Yemen conflict: How my country has changed

- Published

Before the war: Mai (left) and her sister look out across the Sanaa skyline in 2009

It is two years since the start of the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen in support of the government ousted by Houthi rebels. In that time, thousands of civilians have been killed, parts of the country devastated and Yemen left teetering on the brink of famine.

Here the BBC's Yemen-born Mai Noman, who has returned to her homeland to film short documentaries, reflects on what has become of her country.

It's been over two years since I was last here. The only place I call home.

A lot has happened and much has changed. It's hard to keep my feelings in check.

Beside the physical destruction, memories of what once was are buried under the heavy weight of emotional rubble.

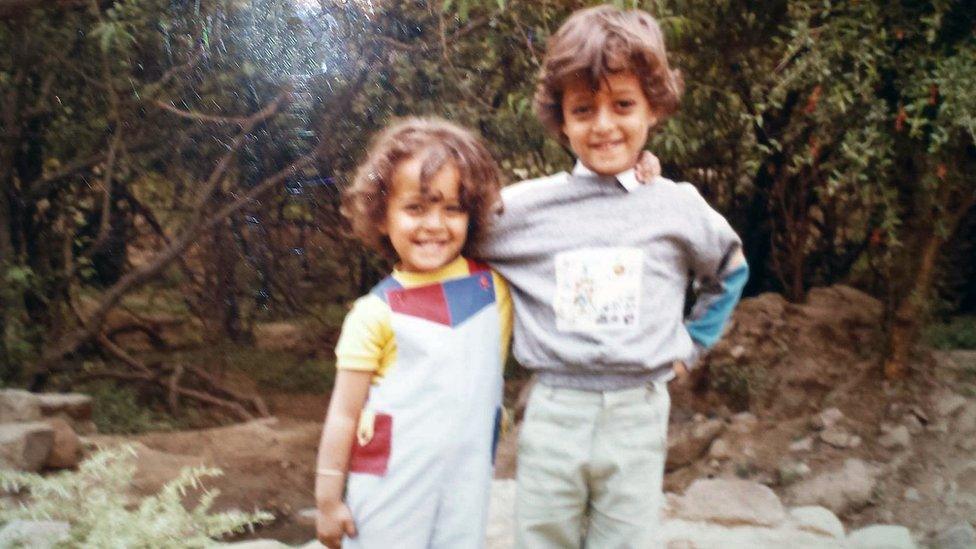

Mai and her brother grew up in Taiz

As a Yemeni journalist working in international news, I have had to monitor every twist and turn of the civil war in my country, even when I wanted to look away.

Truthfully, the thought of coming face-to-face with the new reality shaped by the furious conflict in Yemen has terrified me.

But living through the war from outside Yemen was isolating.

As we make our way to the capital, Sanaa, on a rugged 10-hour car journey from Aden, I think back to the number of times I quietly broke down after hearing news coming out of Yemen. Working in a newsroom, this happened often.

This trip takes me from the south to the north - two parts of a country divided by more than mere miles.

In simple terms, the south is under government control, backed by the Saudi-led coalition, and the north is controlled by the Houthi rebels. But the reality is more complicated.

Same city

I've imagined arriving back home hundreds of times in the last few years. But on the day I was totally unprepared for what I found.

Unlike the southern city of Aden, where life seems to be at a standstill, waiting in fearful anticipation of more fighting, Sanaa - apart from the obvious damage - appears the same as ever.

Some beautiful buildings in Sanaa have escaped unscathed

I can feel the rain approaching. After London that should make me shudder, but it somehow feels welcoming.

The jagged mountains which encompass the city slowly fill with clouds transforming the sky into a splendid portrait of misted rocky peaks. All at once telling me I'm home.

The Yemeni capital has suffered like other parts of the country, but life there goes on

There are more restaurants in town than I recall, and many are over-flowing with people.

For a moment I forget there's a war raging across the country. But then Sanaa can be deceptive.

I feel exhausted by the time we arrive at my cousin Mona's house.

I knock on the door in a typical Yemeni manner - very determinedly. Mona's youngest child, Abdullah, opens the door to greet me.

Mai's aunt's car sits where it was hit by a falling missile in the garden of her home

It's quite quiet here. A minute later I hear Mona making her way down the narrow stairs at the back of the house.

We embrace with joy. She holds my face to see what's changed.

"You're still you," she says. A lot kinder than comments I receive later about how my hair is too short or the few extra pounds I've gained.

No answers

Mona is just as beautiful but her voice has changed, she's gone through a lot in the last few years.

Three years ago she lost her father suddenly. She had been very close to him and facing life without him, amid ongoing uncertainty, is hard.

"He was the biggest support I had," she tells me, breaking down in tears.

Life hasn't been kind to her and the war has now brought with it seemingly endless questions.

Would her family be able to leave if it had to? Is it better to be stuck inside surrounded by conflict, or outside separated from relatives and friends? Are Mona's children safe at school or sleeping in their beds? How many more funerals will she have to attend?

I have no answers.

Even with the most difficult issues I face in my own life, the choices are never so bleak.

Our lives have become more different than ever.

Over the course of three weeks in Yemen, I reconnect with old acquaintances and hear stories of separation, loss and incredible examples of the tight bonds that keep a community together.

But something else weighs heavily on my heart. There is one place I wasn't able to visit.

Ruined lives

It's the place where I was born and where a more utopian notion of Yemen was engraved in my mind.

My grandmother's house in Taiz.

But sadly my grandmother is no longer with us and Taiz today is unrecognisable, sitting as it does on the frontline of the conflict. I wonder if I'd even know the house.

The fighting on the ground is brutal, the bombardment by the Saudi-led coalition is relentless and the siege on the city by the Houthis continues.

It's painful trying to accept the way things have become, one where precious memories have no place among the hardship of this grinding conflict.

To me, Taiz is where the heart of home is, and there's nothing harder than losing one's home.

When I set off for Yemen it was with a mixture of dread and trepidation at what I might find after years of bombardment and fighting.

On arriving I fell into a false sense of relief that the people were still here; home was, in some form, still here.

In the days which followed though, it became clear that war damage isn't just the craters and the bombed out buildings.

It is the suffering of a population watching helplessly as their lives are being torn apart.

Thinking of the time I spent fearing what I'd find when I returned home, I know that regardless of the pain of seeing my country at war, the sense of longing to be part of Yemen, for good or bad, will always draw me back.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published14 April 2023