Israel and the Palestinians: What are alternatives to a two-state solution?

- Published

Donald Trump's remarks broke with decades of US policy

When President Donald Trump commented "two states and one state - I like the one that both parties like" about an eventual Israeli-Palestinian settlement, it suggested a rethink, and perhaps a downgrading, of the time-honoured "two-state solution" of past US administrations.

But what are the other options?

Origin of partition

To understand where the concept of sharing or dividing this piece of land comes from, it is important to look at its recent past.

Arab nationalism and Jewish nationalism arose during the same period of history with claims to the same territory. This rationale was the underlying basis for an equitable solution, based on partition and a two-state solution.

In 1921, TransJordan (now the state of Jordan) was formally separated from Palestine (now Israel and the West Bank/Gaza). A UN resolution in 1947 proposed a second partition, this time of the territory west of the river Jordan.

One part would be a state where Zionist Jews constituted a majority, the other where the Palestinian Arabs would be a majority of the population, but the latter rejected the idea.

Competing claims

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Jordan occupied the West Bank. Egypt in turn controlled Gaza.

During the Six Day War in 1967, Israel defeated Jordanian forces and conquered the West Bank. Similarly Egypt was forced to leave the Gaza Strip.

While the Israeli Left was willing to return territory to Jordan for regional peace, the rise of Palestinian nationalism under Yasser Arafat and the ascendency of the Israeli Right under Menahem Begin initially proposed polarised solutions - either a Greater Israel or a Greater Palestine, but not a two-state solution.

The Israeli Right argued that there were nationalist and religious reasons for retaining the West Bank. Some on the Israeli Left wanted to build socialism on the West Bank through the construction of a network of kibbutzim.

Israeli security experts, meanwhile, believed that the West Bank provided strategic depth to slow down an invading army. All this led to a burgeoning settler movement.

Two states

Yasser Arafat started to move towards a two-state solution after 1974 (though some saw this as a ploy) and established a Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Gaza, following the Oslo Accords with Israel in 1993.

Successive Israeli prime ministers - Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu - have all accepted the idea of a Palestinian state, but have differed in terms of what it should actually comprise.

