Iraq seeks more help as it sets sights on Mosul

- Published

Iraqi government forces recently retook the Qayara airbase, 60km (40 miles) south of Mosul

Black banners of so-called Islamic State (IS) flap in the scorching heat of northern Iraq. Fighters' corpses lie where they fell, wrapped in dust, in parched wheat fields.

An Iraqi military convoy hurtles along dirt tracks, kicking up a haze which shrouds deserted shells of houses with a ghostly pallor.

The only speck of colour on this terrain is Iraq's red, white and black tricolour raised on rooftops and tank turrets.

Village by village, battle after battle, Iraqi forces are slowly advancing towards the northern city of Mosul.

In this area, captured in recent weeks, they're now about 60km (37 miles) south of IS's de facto Iraqi capital, where the creation of an Islamic "caliphate" was proclaimed two years ago.

"Our orders are to liberate every square inch of Iraq. We are determined to eliminate Daesh [IS] by the end of the year," Iraqi army chief Lt Gen Othman al-Ghanimi tells me as we travel with him on his first visit here in the wake of their latest battlefield successes.

Donor fatigue

If this is the year of the big battle to retake Mosul, its consequence could be what United Nations envoy Jan Kubis describes as "the biggest, most sensitive humanitarian crisis in the world".

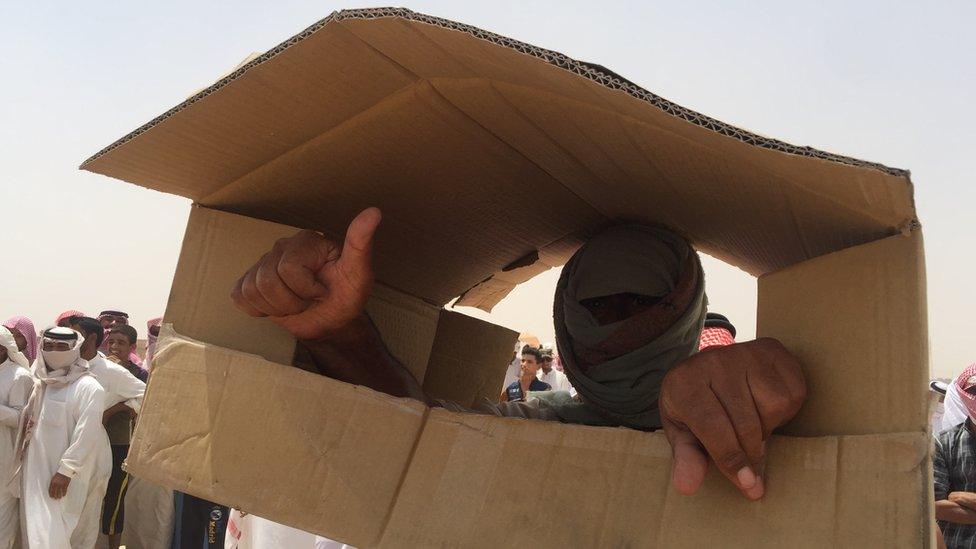

People displaced by the fighting have been arriving at camps, where food and water are scarce

As Iraqi forces inch forward, more and more families are fleeing the other way - escaping with their lives from the clutches of IS, but entering another kind of hell.

The world's aid community is already struggling to help care for almost 3.4 million people left homeless by earlier battles. This year, the UN's annual appeal is less than 40% funded.

"There's donor fatigue," says a frustrated UN official in Baghdad. "It's almost as if the world wants the Iraqi problem to go away, and they're embarrassed it's still here."

Whatever the failures which followed the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the campaign against IS is now what matters in many capitals.

The jihadist group's reach now stretches far beyond the territory it holds in Iraq and Syria.

The self-styled caliphate has been a lodestone for foreign fighters and supporters who have carried out attacks in cities worldwide.

Stuck outside in temperatures exceeding 50C, some have been improvising to create shade

The human cost in Iraq of this crucial war now seems to be registering.

At the same time as defence ministers of major military powers are assessing the battles ahead at a meeting in Washington of the Global Coalition to Counter IS, major donors are also gathering there to find more funds for a looming humanitarian crisis.

"You can't have one meeting without the other," insists Peter Hawkins, the Iraq representative of the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef). "This will be biggest thing in 2016 in terms of human cost. There's no question about that."

The hope is to reach pledges totalling almost $2bn (£1.5bn) for operations linked to the Mosul campaign, but also $284m (£215m) to prepare for it.

'No food, electricity or water'

On the ground, the cost mounts by the day.

On the edges of the northern city of Tikrit, which was recaptured from IS by Iraqi government forces in March 2015, hundreds of families converge on rocky ground in a desperate search for aid of any kind.

Most have fled, with only the clothes they wore, from fighting on a new frontline in the town of Sharqat, about 100km away.

Ali Shimmari is grateful to Iraq's government and its allies for allowing him to escape IS

"It's miserable here but compared to what we left behind, we feel like we're sitting on the White House lawn," declares Ali Hamdani Shimmari as he shelters against a brick wall in a futile search for shade.

Never mind that there is not a speck of green, much less a flower, on this hardscrabble terrain a long way from the American seat of power.

"We're so grateful to Iraq and its allies who bombed Sharqat, and to Iraqi forces who took us out," Mr Shimmari says.

But the new enemy is scorching 50-degree heat, and hunger. And it is not clear when they will escape from this one.

"They are living inside houses that are unfinished, in schools that are inhabited," says Sara Alzawqari of the International Committee of the Red Cross. "They have no food, no electricity, no water."

The ICRC is seeking to improve living conditions for the millions of displaced people in Iraq

Long queues form, mainly men in long white robes and red chequered headdresses, to receive a first-starter kit from the ICRC, which includes everything from a small cooker to a plastic cooler, sacks of rice and hygiene kits.

Nineteen-year-old Jassim stands with a vacant stare next to his mound of goods.

Responsibility for a family of 11 lies on his thin shoulders. IS kidnapped his father a year and a half ago and there's been no news since then.

"Our life in Sharqat was horrible. Daesh destroyed it," he says. "We have nothing now, but we have security."

"It's a risk to stay and a bigger risk to leave. And once you leave, where are you going to go?" asks Ms Alzawqari.

'Daesh will collapse'

The recent major battle for Falluja, just to the west of Baghdad, ended more quickly than everyone expected.

Residential areas of Falluja sustained heavy damage during the recent battle for the city

Some 85,000 civilians fled and many do not want to return to a city in ruin that has been cursed by violence since 2003.

No-one is certain how long the battle for the biggest prize of Mosul will take.

"We think Daesh will collapse," Gen Ghanimi says. "We know they are bankrupt and unable to hold their ground."

A soldier from Mosul, Abdul Majid Nazal, adds further detail as we stand on a newly-erected temporary bridge spanning the River Tigris which will help hasten the army's move north.

"Most Iraqis who joined [IS] won't fight because they know they will get killed. So most of are escaping to Turkey, and Syria."

Iraq's military has built a temporary bridge over the River Tigris to help the advance on Mosul

Mosul will be a major testing ground for an ill-equipped army backed by Kurdish Peshmerga units and local fighters.

Added to the mix will be small clusters of Western special forces personnel, hundreds of American military advisers working closely with the army to strengthen logistics and planning, as well as Iranian Revolutionary Guards.

Iraq's army chief insists only Iraqis will do the fighting.

But to take back and hold Mosul, and take care of its people, Iraq needs much more help from the world.