Syria war: How Moscow’s bombing campaign has paid off for Putin

- Published

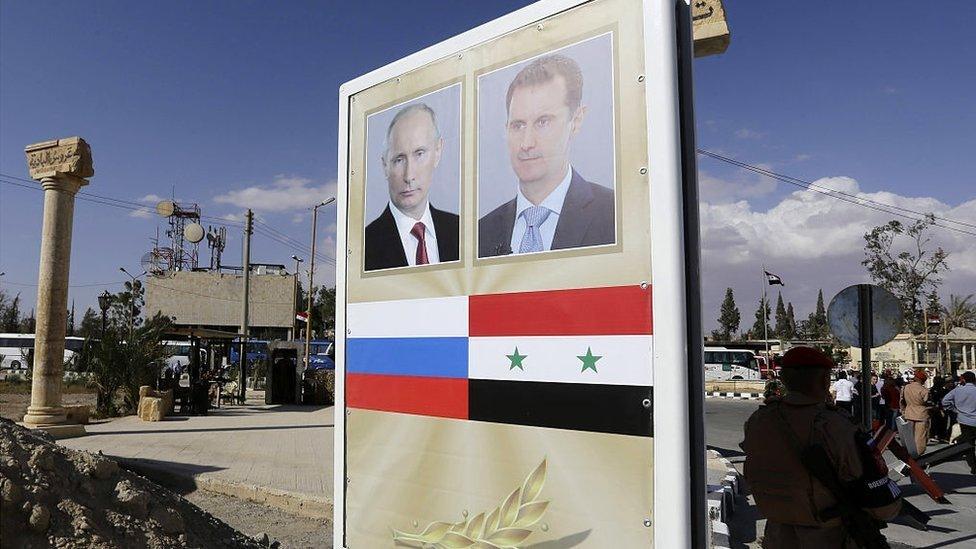

Russian forces have been operating in support of the government of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria for a year.

Their impact has been significant.

When they arrived, there were fears that government forces were close to collapse.

This position has largely been reversed.

It is the Syrian government - while still fragile - that is now on the offensive with a brutal bid to recapture the whole of the city of Aleppo.

Initially seen by US analysts through the prism of recent Western military involvements in the region, many pundits were quick to dismiss the Russian effort as likely to fail.

The Russian military, it was said, was not up to expeditionary warfare. Russia would quickly find itself bogged down in a Syrian quagmire.

Military 'success'

Things have turned out very differently.

Roger McDermott, senior fellow in Eurasian studies at the Jamestown Foundation - and a long-time watcher of the Russian military - says: "[Western] observers have been generally impressed by Russia's deployment in Syria, mainly reflecting a sense of disbelief that they proved to be capable of planning, executing and sustaining such a complex operation and dealing with the logistical issues involved in supplying forces at great distance from Russia."

But what exactly were Russia's goals in intervening in the first place?

Russia, of course, has had a strategic relationship with Syria going back to Soviet days.

It has long maintained a small naval base on the Syrian coast and has close ties with the Syrian military, being its principal arms supplier.

Syria had become Moscow's last toe-hold of influence in the region .

It was the fear of this relationship unravelling that prompted President Vladimir Putin to act.

While it is Russian air power that has been the main focus of news reporting on the Russian intervention, it is as much the intensified training and re-equipping of the Syrian army that has also been a crucial factor in helping to turn around President Assad's fortunes.

Russia's air campaign: Key moments

30 September 2015 - Russia carries out its first air strikes. Syria says it requested intervention to help in "the fight against terrorism".

10 November 2015 - The Syrian army, aided by Russian strikes, lifts two-year-long siege by IS on the key Kuwairis airbase in eastern Aleppo province, marking its first victory against IS since the Russian intervention.

24 November - Turkey shoots down a Russian Su-24 fighter jet near the Turkish-Syrian border

December 2015 - January 2016 - Benefiting from Russian support, the Syrian army makes territorial gains in various parts of Syria and declares Latakia province rebel-free

24 March 2016 - Syrian army backed by Russian strikes inflicts a major symbolic and strategic defeat on IS, recapturing the historic city of Palmyra

September 2016 - Russia acknowledges providing air cover to the Syrian troops in their bid to seize control of Aleppo city.

That is not to say, though, that Russian and Syrian military goals are identical.

While the Syrian government insists it still wants to recapture all the territory it has lost, Moscow's approach, according to Michael Kofman of the Wilson Center's Kennan Institute, is very different.

Russia's commitment to its relationship with Syria has been central to its intervention

"Unlike Syria and Iran, Russia has no interest in fighting for territory," he says.

"Moscow had sought to steadily destroy the moderate Syrian opposition on the battlefield, leaving only jihadist forces in play, and lock the US into a political framework of negotiations that would serve beyond the shelf-life of this administration.

"In both respects, it has been successful.

"Ultimately, the Russian goal is to lock in gains for Syria via ceasefires, while slow-rolling the negotiations to the point that true opposition to the Syrian regime expires on the battlefield, leaving no viable alternatives for the West in this conflict come 2017.

"Russia's intervention, seeks to minimise losses, relying largely on the ground power of other actors to do most of the fighting, with its officers embedded in order to glue the military effort together and coordinate air strikes."

Testing ground

The Syria operation has also provided an invaluable opportunity for Russian generals to try out their forces in operational conditions, as well as offering something of a "shop-window" for some of Russia's latest military technology.

