Syrian refugees living in fear as Lebanon tightens its laws

- Published

Syrian refugees in Lebanon have been effectively stripped of many of their rights

Faced with one of the most severe refugee crises in the world, Lebanon has been toughening up its policies towards Syrians who have fled there, leaving many in an increasingly vulnerable state.

In one of the latest examples, authorities in the southern village of Kfarruman gave those who did not have a local sponsor 15 days to leave.

I put it to Khalil Gebara, the interior minister's adviser for municipal affairs, that the move was illegal.

"If we're going to be literal about it, yes," he told me.

"But reality is one thing and the law is another," he added. "Our role is to balance the reality of people's fears against the law. We're always looking for the middle ground."

Kfarruman may have taken things further than other municipalities, but the trend is nationwide.

Municipal police have been cracking down on Syrian refugees and local authorities have been imposing curfews, often on security grounds.

Ghida Frangieh, a lawyer with the non-governmental organisation Legal Agenda, said municipalities had no authority to impose curfews, either on Lebanese citizens or foreigners.

Yet municipalities across the country have persisted in the practice, with no consequences.

Annual fee

On the surface, the open and increasingly normalized violation of the law by local authorities is the main cause of the refugees' increasing vulnerability.

But Syrians in Lebanon have been effectively stripped of many of their rights through the application of one devastating but legal policy, initiated by the central government.

In October 2014, the cabinet introduced new rules for Syrians living in Lebanon, requiring them to renew their residency permits.

Some Lebanese took to the streets to protest against the curfews imposed on Syrian refugees.

All Syrians aged over 15 had to pay $200 (£151) each year to renew their permits, and provide a range of documents as well.

'It became logistically much more difficult for them to gain residency," said Mathew Saltmarsh, a spokesman for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

"Part of the change was also a pledge not to work. If they're committing not to work their opportunities for livelihood are restricted."

A year-and-a-half after the new regulations came into force, one-in-two registered refugees lives outside the law, according to the UNHCR.

Police raids

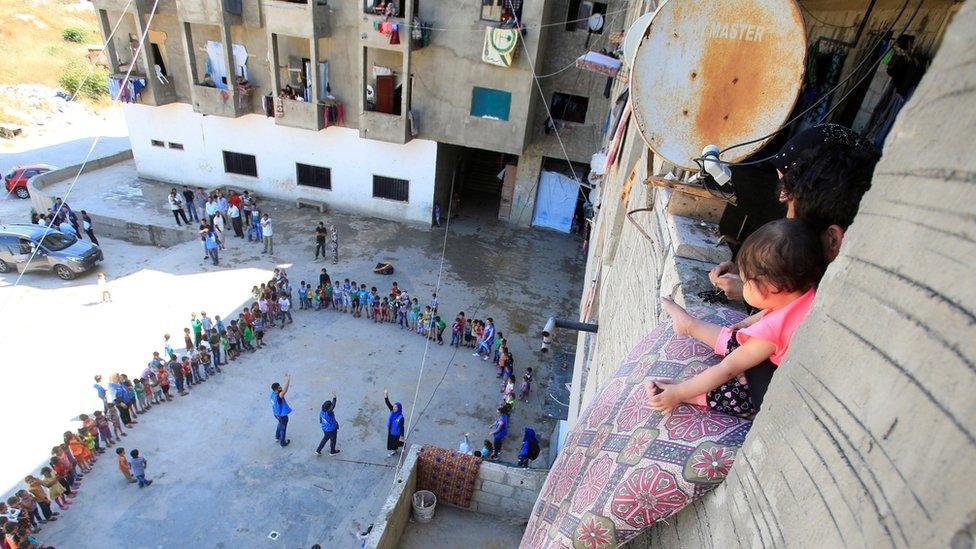

Umm Khalaf's family are among dozens living illegally at a four-storey compound on a hilltop in northern Lebanon that overlooks the Mediterranean Sea.

She said they simply could not afford to get temporary residential permits.

"We've all become illegal," she told me. "We're always anticipating a raid on the compound, and we live in fear."

Security forces frequently carry out raids that result in mass arrests.

The majority of Syrian refugees live below the poverty line in Lebanon

"They raided the compound, searched houses and rounded up 40 of us," one young man at the compound told me.

"They held us for seven days and then released us, but my papers are still with them, and I can't go anywhere. If one of my children gets sick I can't take them to the doctor."

The men are usually released soon after being detained, but the insecurity of living illegally affects every aspect of their lives.

Children, who are less likely to be arrested, are being forced to provide for their families, and school enrolment is going down.

Earlier this year, Human Rights Watch said Syrians who had lost their legal status were "restricting their movement due to fear of arrest", and that "almost all said they could not pay the $200 annual fee' for residency permits - a huge sum given that the majority live below the poverty line.

HRW warned that the loss of their legal status made refugees "vulnerable to labour and sexual exploitation by employers, without the ability to turn to authorities for protection".

