Syria war: Aleppo's children and families suffer conflict's horror

- Published

Hani, aged eight, called for his father as he left hospital

Two children this week made me think very hard about the waste and horror of this war in Syria, of every war.

The first was a boy of eight called Hani Jadid. He was lying on a trolley outside Aleppo university hospital.

The day was hot and all he was dressed in was a disposable nappy. A tube came out of it leading to a plastic bag to collect his urine.

His right arm was gone, amputated above the elbow. The stump had been heavily wrapped in new, cream-coloured bandages, like both his legs.

Hani was being sent home to start his new life. He will have to live it without four cousins, who were killed by the shell that maimed him.

Hani was wounded before the ceasefire

He groaned with pain and called for his father, who was not there, when he was lifted by a male orderly and carried a few paces to a taxi.

An uncle and a cousin who had been sent to pick him up got in and the taxi drove away. Hani had been placed on the back seat and his head was squeezed against the door.

He was wounded before the ceasefire, in a village under government control about an hour's drive from the centre of Aleppo.

But geography, politics and timing cannot have been much on the mind of an eight-year-old whose friends are dead, whose arm is gone, facing an hour's agonising drive.

Inside the hospital, watched over by her mother, was Rawda al-Youssef, a seven-year-old girl who looked small for her age. She had been shot in the back, and was sleeping. Her mother, Turkieh, had no idea where the bullet had come from and did not seem to care.

But it was lodged in her spine and Rawda was paralysed.

Rawda al-Youssef, aged seven, was paralysed by a silent bullet while eating dinner

Her mother's worries were much more specific, about Rawda's future and how she would look after her. She has five other daughters and two sons, one of whom is handicapped. Her husband is a shepherd.

Hani and Rawda are two children whose lives have been changed forever. Their injuries will affect everyone in their close families for years to come. But neither died.

In the carnage of war in Syria, they were not even a blip in the statistics.

Without warning

The sheer numbers of dead and wounded in Syria are overwhelming. The UN's Syria envoy Staffan de Mistura estimated in April that 400,000 had been killed. Many more have died since then.

People can be forgiven if they find it hard to grasp the horror of the deaths of 400,000 individual human beings.

Unless they were suicide bombers, the chances are that those people - they had not yet become "the dead" - did not think when they had seen their last sunrise when they woke up on the final day of life.

People rarely do. It is always going to happen to someone else.

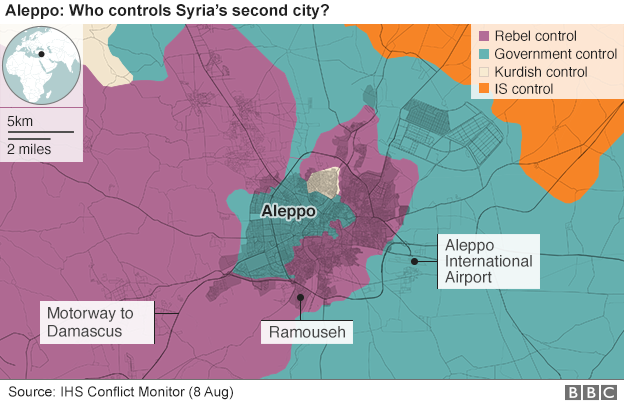

Inside the fragmented city of Aleppo

Turkieh, the mother of Rawda, talked about how a gunshot and a paralysing wound were the last thing on her mind when they sat down to eat dinner outside their house. The worst of the summer heat has gone, and the evenings are breezy and cool.

Rawda, she said, was an energetic and loving seven-year-old. She was chatting to her father when she was shot, sitting next to him. Nothing was wrong, until it happened.

"We finished dinner and she sat next to her father. I thought maybe she'd been hit in the back by a pebble. She asked her Dad to carry her indoors.

"We took her into the house, took out a torch [only people with generators have power], and we saw the blood coming out of her back. A bullet had hit her in the back without any sound."

'My heart is dead'

A middle-aged man lay in a room further down the corridor with what remained of his family. He was a dentist called Mohammad Marzen Saboni and talked about how his wife and two-year-old son were killed.

"Last Friday, we were outside the house, the whole family. Nothing was going on, there was nothing happening in the street. Then a terrorist mortar fell.

"My wife was badly hurt and died. And then my son passed away. We were just walking in the street. I never thought it would happen."

Mohammad Marzen Saboni lost his wife and son in the attack which crushed his legs

Mohammad, like many people in West Aleppo, means armed rebels when he uses the word terrorist. He looked down at his smashed legs as he talked about the attack.

Orthopaedic surgeons had fixed stainless steel rods up and down his legs to help the fragments of bone knit together. He said his nerves were so badly damaged that the surgeons were not certain how much he would recover.

"I blame the terrorists, we are innocent, kids, civilians. I just want to walk again. My heart is dead."

His nine-year-old daughter Mayar was in the next bed with both legs in plaster. Someone had given her a doll. It was propped up next to her pillow, a Barbie in a pink box she had not tried to open.

Mayar looked away from anyone who tried to catch her eye. A nurse tried to show her the doll but she scowled. Mayar had seen her mother and her baby brother die and, like Hani Jadid, the boy outside the hospital, she was facing a new, much darker world.

Mohammad Amer, 14, and Mayar, nine, lost their mother and baby brother in a mortar attack

Her 14-year-old brother Mohammad Amer watched the attack happen but was not injured. He sounded as weary as an old man.

"There's no life here. We're very tired. All I want from the future is to see my father and sister walking again."

One estimate is that 11.5% of Syria's population have been killed or injured since the first shots were fired in Deraa in the south of the country in March 2011. The report, by the Syrian Centre for Policy Research, said that 1.9 million had been wounded.

Life expectancy had gone from 70 in 2010 to 55.4 in 2015.

What do more than 400,000 dead bodies look like?

Old Trafford football ground, Manchester United's theatre of dreams, holds 76,100.

Syria's theatre of nightmares could fill it six times over.

- Published8 August 2016

- Published11 August 2016

- Published13 September 2016

- Published15 September 2016

- Published14 September 2016