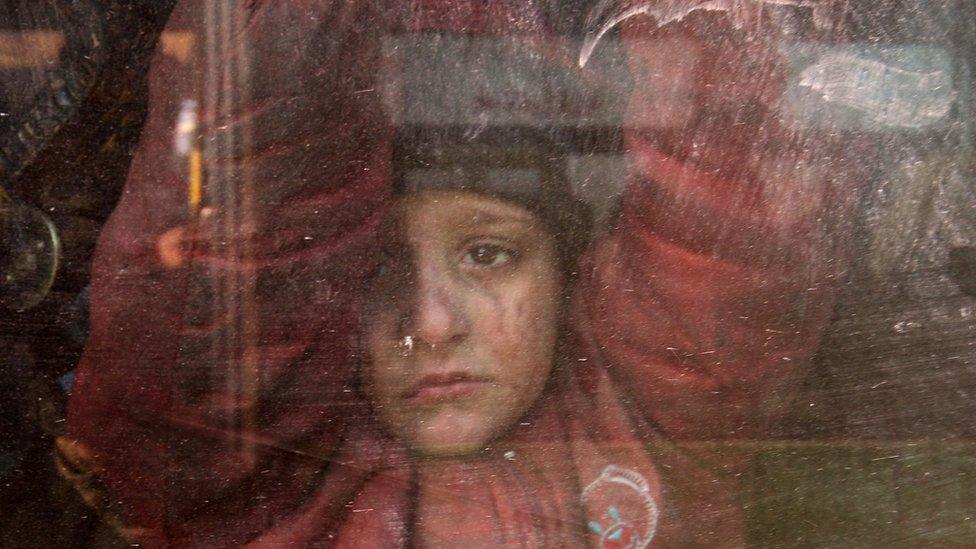

Aleppo's evacuated children 'traumatised, hungry and dirty'

- Published

The children are traumatised after months of bombing

Children have been arriving in rebel-held territory in their hundreds, the survivors of a brutal bombing campaign which has reduced eastern Aleppo to rubble.

They had been trapped between pro-government forces and Russian fighter jets on the one hand, and the remaining rebels on the other.

Packed onto the buses, they were hungry, tired and - above all - traumatised.

But for those waiting to treat them as they reached the countryside, it was the look on their faces which was most striking.

"Some of them look at people as if they are from another planet," said Dr Ghanem Tayara, of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organisations (UOSSM).

"There are people who have had nothing for three days, children who are wetting themselves constantly, who keep starting to show some hysterical reaction, as if the bombs are going to fall still."

Hundreds of children arrived in rebel-held territory on buses on Monday alone

Many of the children hadn't showered "for one-and-a-half to three months", and then - a final indignity - were forced to soil themselves on the buses carrying them away from their home, Dr Tayara claimed.

"During the evacuation process, they were held on buses for 14 hours. About 90% of them who arrived were all wet."

It was people like Dr Tayara's colleagues who were on the frontline when the refugees began to pour into the rebel-held rural areas to the west of Aleppo last week.

Along with other aid agencies, they are now faced with putting back together children who may not only be physically injured, malnourished and dehydrated, but who are also carrying the scars of living in a warzone.

It is going to be a long process.

It is not known how many children may still be in east Aleppo

"They will need immediate care, medium and long-term care," said Shushan Mebrahtu, of Unicef Syria, which is working with partner agencies to put in place a plan. "Of course, they need medical care, psychological counselling. They are in need of warm clothing.

"Going forward, they really need to get back to a kind of stability - their childhoods, their education."

Some of those things can be provided quickly by the teams waiting to greet them as they cross from government-held areas into rebel territory.

"We care about these children - now they have some food and clothes and other things," said Mustafa Ozbek, of IHH Humanitarian Relief Foundation. "There is no bombing, which is good for the children.

"They are more happy now, I think, but when you see the pictures, they are not happy. They left their homes - it is a bad situation."

Evacuees from rebel-held eastern Aleppo have been receiving aid in a neighbourhood in the west of the city

The sheer numbers can seem overwhelming - 2,700 had arrived in the convoys by Friday. Dr Tayara estimated another 250 to 300 arrived on Monday, 47 of them orphans who had appeared in a video begging for help just days before.

But these children are just a handful of the millions who have had their lives overturned by the five-year civil war, Ms Mebrahtu pointed out.

"Many more children in Syria are also going through things no child should endure, no adult should endure," she said. "This conflict has to end - the life of many more children depends on it."

Even those who have escaped the bombs falling on eastern Aleppo face an uncertain future.

"Is there hope?" Dr Tayara mused. "It is a tricky question. Either die there or be evacuated, and become refugees for the rest of their lives.

"They don't have much choice."