Mr McDermott says: "The Russian General Staff see this as an opportunity to test new or modern systems; experiment with network-centric warfare capability; and to present evidence of the success of military modernisation."

The Russian air force has deployed some of its most modern aircraft to Syria, though the same cannot be said for the munitions they employ.

The Russian air campaign overall has relied upon the use of "dumb bombs" of various types, a major distinction with modern Western air campaigns, where almost all of the munitions used are precision-guided.

The Russian military has deployed many weapons systems to Syria

Russian special forces and artillery have been engaged on the ground.

Long-range missile strikes have been conducted from Russian warships and submarines.

Even Russia's only aircraft carrier is now on its way to the region.

Syria has become a kind of "sampler" of Russian military capabilities.

Diplomatic advantage

The diplomatic consequences of the Russian intervention have also been a plus for Moscow.

Its active military role in the region has reshaped its relationships with Israel, Iran and Turkey.

Indeed, Israel and Russia have developed a significant level of understanding.

Israeli air operations against the Lebanese Shia militant group Hezbollah, for example, have not been hindered by Russian control of significant parts of Syrian air space.

Relations between Moscow and Tehran (Syria's only other significant ally) have developed, and even the enmity between Moscow and Ankara has been diminished, with both countries realising they have to accommodate - at least to an extent - the other's regional aims.

Syria has seen the United States reassess its relationship with Moscow

But it is US-Russia relations that have been most profoundly influenced by Moscow's intervention in Syria.

At one level, Syria can be added to Ukraine as a dossier where the US and Russia are failing to find common ground.

But Russia's military role ensured that the Assad leadership was not going to be removed from the chessboard.

This made Washington revise its own approach and pursue what has largely proved an illusory effort, to develop some kind of partnership with Russia.

The United States was compelled not just to deal with Russia as a diplomatic equal but also to shift its own stance towards the Assad government to one - that for all the obfuscation - falls well short of its long-time insistence that President Assad had to go, as the essential pre-condition for any negotiated settlement.

The indiscriminate nature of the Russian and Syrian air campaigns - exemplified by the current struggle over Aleppo - has certainly not won Russia many friends in the West.

Russia has been accused by several governments of barbarity and potentially committing war crimes.

According to the UK-based monitoring group the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, almost 4,000 civilians have been killed in one year of Russian strikes.

But Western public opinion seems largely unmoved by the struggle; perhaps to an extent a reflection of war weariness in the wake of the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

And there has been a good level of confusion.

Russian information operations, which insist upon presenting their Syrian campaign as a struggle for civilisation against terrorism, may convince few but pro-Russian trolls.

President Putin addressed a concert held in the theatre in Palmyra

They do, though, further complicate a story that is already so complex that many in the West, sceptical about their own governments' records, seem unwilling to get excited about what Russia is up to.

The importance of information operations was most clearly illustrated by the extraordinary concert mounted in the ruins of Palmyra after its recapture from so-called Islamic State (IS) by Syrian forces.

This, though, may have been directed as much at public consumption in Russia as at audiences abroad.

Mr Kofman says: "The Kremlin has skilfully managed how the Russian public sees this intervention.

"Domestic politics constrains Russia just as much, if not more so, than the limitations of its military capabilities.

"Given the woeful state of the economy, Russian leaders have always been concerned that Syria would come to be viewed as an undue burden."

Mr Kofman interprets the Kremlin's decision in March to announce a significant reduction of its air power in Syria as an attempt "to cash-out the political gains at home and recast the war in the public's mind".

"Rather than a prolonged campaign, Russia's combat operations have become the new normal," he says.

There has been widespread international condemnation of alleged Russian involvement in strikes on rebel-held areas of Aleppo

Western expectations of political peril for President Putin have, so far, simply not been realised.

Mr Kofman says: "Those expecting Russian support behind Vladimir Putin to collapse, either over Ukraine, or Syria, or the economy, have thus far been proven wrong.

"The Kremlin is demonstrably more adept at securing public approval, or apathy, than commonly acknowledged in the West."

Russian casualties in Syria are difficult to estimate.

Helicopters have certainly been shot down, and several members of Russia's special forces are known to have been killed in combat.

But the overall level of casualties appears to have been limited, and news of combat deaths (like those among Russian forces in eastern Ukraine) is restricted - another reason why there has been no domestic backlash against the Syrian adventure.

Will Russia attempt to secure a political settlement for Syria at the conference table?

By its own standards, Russia's intervention in Syria has been a success on several levels.

The real question is whether this situation can last.

Put it another way, is there any clear exit strategy for Russia that might enable it to bank its gains and end its losses?

Mr McDermott says: Russia's strategic goals are vague.

"The exit strategy, if there is one appears rooted in strengthening the fighting power of the Syrian army and securing some long-term political settlement that demonstrates Russia has returned as a great power," he says.

Mr Kofman says the "strategic impact" of Russia's intervention still remains in doubt.

"Such gains are readily lost and can prove illusory," he says.

"The Syrian army remains a shambles, Iran is attached to Assad, while Russia is more interested in the grander game with the US.

"And without a political settlement to secure them, these accomplishments can vaporise, as Russian patience and resources become exhausted.

"Russian leadership knows that this could take years and would rather cut a deal while possessing the military advantage."