Viewpoint: Is bloodied Syrian boy Omran Daqneesh just another image?

- Published

The iconic image of a bloodied Syrian boy in an ambulance has sparked international compassion but, asks Lina Sergie Attar, can it now transcend being just a hashtag or viral moment and become a movement to end the war?

"He looks like a statue." That's what my 11-year-old daughter said when she saw the video of five-year-old Omran Daqneesh covered in grey dust and fresh blood, sitting on a bright orange chair in an ambulance.

He sits in complete silence, staring ahead with deadened eyes.

The statue moves. He touches his bloody forehead and studies his hand with confusion.

Then little Omran does what every parent has witnessed their child do. After a moment's hesitation, he wipes his hand on the chair. Except our children have done the same with ketchup, ice cream, chocolate. Not blood.

Yearly tradition

Once again, the world has been shocked by the image of a Syrian child.

Russia has denied that its warplanes bombed Omran Daqneesh's home in rebel-held Aleppo

Hundreds of civilians, many of them children, have been killed in Aleppo in recent weeks

Omran was rescued with his family by the Syrian Civil Defence (also known as the White Helmets) after a reported Russian air strike hit his home in rebel-held eastern Aleppo on Wednesday.

His photo has been featured on the front page of every major international newspaper, discussed on the news, and has gone viral on social media.

It seems the end of summer has become a yearly tradition for the world to awaken to Syria's tragedy through the photos of its suffering children.

Three years ago, it was the images of gassed children from the Ghouta region outside Damascus, who suffocated to death after a chemical weapons attack on their neighbourhoods - widely blamed on regime forces - as they slept in underground bomb shelters.

They looked like perfect porcelain dolls lined up in a row, waxy and unblemished.

One year ago, it was the photo of Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi who washed up on a Turkish beach after drowning while trying to reach Greece with his family as they fled the war like millions of other refugees.

Alan Kurdi (L) and his brother Galib both drowned trying to reach Greece. An image of Alan's body on the beach sparked an international outpouring of compassion

Alan captured the world's hearts and compassion with his red T-shirt, navy shorts, and sturdy little shoes - a universal toddler outfit - and became the symbol of the plight of refugees.

Omran is the Syrian icon of 2016.

Unfortunately, every year these images are followed by millions of tweets, likes, and shares; they inspire public outrage and an outpouring of compassionate donations to aid organisations; and then, after a few days or weeks, the image and the crisis are forgotten.

The world moves on. Air raids by the Syrian government and its allies continue to drop bombs of all sorts on civilians; so-called Islamic State (IS) continues to terrorise Syrians living under its control; the death toll rises and the refugee crisis continues to escalate.

The international community and the UN wring their hands. And then about a year passes and another image goes viral. Over and over.

Deafening silence

Chemical weapons attacks, mass displacement, barrel bombs, air strikes, forced starvation, torture: every vile act of war imaginable has directly affected Syrian children since 2011.

The UN says children and their families in Aleppo are facing a catastrophic situation

For children like Omran, all he has known in his life is war.

For millions of Syrian children growing up during this gruelling conflict, their realities are bleak and their futures even bleaker.

If they stay in their homes, they are sitting targets of bombs and missiles. They may suffer hunger and illness if they live in besieged areas. They may not have access to schools or even access to safe passage to school.

If they leave with their families across Syria's borders to a neighbouring country, they may face being forced to work as child labourers to support their families.

Moving beyond the neighbouring countries' boundaries poses even greater risks: of drowning on the way to Europe; being trapped in detention camps; and finally, after reaching safe havens, they still are subjected to discrimination and hate campaigns.

Syrian children are unwelcome wherever they go.

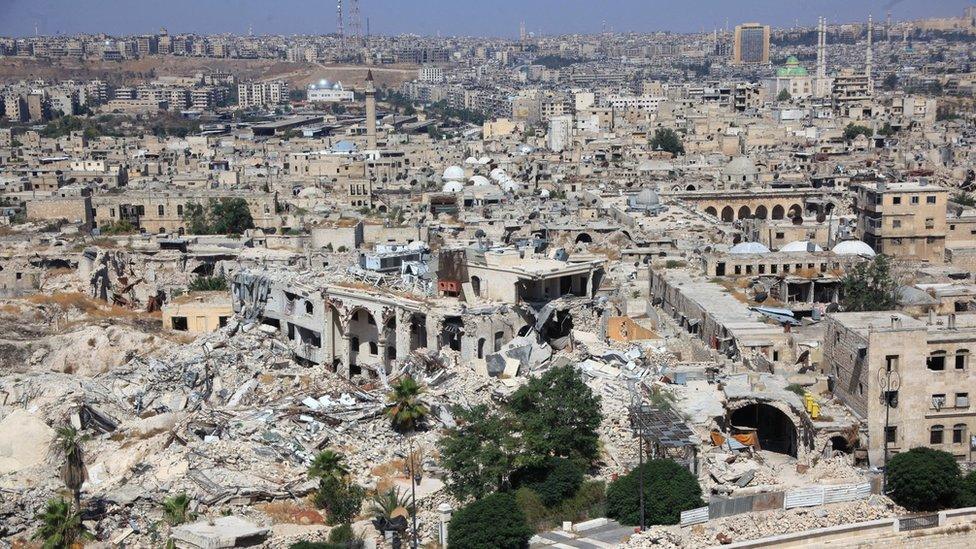

Large parts of Aleppo have been destroyed since the civil war reached the city in 2012

This week, one image, one boy, one moment, was elevated above the dozens of moments that have happened every single day in Syria for the past five-and-a-half years.

Every day there are so many Omrans whose images you will never see and whose names you will never know.

And unlike lucky Omran, those kids don't survive.

This is not a hashtag moment. This is not a viral moment. This is a moment that must become a movement to end the war.

He looks like a statue. He stares at the camera, at us, in complete silence. Literally shell-shocked. As if he already knows that silence is the only appropriate response to what has just happened.

A child's crushing silence to match the world's deafening silence that Syrians know all too well.

Lina Sergie Attar is a Syrian American writer and architect. She is the co-founder and CEO of the Karam Foundation, external, which provides humanitarian aid to Syrians. @amalhanano