Can IS survive killings of its core leadership?

- Published

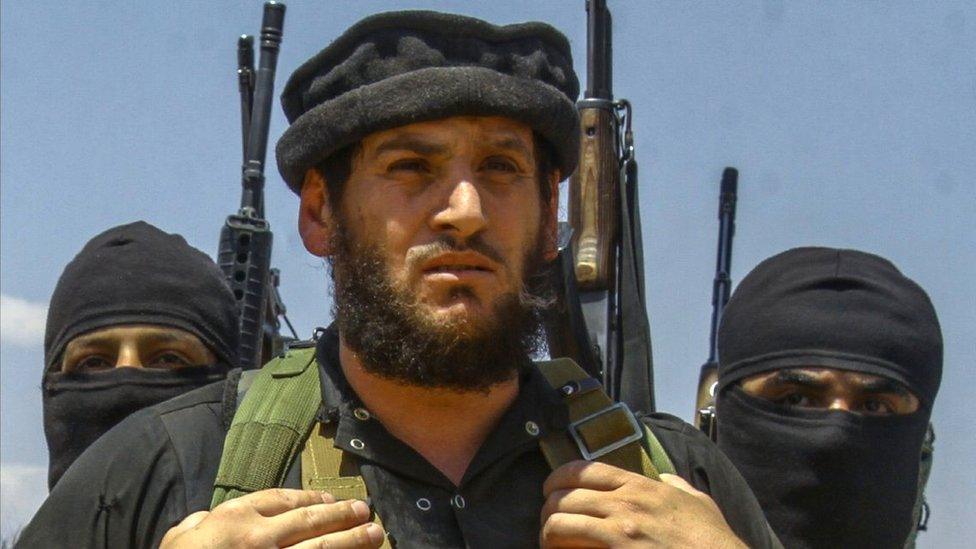

Both the US and Russia say they carried out the air strike that killed Abu Muhammad al-Adnani

On Tuesday, the Islamic State group announced the killing of Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, its spokesman since 2010.

Amaq, one of the group's media outlets, said he was targeted as he was inspecting the preparedness of fighters in Aleppo.

The US said Adnani was targeted by a precision strike in al-Bab, the second most important stronghold for IS in Syria after Raqqa. Russia also claimed responsibility for the killing of one of the most significant jihadist operatives over the past half-decade.

Taha Subhi Fallaha, Adnani's real name, was born in the town of Binnish, in the countryside of the north-western Syrian province of Idlib.

Adnani helped oversee the seizure by IS of much of northern and western Iraq in 2014

He was one of a handful of IS leaders left of the generation who founded the group after the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, rebuilt it after American troops withdrew in 2010, and oversaw it taking control of an area similar in size to the United Kingdom in 2014.

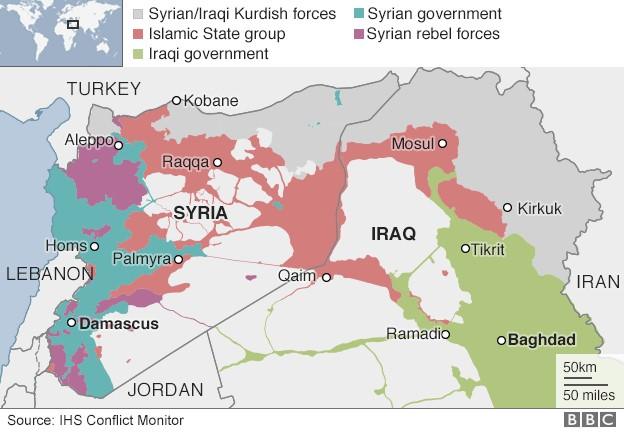

Before Adnani's death, IS had lost at least 50% of its territory in Iraq and 20% in Syria, but still controlled something the size of Greece.

Multiple roles

The impact of the steady losses is a test to the group's ability to endure, as much of its appeal hinged on its claim to have established a caliphate in Iraq and Syria in June 2014.

And yet, a less discussed question is whether IS will survive the steady decapitation of the leaders who made the group what it is today.

According to Khaled al-Qaysi, an Iraqi expert on IS, only two of them are still alive.

One of the reasons why those leaders held many different roles before their deaths was that the group relied on those it trusted the most to handle its operations.

