufferer and I noticed a degree of difference.

And people with the painful skin disease psoriasis also seem to find relief in the combination of mineral-rich water, soothing mud and intense sunlight. In some countries, health agencies and charities pay for people with the condition to come on therapeutic trips.

So even though the Dead Sea is shrinking and changing, it still has an economic value. Tourists can choose to visit resorts in either Jordan or Israel and both countries also export cosmetic products manufactured in the area.

Part of the shoreline is in the West Bank under Israeli occupation so it's possible that in future Palestinians too will reap the economic benefits of the sea's unique properties.

The area around the sea has an established tourism and health industry because of the water's unique properties

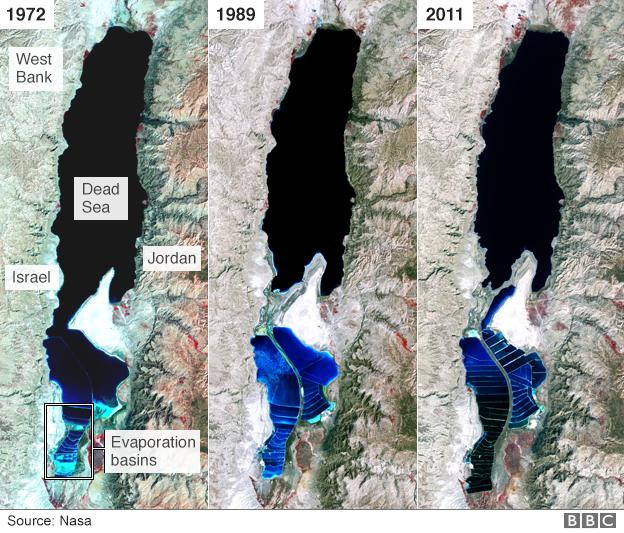

But there's no doubt that the decline in the water level has been spectacular.

During the World War One, British engineers scratched initials on a rock to mark the level of the water. A century on, those scratch-marks are high on a bone-dry rock.

To reach the current water level you must climb down the rocks, cross a busy main road, make your way through a thicket of marshy plants and trek across a yawning mud flat. It's about 2km (1.25 miles) in all.

A few kilometres along the coastline, in the tourist resort of Ein Gedi, the retreating of the water has created a huge problem.

When the main building, with its restaurant, shower block and souvenir shop, was built towards the end of the 1980s, the waves lapped up against the walls.

Now the resort has had to buy a special train in which tourists are towed down to the water's edge by a tractor (another 2km journey).

For Nir Vanger, who runs the business side of Ein Gedi's tourist operations, it's an unnerving rate of change.

"The sea was right here when I was 18 years old, so it's not like we're talking about 500 or a 1000 years ago," he says. "The Dead Sea was here and now it's 2km away, and with the tractor and the gasoline and the staff it costs us $500,000 a year to chase the sea.

"I grew up here on the Dead Sea - all my life is here, and unfortunately in the last few years that's a bit of a sad life because you see your home landscape going and disappearing, and you know that what you leave for your children and grandchildren won't be what you grew up with.

"When we built a new house my wife asked me if I wanted a view of the sea and I said we should build it with a view of the mountains because they stay where they are and the sea keeps moving.'

Kevin Connolly looks at how the disappearing Dead Sea is affecting the tourism industry

So it's not hard to understand the mystique of the Dead Sea, with its unique chemistry, harsh micro-climate and soaring camel-coloured mountains - a landscape that would still be recognisable to Herod and Cleopatra, give or take the odd multi-storey concrete hotel.

But to a geologist it is simply the terminal lake of the River Jordan - its end point. The river flows in at one end but the water doesn't flow out again at the other - it just sits there and evaporates.

And while it is an exaggeration to say that the Dead Sea is dying, that would be a reasonable description of the river that feeds it.

It's true that in the brief rainy season there are flash floods that bring water coursing through the wadis, or stony inlets. But these are parched for most of the year, and the river itself barely more than a trickle.

There are places in Israel and in the occupied West Bank where, in the dry season, you can almost step over it.

The Jordan was once one of the great waterways of the ancient world - Christ was baptised in it - and even in relatively modern times it was a surging river prone to flooding in rainy winters.

The Dead Sea borders Israel, Jordan and the West Bank and is fed by the River Jordan

In 1847, the US government despatched a naval expedition to explore the Jordan for motives that appear to have been as much religious as they were scientific or navigational.

