Syria government 'producing chemical weapons at research facilities'

- Published

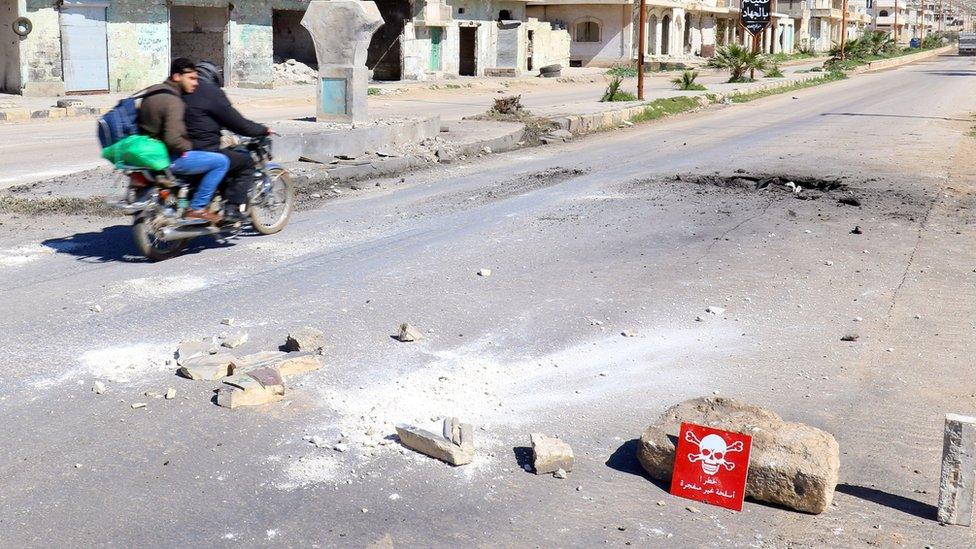

Abo Rabeea says he is still suffering from the suspected chemical weapons strike in Khan Sheikhoun

Syria's government is continuing to make chemical weapons in violation of a 2013 deal to eliminate them, a Western intelligence agency has told the BBC.

A document says chemical and biological munitions are produced at three main sites near Damascus and Hama.

It alleges that both Iran and Russia, the government's allies, are aware.

Western powers say a Syrian warplane dropped bombs containing the nerve agent Sarin on an opposition-held town a month ago, killing almost 90 people.

The United States launched a missile strike on a Syrian airbase in response to the incident at Khan Sheikhoun, which President Bashar al-Assad says was faked.

The intelligence document obtained by the BBC says Syria's chemical weapons are manufactured at three sites - Masyaf, in Hama province, and at Dummar and Barzeh, both just outside Damascus. All three are branches of the Scientific Studies and Research Centre (SSRC), a government agency, it adds.

Despite monitoring of the sites by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the document alleges that manufacturing and maintenance continues in closed sections.

It says the Masyaf and Barzeh facilities both specialise in installing chemical weapons on long-range missiles and artillery.

The OPCW mentioned Barzeh and Dummar - also known as Jamraya - in its latest official progress update, external on its work to eliminate Syria's chemical weapons programme.

The watchdog says inspectors visited them between 26 February and 5 March and that it is still awaiting laboratory analysis of the samples that were taken.

Read more

The US imposed economic sanctions on 271 SSRC employees three weeks after the Khan Sheikhoun incident, accusing, external the agency of focusing on the development of non-conventional weapons and the means to deliver them.

It is promoted as a civilian research institute by the Assad government.

A source familiar with weapons inspection protocols says it is plausible that a government might only declare certain facilities on any given site to the OPCW and therefore only give inspectors access to those areas.

The intelligence document also accuses Syria of falsely declaring the work of one of its research branches as defensive - when it really continues to develop offensive capabilities.

In addition, it names senior official Basam Hassan as a key figure in authorising the use of chemical weapons.

He was previously described on a 2014 US sanctions list, external as President Assad's representative to the SSRC, with the rank of brigadier-general.

OPCW inspectors recently visited two of the SSRC facilities named in the intelligence report

In a statement emailed to the BBC, the OPCW said it had asked the Syrian authorities to "declare the relevant parts" of the SSRC sites, as per their obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), an international treaty prohibiting their use.

Although the authorities have declared sections of those sites, the statement said that was "not yet sufficient".

The watchdog said it was "not yet in a position to confirm that the [Syrian] declaration is complete and accurate"

Countries signed up to the CWC would soon get a report on the recent inspections, the statement added.

The GEKA facility in Germany was among those used to destroy Syria's chemical munitions

Syria was obliged to give up its stockpile of chemical weapons following an agreement brokered by the US and Russia in 2013, when Mr Assad signed up to the CWC.

The deal was agreed in the aftermath of a chemical attack that killed hundreds of people in opposition-held areas in the Ghouta agricultural belt around Damascus.

The United Nations said Sarin had been used in that incident - the same nerve agent the OPCW, the French government and others say was used in Khan Sheikhoun.

At least 87 people were killed in Khan Sheikhoun, according to the UK-based monitoring group, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

The OPCW says victims were exposed to Sarin or a Sarin-like substance in Khan Sheikhoun

Video posted in the hours following the alleged air strike showed people struggling to breathe and foaming at the mouth - some of the classic symptoms of poisoning by Sarin and other nerve agents.

The pressure group Human Rights Watch released a report, external on Monday alleging that Khan Sheikhoun was part of a wider pattern of chemical weapon use by Syrian government forces, including three other attacks involving nerve agents since December.

US President Donald Trump cited the pictures of children in distress as one of the reasons he decided to reverse previous policy on Syria and launch a cruise missile strike.

The missiles struck an airbase at Shayrat, which the US says was the place from which the chemical attack was launched.

French intelligence says Syria's government made the Sarin used in Khan Sheikhoun

The intelligence information about the suspected weapons manufacturing sites was shared with the BBC on condition the agency providing it would not be named.

It does not give detail about how the alleged evidence was gathered.

The Syrian government has denied using chemical weapons, with President Assad saying the accusations against his forces on 4 April were "100% fabrication".

In an interview last month with AFP news agency, he maintained that the entire arsenal had been dispensed with under the terms of the 2013 deal.

Bashar al-Assad, speaking in an interview approved by the Syrian presidency: "A 100%... fabrication."

"There was no order to make any attack, we don't have any chemical weapons, we gave up our arsenal a few years ago," he said. "Even if we have them, we wouldn't use them, and we have never used our chemical arsenal in our history."

The Russian defence ministry meanwhile says deadly chemicals were released in Khan Sheikhoun when a militant warehouse containing chemical munitions was hit in a government air strike.

The area is controlled by groups including Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which incorporates fighters formerly affiliated to al-Qaeda.

Both Russia and Iran have called for a "thorough and unbiased" investigation into what happened at Khan Sheikhoun, and insisted that only rebel and jihadist groups in Syria have access to chemical weapons.