Aleppo: Is a no-fly zone the answer?

- Published

Amidst the growing revulsion at the bombardment of Aleppo by Syrian and Russian warplanes and with the number of civilian deaths rising, there is a clamour for something to be done.

Would it not be a good thing, many wonder, to take decisive action to try to end the carnage?

US Secretary of State John Kerry tried diplomatic means.

He wanted to ground Syrian and Russian warplanes by agreement or at least restrict Russian operations to those against so-called Islamic State (IS), and other extremist groups linked to al-Qaeda.

His efforts of course failed and the offensive against Aleppo was re-doubled in intensity.

If the US wants to change the military dynamics there are really only two broad ways of doing this.

Either it has to intervene directly itself - and there is little appetite for that.

Or it has to bolster its efforts to train, advise and equip friendly forces on the ground.

It has to step up what it is already doing; an approach that has proved problematic.

Direct intervention?

The US has struggled to find so-called moderate allies in Syria who have any capacity to make a difference on the battlefield.

Those that are capable - like the Kurds - bring additional problems due to their own regional ambitions.

Providing better weaponry to opposition groups is another option - man-portable surface to air missiles would clearly alter at least the Syrian Air Force's calculations - but these weapons could easily leak to extremist groups - the sort of "blow-back" that resulted from the initial arming of the Taliban in Afghanistan to fight the Russians.

Russian pilots could simply change their tactics to reduce any exposure to such weapons.

Remember too that despite its antipathy towards the Assad regime, Washington's main focus in the region is the battle against IS.

Russia carried out its first air strikes on 30 September 2015

So what about intervening directly?

One frequently touted idea is the imposition of a "no-fly zone" that would be monitored and patrolled by US and allied warplanes.

In pure logistical terms this would require tens of thousands of personnel and a variety of aircraft from air superiority fighters; to more tankers and more AWACS radar and control aircraft.

Without significant additional resources it would be a serious distraction from the on-going campaign against IS and Mosul in particular.

'Fundamental decision'

But while a no-fly zone sounds attractive as a proposition it has huge problems.

Those advocating such a zone should be under no illusions.

Last month in a Congressional hearing, General Joseph Dunford, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, was asked what he thought about the imposition of a no-fly zone to halt the barrel-bombing in Aleppo.

His response was clear. "Right now", said the highest ranking US serving officer, "for us to control all of the air space in Syria would require us to go to war against Syria and Russia; that's a pretty fundamental decision…"

Russia effectively controls Syrian air space, having deployed highly capable S-400 air defence missiles and radars at its Syrian base.

It has now brought in S-300 missiles, which have an additional capability against other missiles.

And Russian warships in the Mediterranean could add to the air defence shield. Enforcing a no-fly zone would require a willingness to down Russian and Syrian aircraft in a highly contested environment.

Typically any US operation to institute such a zone would require enemy air defences to be destroyed at the outset. A US strike against Russian SAMs (surface to air missiles) is surely unthinkable.

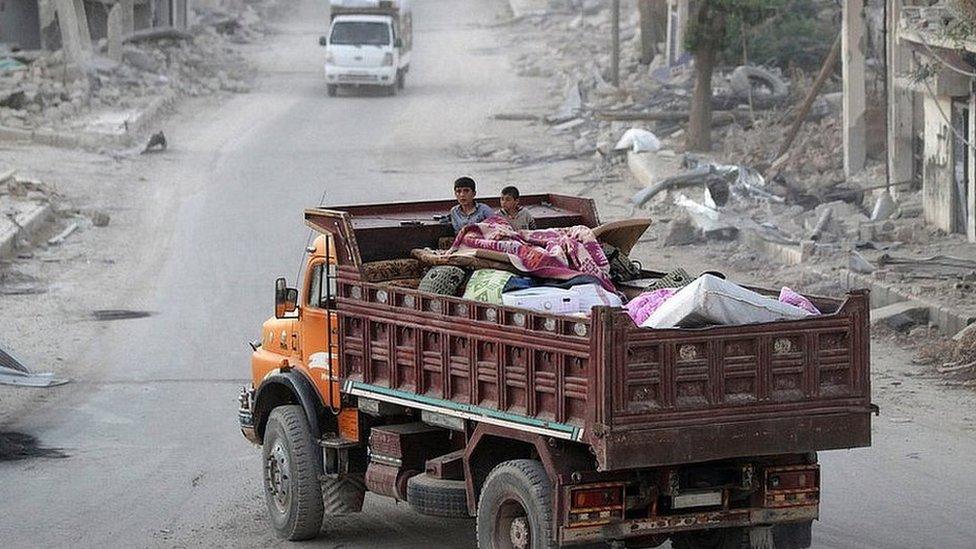

Aleppo has been under intense aerial bombardment

Perhaps, though, tough action could call Russia's bluff?

Russia did not respond in kind when Turkey shot down one of its planes over northern Syria.

But the Turks were defending their own air space, not enforcing a no-fly zone over Syria.

And the Russians are in a strong position.

Their air defences are in place and additional combat jets could be moved to Syria at short notice.

Russian spokesmen have warned the Americans off - making it clear that any attack even on Syrian government forces by the Americans will be viewed as an attack on Russia.

'No easy options'

So if a no-fly zone is so risky, are there any other options?

One, frequently discussed in Ankara, is the imposition of some kind of "safe zone" in Syria within which refugees could be protected.

This may be easier to achieve.

Turkish troops already occupy a zone inside Syria along their own border.

This clearly has air cover from Turkish warplanes and, vitally, Turkish troops on the ground.

Perhaps this could be an embryonic safe zone though this option too is not without problems and this particular zone would do nothing for Aleppo.

No-fly zones, by the way, are no panacea in themselves to end the bloodshed.

US warplanes enforcing such a zone over Iraq had to watch as Saddam Hussein's ground forces intensified their attacks on his opponents.

Artillery, mortar and tank fire can be just as damaging as bombing.

As ever in Syria, there are no easy options for the West.

The Democratic contender Hillary Clinton has in the past backed the idea of no-fly zones.

But with Russia firmly engaged alongside the Assad regime, any kind of direct US intervention would raise the stakes to a dramatic level.

- Published11 October 2016

- Published10 October 2016