'Stuck with them'

It has also empowered municipalities to take ever harsher measures against refugees.

More ominously for the refugees, these measures appear to enjoy significant backing among the Lebanese population.

"They've [the refugees] taken our pupils' places at school," said Mariam Hamze, who teaches at a local school in Kfarruman.

"When the municipality takes a measure it says is for security purposes, we stand by the municipality," said another local who had recently returned to the village.

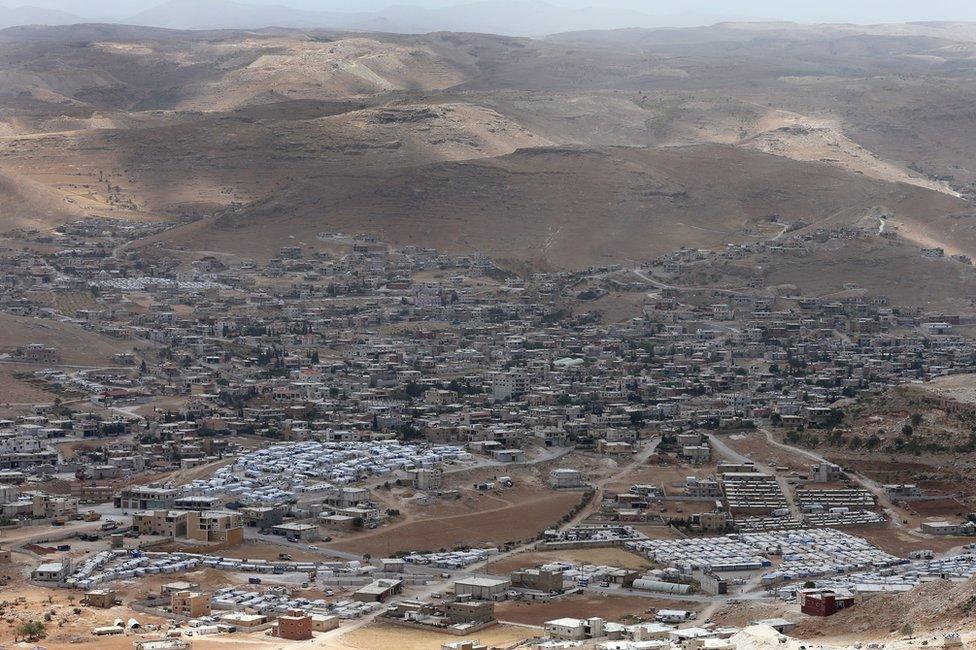

One in every five people living in Lebanon is a Syrian refugee

The pressure on infrastructure is severe, with the number of Syrians living in some villages approaching the number of Lebanese and in some cases even surpassing it.

There are more than a million Syrians officially registered as refugees in Lebanon, a country that has five million citizens, but the real number is believed to be higher.

By comparison, the UK - which is 24 times larger than Lebanon and more developed - has only agreed to take in 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2020.

People in Lebanon watched earlier this year as tens of thousands of refugees and migrants were left stranded at camps by the closure of Greece-Macedonia border and the EU negotiated a deal with Turkey that saw "irregular migrants" sent back across the Aegean Sea.

This has fuelled resentment here.

"Which country in the world receives people the way Lebanon has received Syrians?" asked one man in the northern coastal village of Amcheet following reports of trouble between the local authorities and a group of Syrian men.

"We are the only ones feeling their pain. Europe is turning away, America is turning away, Britain is turning away, and we're stuck with them."

Outside the law

Lebanon's interior ministry says it is trying to rein in some of the excesses of the municipalities, but insists it must balance that against the reality of massively overburdened infrastructure, as well as security concerns.

"Hundreds of Syrians do not have any papers, which means we do not even know who they are," said Khalil Gebara, the ministry adviser.

"We must remember there are bombings that have taken place in Lebanon and there is a war that's 50km away from the Lebanese border."

Children are being forced to provide for their families and school enrolment is down

The reality for the refugees, however, is that the residency policy, coupled with the measures imposed by municipalities and a tendency to blame them collectively for security problems, has left them defenceless.

The social affairs ministry has promised a new policy that it says will help the refugees who are no longer legally resident, but it has yet to come into effect.

Meanwhile, the refugees have almost no recourse to justice.

Ghida Frangieh of Legal Agenda said Syrians could, in theory, appeal against municipal decisions in court, but that most were either not aware of their legal rights or had no valid residency permit, which discouraged them from any contact with the authorities.

They also feared repercussions if they appealed, she added.

"The Lebanese state has constructed a legal situation for Syrian refugees that is fragile, unstable, and leaves them outside the law and the protection it affords."

"Their mere presence as Syrians without permits on Lebanese soil has made them criminals. This strips them of their human dignity and creates a rationale for all sorts of behaviour."