The expedition was led by a doughty officer called William F Lynch, who deserves a footnote in the history of the region if only because he may have been the first person to calculate that the Dead Sea lies below sea level.

Lynch's description of his adventures is entertaining, even if he has a habit of describing the indigenous peoples of the region in ways that grate on 21st Century sensibilities.

What's interesting is his description of the river itself, where at one point he finds a series of 5m-high waterfalls separated by rapids - he even fears that he'll lose one or more of the expedition's boats.

"We halted at the ruins of an old bridge now forming obstructions over which the foaming river rushed like a mountain torrent," he writes. "The river was 30 yards wide."

Eighty years or so later, there was still enough water in the Jordan to allow a Russian Zionist engineer called Pinchas Rutenberg to construct a hydro-electric power station in a remote stretch of the river valley - its abandoned buildings still stand there in what is now a desiccated landscape.

The ruins of the Naharayim hydro-electric power plant that was built by Pinchas Rutenberg

Things are startling different these days.

The geography of the region hasn't changed, of course. The northern section of the Jordan flows into the Sea of Galilee and then the southern section flows south out of the Galilee and down into the Dead Sea.

But the amounts of water flowing into and out of that system have changed spectacularly in recent decades - all part of the complicated politics of water in the Middle East.

Israel has a dam across the southern section of the Sea of Galilee which gives it control of the amount of water flowing into the Jordan - it regards the Galilee as a vital strategic water asset, even though it's been steadily increasing the amount of fresh water it creates through desalination plants in the Mediterranean.

The Israeli government began taking water out of the Jordan Valley system in the 1950s, the decade before it completed the dam.

And this creates problems for farmers in both Jordan and the Palestinian territory of the West Bank - all of whom need water to irrigate their farms and feed their people.

But Israel has problems too - although it has enough money and enough technical resources to ensure its own people have enough water.

The River Jordan is fed by the River Yarmouk, which flows through Syria. Over the last 30 years or so, the Syrians have built more than 40 dams to harness the water in the Yarmouk - water that once fed the Jordan.

Some Jordanians believe Syria built some of these dams to punish Israel and Jordan for signing a peace treaty in 1994.

The Dead Sea has been disappearing more quickly as surrounding countries have built dams

The deal brought Jordan into line with Egypt, which signed a similar treaty in 1979, but left it badly out of step with other countries like Syria.

Others are prepared to accept that the Syrians built the dams because their own people needed water, but either way the result is the same - less water available for a once-mighty river.

And of course the Kingdom of Jordan has built dams for its own purposes too.

More broadly still, the Jordan Valley is not the only place in the Middle East where the construction of a dam has created a strategic dispute.

When Turkey built the Ataturk Dam on the Euphrates in the 1990s, Iraq and Syria complained that the vast construction project cut the flow of water to them.

There is one bright spot in this otherwise overwhelmingly gloomy regional picture.

In recent years, Israel has increased the amount of water being released in the River Jordan - the effect has only been to turn a trickle into a slightly bigger trickle, but it's better than nothing.

The bottom line is that as populations rise across the Middle East, the demand for water is rising with it - and in a region where it's almost impossible to make broad, multi-lateral political agreements, it's difficult to imagine a deal being struck to manage water more fairly, more wisely and less competitively.

There are other factors which affect the level of the Dead Sea - both Israel and Jordan use huge evaporation basins to extract valuable phosphates from the water to be exported as fertiliser - but it's the striking decline in the River Jordan which does most to explain why the Dead Sea is in crisis.

Kevin Connolly speaks to farmers on the Jordanian side of the Dead Sea

On the Jordanian shore of the sea, there is a small community of families growing tomatoes, bananas and watermelons in fields kept lush by underground supplies of fresh water, which sweep down from the surrounding mountains.

Among the farmers there is Salim al-Huwemel. Like Nir Vanger in Ein Gedi, he feels rooted in the land.

"We'll never leave," he says as the young men of the village harvest melons in the cool early evening sunset, "Even if the Dead Sea were to rise up and sweep us into a sinkhole. We will always be here."

Those sinkholes are the common enemy of villages and business on both the Jordanian and Israeli coastlines.

They form when underground salt deposits left behind by the sea as it retreats either collapse into huge chasms or dissolve when fresh water seeps underground and causes the ground above to give way.

Some of the craters are huge - perhaps 100m across and 50m deep - and in places it looks as though the area is in the grip of a powerful earthquake happening over the course of several decades.

A series of structures that have been swallowed by a sinkhole on the Mineral Beach

The Jordanian farmers showed me the ruined site of an old salt factory that collapsed into a hole.

