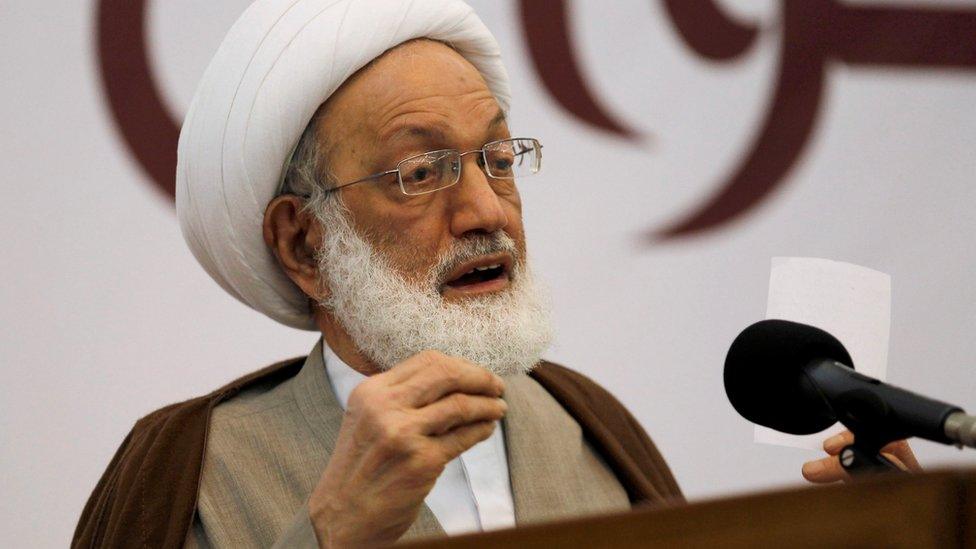

Sheikh Isa Qassim: What lies behind Bahrain's latest opposition crackdown?

- Published

Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of top Shia Muslim cleric Sheikh Isa Qassim

The story of Bahrain's 14 February uprising in 2011 can be told in four broad chapters:

Mass demonstrations and failed negotiations

A bloody government crackdown

A perfunctory attempt at reconciliation and dialogue

Political stalemate born of royal infighting and sectarian polarisation.

That stalemate arguably ended with the government's decision to revoke the citizenship of Sheikh Isa Qassim, the kingdom's most prominent Shia Muslim cleric and spiritual inspiration behind the main opposition bloc Wefaq.

The move is but the coup de grace in a series of recent crackdowns on dissent.

These included the re-arrest of outspoken government critic Nabeel Rajab and a travel ban on activists planning to attend this month's UN Human Rights Council in Geneva.

Sheikh Isa Qassim is the spiritual inspiration for Bahrain's main opposition

The government has also imposed an extended nine-year prison sentence for Wefaq's longstanding secretary-general Sheikh Ali Salman, introduced a new law barring religious leaders from membership in political societies, and has enforced the wholesale suspension of Wefaq's activities.

On the face of it, such decisions would seem to point to an emboldened regime finally willing to throw off the pretence of entertaining serious reform - one confident in its ability to handle the inevitable domestic and international fallout of redoubled political repression.

And, on the diplomatic front at least, such a conclusion is undoubtedly correct. Since Wefaq's boycott of 2014 parliamentary elections in protest at a lack of meaningful concessions by the state, its one-time interlocutors at the US and British embassies have all but shunned the group.

The UK Foreign Office in particular has communicated bluntly that the opposition made its own bed by refusing to participate within the existing political framework, however flawed, and now will have to sleep in it.

Posters for Wefaq's secretary general, Ali Salman, who has been jailed for nine years

Around the same time at the regional level, the unforeseen rise of so-called Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq meant that the US and its allies found themselves in immediate material need of Bahrain and the other Arab Gulf states, rather than the usual reverse relationship.

In return for their diplomatic and (nominal) military assistance, Gulf leaders demanded greater leeway in managing domestic politics. In the case of Bahrain, Western criticism and engagement have been noticeably muted since.

Following the Saudi strategy?

What is less clear, however, is whether Bahrain's latest measures against the opposition are evidence of a position of domestic strength, or of perceived vulnerability. At least three separate factors are at play. Notably, two of the three have more to do with economics than politics.

The first is Bahrain's Sunni Muslim community, which gave vital support to the ruling family in 2011 by organising counter-rallies that helped arrest the momentum of the uprising.

Bahrain has been wracked by unrest since a pro-democracy uprising was crushed in 2011

But rather than fading away with the end of mass demonstrations, many of these populist Sunni coalitions transformed into political movements in their own right, making demands upon the state, often vocally, for higher wages and a harsher security response to lingering protests.

Fearful that these groups could potentially give rise to a new phenomenon of Sunni opposition, the state redrew electoral boundaries in time for the 2014 elections in a way that disadvantaged their candidates, who failed to win a single seat.

These electoral machinations, combined with the government's new disqualification of religious leaders from politics, makes it clear that it is not simply Shia who are the target of the state's clampdown, but politically active Sunnis as well.

This bodes ill for the country's two largest and most established political societies after Wefaq, which represent Salafists and followers of the Muslim Brotherhood respectively. For ordinary Sunnis, such suspicion is seen as poor repayment for their loyalty in the state's hour of need.

Oil price squeeze

A second factor that could help explain the timing of Bahrain's authoritarian turn is the fiscal crisis presently facing the state as a result of low oil prices.

Low oil prices have squeezed living standards

Already poor by Gulf standards, in the past six months alone Bahrainis have had to endure a string of cost-cutting measures that have seen dramatic overnight increases in the prices of food, water and electricity, and vehicle fuel.

The state has promised even further fiscal tightening in the form of a GCC-wide value-added tax, increased fees on government services and even changes to state pension benefits.

In Saudi Arabia, similarly painful economic reforms announced in January were famously preceded by the surprise execution of dissident Shia cleric Sheikh Norm al-Nimr, which most observers interpreted as a transparent attempt at appeasing the regime's core Sunni supporters. Might Bahrain be taking a page from the Saudi playbook?

Royal manoeuvring

Finally, it is possible that Bahrain's steps toward authoritarian retrenchment reflect a struggle for influence within the fractured ruling Khalifa family itself.

Specifically, the immediacy of the country's economic challenges has thrust back into the limelight Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad, a moderate who was marginalised after an embarrassing failed attempt at negotiating with Wefaq leaders in February 2011.

Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad has been marginalised after an attempt to talk to Wefaq

The crown prince's economic reform agenda is strongly opposed by his powerful uncle, Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman, whose influence is rooted in vast patronage networks.

The bold steps against the opposition may thus be a message to the reform-minded Salman that he should not expect the newfound demand for his economic expertise to present an entry into the political realm.

Equally likely, perhaps, the experience of the past five years may have brought the Crown Prince closer to the thinking of more conservative members of his family: that engagement with the opposition is at best a waste of time, at worst a repeat of a grave mistake. And far better, then, to do away with it altogether.

Justin Gengler is Research Programme Manager at the Social and Economic Survey Research Institute of Qatar University. He is the author of Group Conflict and Political Mobilization in Bahrain and the Arab Gulf.