Islamic State conflict: How will the battle for Mosul unfold?

- Published

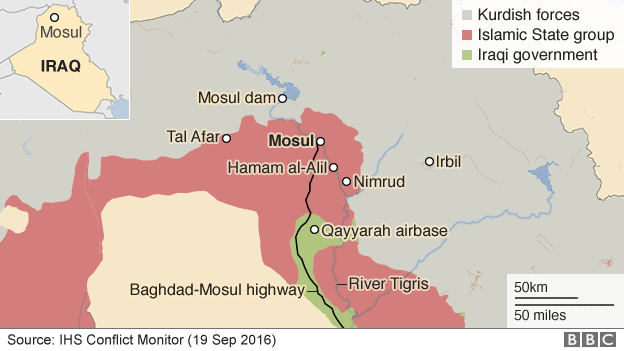

A spectrum of forces are closing in on Mosul from all directions

Little by little, plans are leaking out regarding the imminent battle to remove so-called Islamic State (IS) from Mosul, Iraq's second largest city.

Michael Fallon, the UK defence secretary, said military co-operation agreements were finalised on 23 September, external, adding that "the encirclement operation will begin in the next few weeks" with Mosul being liberated "in the next few months".

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan went even further, obligingly providing the start-date, external of the offensive, 19 October.

What can be said with certainty is that the liberation of Mosul will be a multi-phased operation.

First the logistical base for the operation must be established at Qayyarah airbase, a facility 40 miles (60km) south of Mosul that was seized by the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) in early July.

Since then, the airbase has been refurbished to enable the landing of cargo aircraft, enabling ammunition, fuel and rations to be flown directly to the front line rather than being trucked up from Iraq's military depots near Baghdad, 185 miles further south.

Around 560 US military advisers have been moved to Qayyarah to advise and assist the offensive. US and French long-range artillery systems have been emplaced, with mobile howitzers able to range out half the distance to Mosul and with rocket launchers able to shoot into the city itself, taking under 20 seconds and with great precision.

Sealing off the city

Qayyarah is also the collecting point for the Iraqi forces that will liberate Mosul. These are mainly Iraqi army forces drawn from across the country into multi-ethnic, cross-sectarian national units.

There are around 11 Iraqi army and special forces' brigades ready to attack, with each brigade numbering about 2,000 troops.

Shia-dominated Popular Mobilisation units will be involved in the battle for the mainly Sunni Arab city

A further five units of tribal or paramilitary police forces are also ready, comprising about 6,000 troops, mainly Sunni Arabs from the broad Mosul area.

The Kurdish Peshmerga forces and a handful of small Kurdish-backed paramilitary police units manned by micro-minorities (Christians and Kakai) are circling Mosul to the north-east and will close the blockade on the city from that side.

A formula also seems to have been worked out to allow security volunteers from Shia-populated southern Iraq to indirectly support the battle without alarming the predominately Sunni residents of Mosul.

These Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation forces) will be used to secure the empty rural areas and roads south of Qayyarah and west of Mosul but will not be played into the urban battle.

Desert push

The next phase of the battle will be a multi-pronged advance on the outskirts of Mosul.

Most likely the main thrust will drive up the Baghdad-Mosul highway on the west bank of the Tigris River, halting when the southern outskirts of Mosul are reached.

The international anti-IS coalition will provide air support for the battle

Another column may swing out west of Mosul into the desert along pipeline roads and tracks to close off the city from that direction, preventing IS from bringing in reinforcements or slipping away to Syria.

A final set of forces may push up to Mosul on the east bank of the Tigris, aiming at the eastern side of the city.

This phase will unfold in fits and spurts: one day 10 miles will be gained easily, another day there will be tough fighting at an IS strongpoint or a pause to bring up supplies.

There will be images of Iraqi Security Forces and Popular Mobilisation units streaming through the desert in large vehicle columns, interspersed with days of air strikes to eradicate stubborn IS fighters.

By the time of the US elections on 8 November the edges of Mosul will likely have been contacted at multiple points.

Civilian fears

During November and December the main battle will likely begin.

First a new base of operations will be established in an area next to the city that can be fortified, such as Mosul's airport to the south.

This will give the ISF and coalition a place to position headquarters, supplies and artillery.

The battle for Mosul could lead to a mass exodus and major humanitarian crisis

For the Iraqi and coalition forces the issue of civilians will be a tricky factor. Perhaps 700,000 people may still be in Mosul, the largest population to be present during an urban liberation battle in Iraq's war against IS.

As liberating forces line the perimeter of the city, the displaced people will start to leak out in huge numbers once IS can no longer prevent the exodus.

This is one reason why coalition forces may hesitate to approach Mosul before they are ready to take the whole city: the preference is for Mosul civilians to stay in place and hunker down during fighting.

Keeping civilians off the streets will also allow cleaner air strikes that focus on IS vehicles and fighters.

Swift collapse?

For many months the coalition has been intensively watching the IS defenders, profiling their movements and their defences.

Air strikes will be accelerated in places where the coalition wishes to breach the defences. IS commanders will be intensively targeted to disrupt the movement's ability to mount a cohesive defence.

Ultimately, however, IS may not fight very hard for most of Mosul city. The urban area is far bigger than anything they have attempted to defend before: about 10 miles wide by 10 miles long with a 30-mile perimeter - twice as large as their defence of Ramadi.

IS stormed into Mosul in June 2014

Instead the 2-3,000 IS fighters are likely to pick a couple of neighbourhoods to strongly defend.

The government centre in western Mosul is a symbolic location and liberation cannot be announced until it is retaken.

The old city is full of narrow streets in which the security forces cannot use armoured vehicles, artillery or air strikes with ease.

When these defensive pockets collapse - and they might collapse surprisingly quickly, as they did when Falluja was liberated within three weeks in June - the final stabilisation phase of the operation begins.

Fleeing IS fighters will need to be distinguished from displaced persons, law and order will need to be quickly but humanely established. These tasks may prove to be more difficult than the battle itself.

Dr Michael Knights is the Lafer Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has worked in all of Iraq's provinces, and spent time embedded with the Iraqi security forces. His recent report, external on the Iraqi security forces is available via the Washington Institute website. Follow him on Twitter, external