Adnani, for example, was the group's spokesman but also its general emir in Syria and the man in charge of foreign operations orchestrated from Syria, primarily in Western countries.

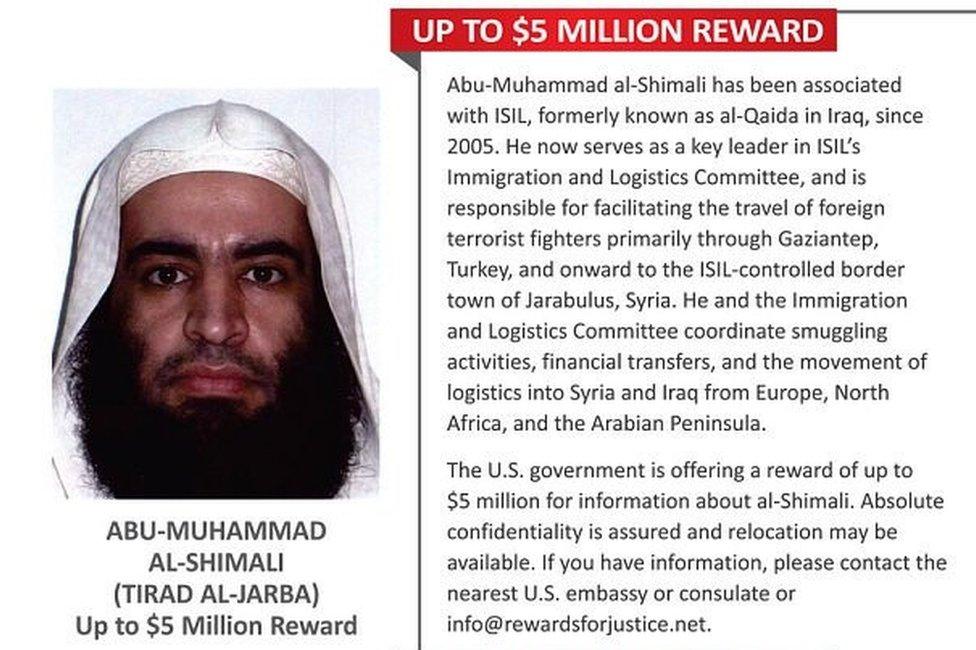

Adnani's likely replacement as head of foreign operations is Tirad al-Jarba, a Saudi national known by his nom de guerre Abu Muhammad al-Shimali, who is one of the group's founders and has handled its foreign fighters.

The US government has offered a $5m reward for information about Abu Muhammad al-Shimali

Another example of IS relying on long-standing leaders to handle several roles was Abu Ali al-Anbari, who blew himself up after US forces ambushed him near the Syria-Iraq border in March.

Before his death, according to a detailed obituary published by the group's Arabic-language al-Naba newsletter, Anbari had been asked to leave his role as a preacher in his hometown, Tal Afar near Mosul, and take on responsibility for management of IS finances.

Transitional phase

The loss of the old guard is clearly aggravating the group's problems and might represent the greatest challenge it has faced since the US-enabled uprising against it by Sunni Arabs in Iraq in 2005-6.

Whether the group will survive this transition depends on how far the old guard shaped and defined it.

The transition to the second and third tiers of leadership is already well under way, and the process could affect the overall direction IS takes and the way it operates.

The emerging leaders grew up within the group as it moved from a foreign franchise established by jihadist veterans to a predominantly Iraqi insurgent group, and then back to a hybrid local group with a global agenda.

Many of them also grew up under the US occupation in Iraq and in an environment shaped by sectarian tensions and civil wars.

Before Adnani's death, IS had lost at least 50% of its territory in Iraq and 20% in Syria

The decapitation of the old guard could thus inject new life into IS, with emerging commanders more dogmatic, resilient and attuned to local dynamics than previous ones.

Almost exactly two years after the launch of the US-led operation to degrade and ultimately destroy IS, the group still controls 50% of the territory it once held in Iraq and Syria, including critical strongholds such as Mosul and Raqqa.

The remaining half could crumble faster than the first half, but it could also endure longer.

The ability of IS's emerging leaders to maintain the organisation will depend on how they manage the fight for the remaining half.

Regardless of what happens next, this is a long war, and no-one should hold their breath.

Hassan Hassan is a resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, Washington, and co-author of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror