Srebrenica survivors on Aleppo 'No lessons learned'

- Published

People in Sarajevo, itself besieged during the Bosnian War, gathered to protest at the bloodshed in Aleppo

Hasan Hasanovic was standing in front of his house in Srebrenica when he saw the Bosnian Serb soldiers coming in. The only way to survive was to run.

That was on 11 July 1995. Srebrenica had been declared a safe area for civilians by the United Nations two years earlier.

Bosnian Muslims from the surrounding area had sought refuge there as the Bosnian Serb army carried out a campaign of ethnic cleansing, expelling non-Serb populations.

Some 20,000 refugees had fled to Srebrenica, then under the protection of a Dutch contingent of UN peacekeepers. But Bosnian Serb forces led by commander Ratko Mladic besieged the town and, days earlier, started shelling it.

When Srebrenica fell on that summer day, Hasan was 19.

"We all thought the UN would protect us until the end of the war," he tells the BBC. "We were just waiting for the war to end, thinking that we were safe under the UN.

"I didn't have time to go back home and say goodbye. We knew that if we went to the UN base we wouldn't be protected, we knew they would hand us to the Bosnian Serbs and we would be killed."

Seeing the troops coming in, he said, thousands of refugees took to the streets in panic.

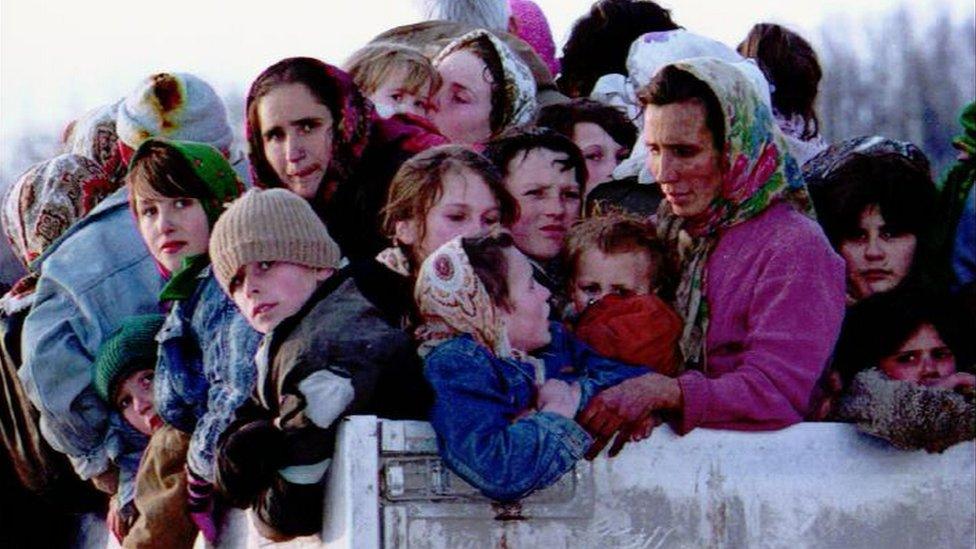

Women and children were evacuated from Srebrenica

With his twin brother, father and uncle, Hasan ran to the dense forest on the edge of the town and joined a column of some 12,000 men and boys, who also thought that the only option was to leave, marching to the nearest Muslim territory.

So, on that evening, they set off towards Tuzla, 55km (34 miles) away.

It was not going to be an easy journey. Their route included hills and rivers, and various attacks broke the group up into smaller parts.

In one of them, he lost sight of all his relatives. "Every day, the walk to Tuzla was a struggle for survival. I was constantly on the edge between life and death. I was being hunted like an animal," he says.

Thousands of Srebrenica residents sought refuge in nearby Tuzla

It took him six days before he reached safety in Tuzla, with just a fraction of those who had joined the march.

Only years later Hasan learned that his father, twin brother and uncle had died in the journey.

The relatives who had been left in Srebrenica survived by seeking refuge at a UN base in Potocari, and were reunited two weeks after he arrived in Tuzla.

What Hasan escaped in Srebrenica was the worst single atrocity in Europe since World War Two. In just a few days, some 8,000 men and boys were killed.

The question of what was not done by peacekeepers to protect those killed resonates to this day.

But while the circumstances in Aleppo differ from those in Srebrenica - not least in that there is no United Nations presence in the besieged districts - there is anger among Bosnian survivors that not enough has been done by international powers to protect civilians who are once again in the firing line.

Hasan's story: 'We don't have any excuses'

Hasan has since returned to Srebrenica. From there he watches a tragedy with, he thinks, many similarities unfold in the Syrian city of Aleppo.

There is growing concern over the fate of at least 50,000 civilians, according to UN estimates, who are besieged there by government forces and are under intense bombardment.

Rebels opposed to President Bashar al-Assad have held eastern parts of Aleppo since 2012. But a major government offensive, backed by Russian air power, has squeezed them into an area of some 2.5 sq km.

And as violence there intensifies, the UN says there is reliable evidence of summary executions of 82 civilians by pro-government forces - claims Syria's government has denied.

Mass graves later revealed the extent of the atrocities in Srebrenica

Russia vetoed a UN resolution last year that would have called the massacre at Srebrenica genocide

Inside Aleppo, residents say dead bodies lie on the streets as people are frightened of going out to move them. Food is scarce, they say, and there is no medical treatment for the injured. Many have grown so desperate that they have sent final goodbye messages on social media.

"The people in Aleppo feel the same way we did," Hasan says.

"We felt like being abandoned and not belonging to this humanity," he says. "Not being treated like a human. We keep repeating 'Never again' but when it comes to action, we don't do anything to prevent those things from happening.

"It seems the world hasn't learned anything. We are living in this modern world with technology and we don't have any excuses to say 'We didn't know'."

Nedzad's story: 'Let me send a message to the world'

Nedzad Avdic and his father also joined the column of men which left Srebrenica for Tuzla. He had moved to Srebrenica with his family in 1993 after their house in a nearby town was destroyed by Bosnian Serb forces.

When the city fell in 1995, he was 17.

The attacks on the group left him alone, lost in woods. Exhausted and starving, he and some 2,000 men and boys surrendered to the Serbs.

They were later taken to a field to be executed, he recalls. He was forced to take off his clothes, then one of the soldiers tied his hands behind his back. Around him, there were piles of dead bodies.

The men were lined up five by five just before the soldiers started shooting at them. He was injured in the stomach, right arm and left foot. As the people were hit, he said, their bodies were falling on the ground. He could hear their gasping last breaths.

The shooting continued until late in the evening. Only when the soldiers left did he raise his head and notice that there was another survivor, with minor injuries. They untied one another and managed to escape.

They sought refuge in the forest again and managed to reach safety eight days after leaving Srebrenica. Most of his male relatives, including his father, were killed.

What happened at Srebrenica? Explained in under two minutes

Now, Nedzad says, he recognises himself in the image of the children from Aleppo.

"They are hoping for someone to help, but their hope has been in vain," he says from Srebrenica, where he now lives.

"It's very possible that Aleppo will have the same destiny of Srebrenica. I survived genocide, so let me send a message to the world: 'Don't allow Aleppo to become a new Srebrenica'.

"I hope the world will finally do something. It's not enough to hear the words 'Never again'. It's a shame to allow this happen."

Emir's story: 'My suffering has been in vain'

Emir Suljagic was also 17 when he moved to Srebrenica in 1993 from Bratunac, a small town on the Bosnia-Serbia border where he lived with his family.

When the UN mission arrived, he secured a job as translator, working with the observers. And that was what saved his life, he says.

Only his mother and sister also survived - they had left for Tuzla in April 1993. His 70-year-old grandfather was one of the thousands killed when Srebrenica fell.

"The feeling you have is of complete powerlessness, that someone else is holding your life in their hands," says Emir, who is the author of Postcards from the Grave, a first-hand account of the massacre there.

"Aleppo is the end of the notion that the international community stands for values. My suffering has been completely in vain. Bosnia got butchered, Bosnia got raped."

Years of fighting have left parts of Aleppo destroyed

"Look at Aleppo and Syria and tell me what's different. Nothing," he adds.

He fears the killings will not end in Aleppo - but may spread to the city where many Aleppo refugees have fled.

"I'm not surprised. I have no illusions. It's Aleppo today, it may very well be Idlib tomorrow.

"The lessons that we are not learning will keep coming back to haunt us."

- Published28 November 2022

- Published18 March 2016