The war in Syria: Behind the scenes at the US-Russia talks in Geneva

- Published

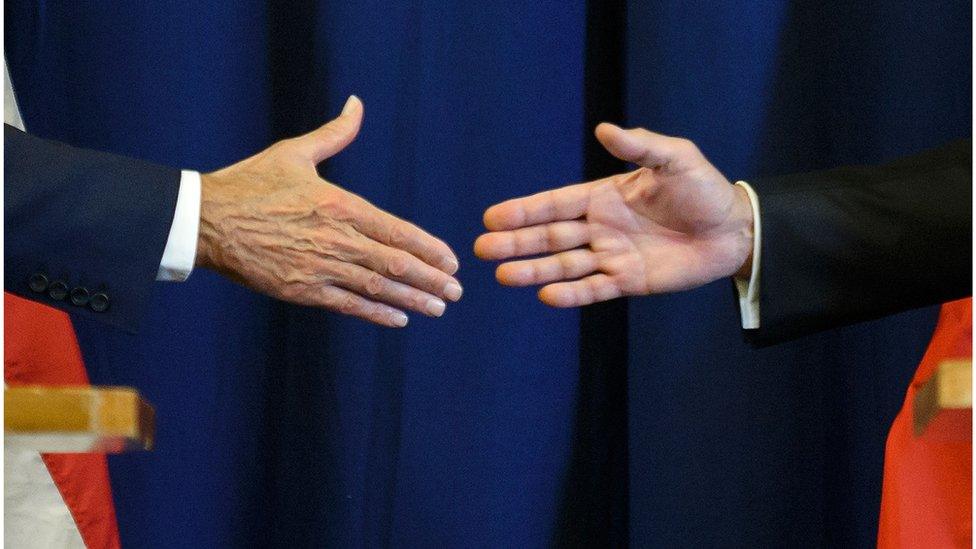

The result of many long months and late-night talks

How do you cut a deal on military co-operation with a country you see as an existential threat?

That is how US generals characterise Russia: it is the starkest version of those "gaps of trust" President Barack Obama blamed for holding up a ceasefire deal on Syria.

And that mistrust helps explain the puzzling, even bizarre twists and turns of the week that finally ended in an agreement between the rival powers.

We now know, of course, what the deal is: the promise of joint US-Russian military action against Syria's al-Qaeda affiliate, the Nusra Front (recently renamed Jabhet Fateh al-Shams) and so-called Islamic State, which is important to Moscow.

But Russia must first put all its weight behind a ceasefire in the civil war, especially an end to bombing raids against civilians by its ally, the Syrian regime. And both must stop air strikes against US backed rebels they say are working with Nusra fighters. US allied opposition groups must observe the truce and any who are fighting with Nusra Front must break ranks with it.

Mistrust marred the negotiations, which took place over months

It is the Secretary of State John Kerry who has doggedly promoted this unlikely military partnership as the only way to stem the violence of Syria's conflict.

Negotiations with his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, had been what administration officials called "complicated and difficult" since July, taking one step forward, then two steps back.

Syria: The story of the conflict

Now he was poised for another session to discuss a '"final" proposal offered last weekend by an impatient US administration, according to senior officials quoted by the Washington Post. But even the timing of this was contested.

For the Russians it was all "Go": they announced there would be a meeting in Geneva, even as the US insisted it was still "No Go".

The State Department called off one flight at the last minute and cited internal discussions among government agencies, while postponing another.

"We just don't think it's worth his while to go at this point", said spokesman Mark Toner, precisely half an hour before journalists were suddenly told to head to the airport.

Although John Kerry is mindful of the time, it is his counterpart Sergei Lavrov who was kept waiting

The chaotic messaging was at least partially explained by a late response from Russia to the US proposal, which threw uncertainty into Mr Kerry's timetable.

But in the meantime Mr Lavrov had emerged in Geneva, presenting the intriguing possibility that he might "empty chair" the secretary of state, a man who believes passionately in the power of being in that chair for face-to-face meetings as often as he can.

Even as we boarded for Geneva, senior administration officials were trying to dampen our expectations.

"There seems to be some anticipation that we're reaching a culminating period," said one, warning there was no guarantee they were "on the cusp of finishing".

That was clearly the aim though, and once we landed in Geneva Mr Kerry went straight into meetings described by one observer as "businesslike" and "crisp".

Every hour or two the sessions broke and delegations filed out en masse to take stock, winding through the foyer filled with journalists, drinking coffee.

Mr Lavrov entered the press room with pizzas "from the US"

The secretary of state seemed upbeat: "Let's go draft a statement," he was overheard saying to his delegation after one of the meetings.

Then the momentum ground to a halt.

Mr Kerry was back on the phone with the presidency and the Pentagon in DC to get approval for the latest draft.

The Pentagon in particular has remained deeply sceptical, suspicious that Moscow would not live up to its word, after the crumbling of a previous truce. It was reluctant to share targeting information with an air force that has bombed America's rebel allies.

The Russians meanwhile, were left with too much time on their hands.

After five hours, the US delegation sent them pizza as a "gesture" to apologise for the "pause".

The waiting press also received two bottles of vodka, "from Russia"

Mr Lavrov immediately re-gifted the pizzas to the restless press, adding some bottles of vodka "from Russia".

He mused that the "power vertical" in a democracy works slowly, and said he hoped for an answer "before Washington goes to sleep".

That gave us something to ponder for another three hours. Was it a Russian publicity stunt to upstage the Americans? An attempt at Russian soft-power? The Russian media presented it as a joint snack of "American comfort food and Russian bonhomie".

By now the day had run past midnight and US embassy staff inadvertently caused another delay while changing the dates on the podium signs, just as Messieurs Kerry and Lavrov arrived to shuffle impatiently in the doorway.

The delegations, accompanied by the UN envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura (centre), wait in the doorway of the press room for the date to be changed on the podium

Both men were cautious, although Mr Lavrov pointedly noted the secretary of state had helped dispel Russian suspicions that the Americans were not serious about going after the Nusra Front.

Mr Kerry's speech was peppered with caveats, mindful that without any US military assets in the civil war, much rested on Russian good faith. Seven times he emphasised the deal would work only if implemented.

"President Obama has gone the extra mile here in order to try to find a way, if possible, to end the carnage on the ground in Syria," he said, a view doubtless held strongly in Washington.

A deal cut with the country seen as an existential threat