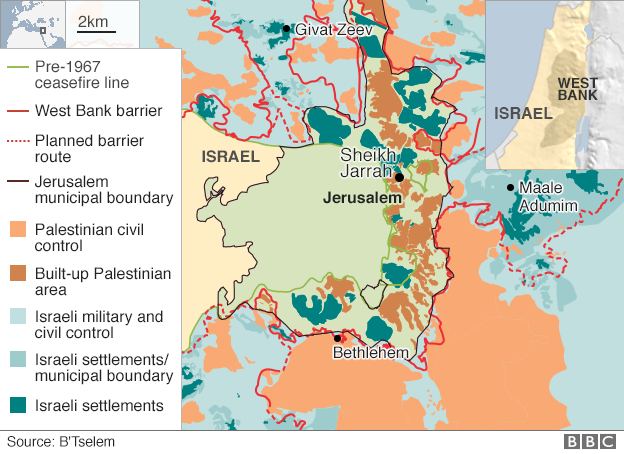

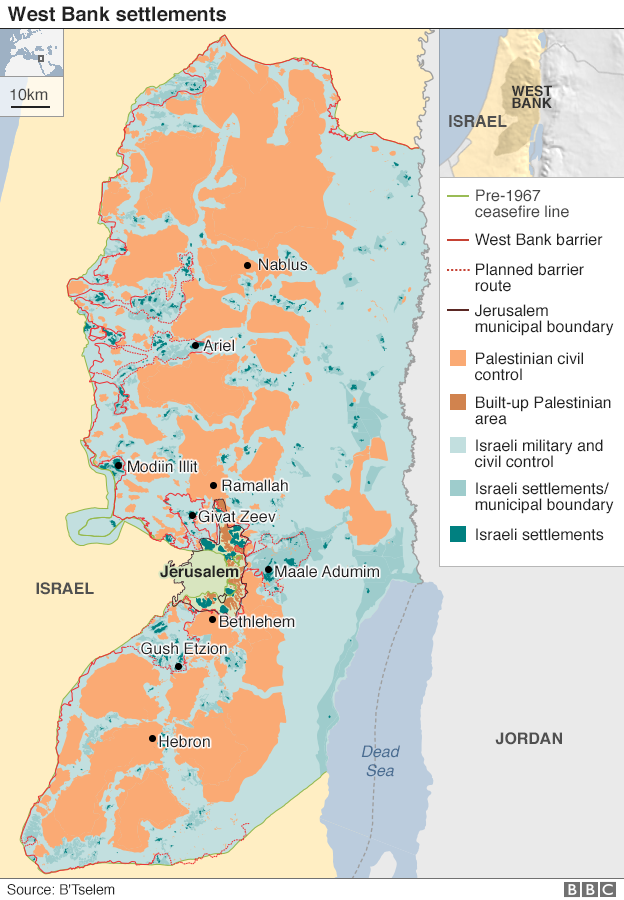

Recent advocates of the two-state solution have suggested an Israeli border near the West Bank barrier, which would encompass a majority of Israeli settlers. This may well be the basis for a plan eventually put forward by the Trump administration.

Despite proclamations of a State of Palestine by Arafat and his successor, Mahmoud Abbas, it has never materialised as a de facto entity, and despite Mr Netanyahu's declaration of support for a Palestinian state in 2009, it is unlikely that any right-wing government would permit its emergence for both ideological and security reasons.

The takeover of Gaza in 2007 by Hamas produced a divided Palestinian Authority. The nationalists controlled the West Bank while the Islamists ruled Gaza.

Yasser Arafat achieved self-rule for Palestinians but no state

In the past decade any reconciliation has been based more on public relations than on public reality. This has led to the idea of two Palestinian states or autonomous areas for the Palestinians.

One fundamental difference between the two sides has been support for a two-state solution by Palestinian nationalists, but no unambiguous statement to this effect from Palestinian Islamists.

Their objection is essentially theological in that the entire territory from the Mediterranean to the River Jordan should be under Islamic rule with no land being ceded.

One state

A one-state solution is based on the premise that it is highly unlikely that today's 400,000 Jewish settlers in the West Bank will leave voluntarily or be evacuated forcibly.

Those on the Israeli far-left regard such a unitary state as being a state of all its citizens.

However critics on the Israeli side point out that within a few years the number of Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank and Gaza and the number of Arab citizens of Israel itself will have reached parity with the number of Jews in Israel and in the West Bank.

Decades of on-off peace talks have failed to reach a final settlement

Given that the Arab birth-rate is higher than the Jewish one, if voters vote according to their ethnic origin, then this means the end of Jewish self-determination in their own nation state.

Some on the Israeli far-right favour either a full or partial annexation of the West Bank while restricting democratic rights for the Palestinians.

Meanwhile, an interim solution of a bi-national state would see both national groups working constructively within the same state, but one which offers protection for their political and legal rights and preserves their national identity.

Nationalism however has proved to be a powerful force in recent times with the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia into individual nation-states - and some have argued that while a one-state solution is logical in a theoretical sense, the national enmity between Israelis and Palestinians would produce an unworkable entity.

Three-state confederation

The idea of a confederation between Israel, Palestine (West Bank/Gaza) and Jordan has been debated ever since 1948.

A former Israeli foreign minister, Abba Eban, vigorously promoted a Benelux-style economic union solution. The Israeli Labour government after the Six Day War adopted variations of a solution known as the Allon Plan, which effectively partitioned the West Bank between Israel and Jordan with remaining territory under local Palestinian autonomy.

However, it was the rise of a Palestinian national identity in the 1970s which scuppered this idea in favour of a Palestinian state. Ever since, both Jordan and Egypt have shown little enthusiasm for reassuming responsibility for the West Bank and Gaza.

Autonomy

Former Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin proposed the idea of administrative autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza shortly after coming to power in 1977.

Self-rule for the Palestinians meant that Israel would be responsible for security and foreign policy while ideologically retaining a claim to Judea and Samaria (West Bank).

While limited autonomy was granted under the Oslo peace accords, it was probably viewed by both sides as an interim solution. The demise of the peace process has frozen any further progress.

The eventual shape of a final settlement has therefore yet to be determined.

Colin Shindler is emeritus professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. The author of numerous books on Israel, his The Rise of the Israel Right (Cambridge University Press) was awarded the gold medal in The Washington Institute for Near East Policy's 2016 Book Prize competition.