On a section of shore that is within the West Bank, a resort has been closed because part of it was swallowed up by another sink hole.

And an Israeli filling station has closed because the road around it started to crack, split and collapse.

All in all, there are now more than 5,500 such holes around the shoreline where 40 years ago there were none.

This is somewhere where you feel geology is happening in real time. Where the sea has retreated, the salt crust beneath your feet creaks and crumbles deafeningly as though you're walking over sheets of cracked glass.

It is an exciting place to be a scientist, says Dr Gidi Baer of the Geological Survey of Israel. Dr Baer says geologists are getting better at predicting where sinkholes are going to open - which is important when you consider that there are several busy roads running around the coastline. But the problem's getting worse.

"The number's not linear," he told me. "It's growing and accelerating. This year, for example, about 700 sinkholes formed, but in previous years the number was lower. In the 1990s it was a few dozen, now it's hundreds."

Diagnosing what's wrong with the Dead Sea isn't difficult - it has after all been shrinking for at least 100 years, since those British engineers left their mark in the rock.

Deciding what, if anything, should be done about the water level is more complex - a huge scientific and political issue. Geologists make the point that the level of the water in the past has probably been both higher and lower than it is now.

The increasing number of sinkholes has made it difficult for farmers to operate safely in the area

The question is what the costs and benefits of any attempt to "save" the Dead Sea might be - whether that would be to slow the rate of decline or to do something vastly more ambitious and start to raise the level again.

"You have to ask, what we are trying to preserve here," says Dr Ittai Gavrieli, another scientist from the Geological Survey of Israel.

"Are we trying to raise the water level? To preserve the unique chemistry of the Dead Sea? And for what purpose - for tourism? If we want to restore the flow of the Jordan river, for example, then Israel would have to desalinate more water and that would cost money and have an environmental impact too."

If the Jordan were ever restored, of course, it would be impossible to expect that Palestinian and Jordanian farming communities desperate for water on either bank would simply sit back and let the water flow by in the interests of science.

But there is, of course, a case for doing something.

Salem Abdel Rahman, a Jordanian activist for the Ecopeace Middle East environmental group puts it like this: "We are not talking about saving the Dead Sea because it's nice or not nice. We think that the Dead Sea is a symptom of sickness in the management of water resources. The saving of the Dead Sea will be a good indication that we moved away from sickness to a healthy environment."

If the waters of the River Jordan are not to be restored, the likeliest scheme to revitalise the Dead Sea involves constructing a huge pipeline that would bring water across the desert from the Red Sea, far to the south.

Similar ideas have been around for long time - British engineers once contemplated constructing canals to connect the Mediterranean to the Red Sea via the Dead Sea.

It would have provided an alternative to the Suez Canal under British control, but proved impracticable because of the depth at which the Dead Sea lies below sea level.

The proposed pipeline would travel from the Dead Sea to the Red Sea across Jordan

Even by modern engineering standards, the Red-Dead project as it's known would present some formidable technical challenges.

Water would have to be desalinated first at the Red Sea (salty water would pollute the Dead Sea's unique chemistry). It would then have to be pumped up to a great height and fed into enormous pipes that would channel the water across the desert to its destination.

The extra fresh water would benefit not just Jordan and Israel but the Palestinians too, so the World Bank is keen and the US is likely to provide at least some of the start-up capital.

But the technical, financial and political difficulties are forbidding and the pipeline is unlikely to be built soon, if indeed at all.

It's possible, of course, that the countries of the Middle East will find that co-operation impossible - multilateral agreements in this part of the world are rare.

In which case, the Dead Sea will continue to shrink at something like its current rate for years to come, but it won't die.

The science of saltiness and saturation means that the Dead Sea will eventually reach a point of equilibrium where it will stop shrinking. In simple terms, the amount of water in the sea's briny cocktail and the amount of evaporated moisture in the air above it would reach a kind of balance.

And the Dead Sea has another trick up its sleeve too - it is prone to a certain level of evaporation for example but it's also hygroscopic, which means it is capable of absorbing water from the atmosphere around it. It's almost as though this endangered natural treasure has a kind of in-built safety mechanism.

The sun-loungers in Jordan and Israel alike may have to be pushed quite a bit further across the beach before we get to this point, but a minimum level will one day be reached.

So this is not in the end a story about how the Dead Sea is going to die - more an encouraging story about how nature in a region where man has not always been careful with natural resources can sometimes find a way to protect itself.

.