Iran's Instagram election sees rivals battle on social media

- Published

The Iranian authorities have relaxed rules on internet use during the election campaign

This is an Iranian election like no other, where the main battles are being fought on social media.

For the first time candidates, as well as voters, have discovered the power of messaging apps as a way of bypassing state media and reaching out directly to each other.

Rather than relying on state television channels to broadcast their campaign rallies, the two front-runners - President Hassan Rouhani and his hard line rival Ebrahim Raisi - have been live-streaming them on Instagram.

At the touch of a button, anyone with a mobile device has been able to tune in, watch and show their support by adding to the blizzard of likes, hearts and smiley faces streaming across the screen.

They have also provided constant updates on Telegram, a hugely popular secure messaging app which now has more than 20 million users in Iran.

Former President Mohammad Khatami has publicly backed Hassan Rouhani

On Sunday, the reformist former President, Mohammad Khatami, posted a video message on Telegram urging voters to support Mr Rouhani, who is seeking a second term.

Mr Khatami is banned from appearing on state media and the main TV channels do not even show his photograph or mention his name. But his video went viral, reaching millions of Iranians connected via a vast network of Telegram channels.

In parallel to the presidential poll, local elections are also taking place across the country on Friday.

Read more

In the capital, Tehran, voters used Twitter and Telegram to challenge the official list of reformist candidates.

They began circulating an alternative list of progressive candidates they said had been forced off the reformist ticket.

The list caused such a huge stir on social media and prompted some very serious conversations in the reformist camp.

President Rouhani is live-streaming his campaign speeches

Unusually in a country where access to many websites and social media platforms is blocked, Telegram and Instagram are freely accessible in Iran.

When Telegram first appeared in Iran it was seen as a chat application with limited functionalities.

The establishment saw it as a relatively safe platform, and it was only when its Russian developers introduced new channel features, and Farsi-speakers began using it in a very different way, that its potential to mobilise millions of people became apparent.

Iranians have now created thousands of Telegram channels, and use "supergroups" not only to promote their agenda but also to do business and make money.

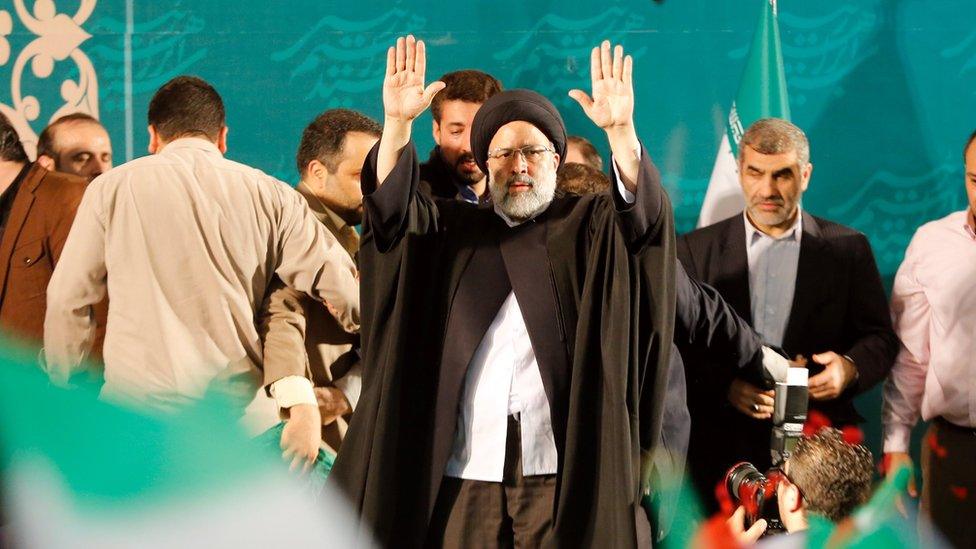

Ebrahim Raisi's supporters are also taking to social media

Telegram is suddenly being taken very seriously by the establishment and in the run up to the election the administrators of some popular channels have been detained.

Twitter is officially blocked in Iran but people use proxies to tweet.

President Rouhani and many of his cabinet members have been active on Twitter for the past four years; Mr Raisi hurriedly set up an account just before launching his campaign.

Usually, Twitter conversations that create a buzz then travel to Telegram channels where they can potentially reach a much wider audience. One such conversation discussed demands for gender equality and equal rights for women.

Mr Rouhani's campaign team has paid close attention to these conversations and identified keywords to include in his speeches about women, youth and internet freedom.

Mr Raisi, a hardliner, is backed by Iran's clerical and security establishment

In Iran, where free public debate is restricted and access to the media is controlled very closely, election campaigns are a rare opportunity for people from many different walks of life to make their grievances heard.

When Mr Rouhani's speeches have been streamed live on Instagram, for example, members of the LGBT community have taken the opportunity to post questions asking him directly about his views on gay marriage.

It would be unthinkable to ask such questions face-to-face in a public forum.

The president did not respond to the questions about gay marriage, but he has discussed other taboo issues during the campaign.

Mr Rouhani has not responded to questions about his views on gay marriage

Many people were surprised when the president attacked Mr Raisi over the former judge's role in the mass executions of thousands of dissidents in prison at the end of the 1980s.

It is a dark chapter in recent Iranian history, and one that is usually never mentioned. However, Mr Rouhani's comments prompted a sudden outpouring of heartfelt debate on social media.

The president also used social media to raise another unmentionable subject - corruption in the Revolutionary Guards. His veiled comments on the issue sparked off a debate online that soon moved offline into the world of everyday conversation.

For both voters and candidates, social media has also provided a way to bypass state censorship.

Mr Rouhani may be the president, but that did not stop state television from cutting parts of his campaign video before it was aired.

When the censors chopped out clips showing his supporters chanting the names of detained opposition leaders, Mr Rouhani's team released them on social media, allowing them to be watched by millions.

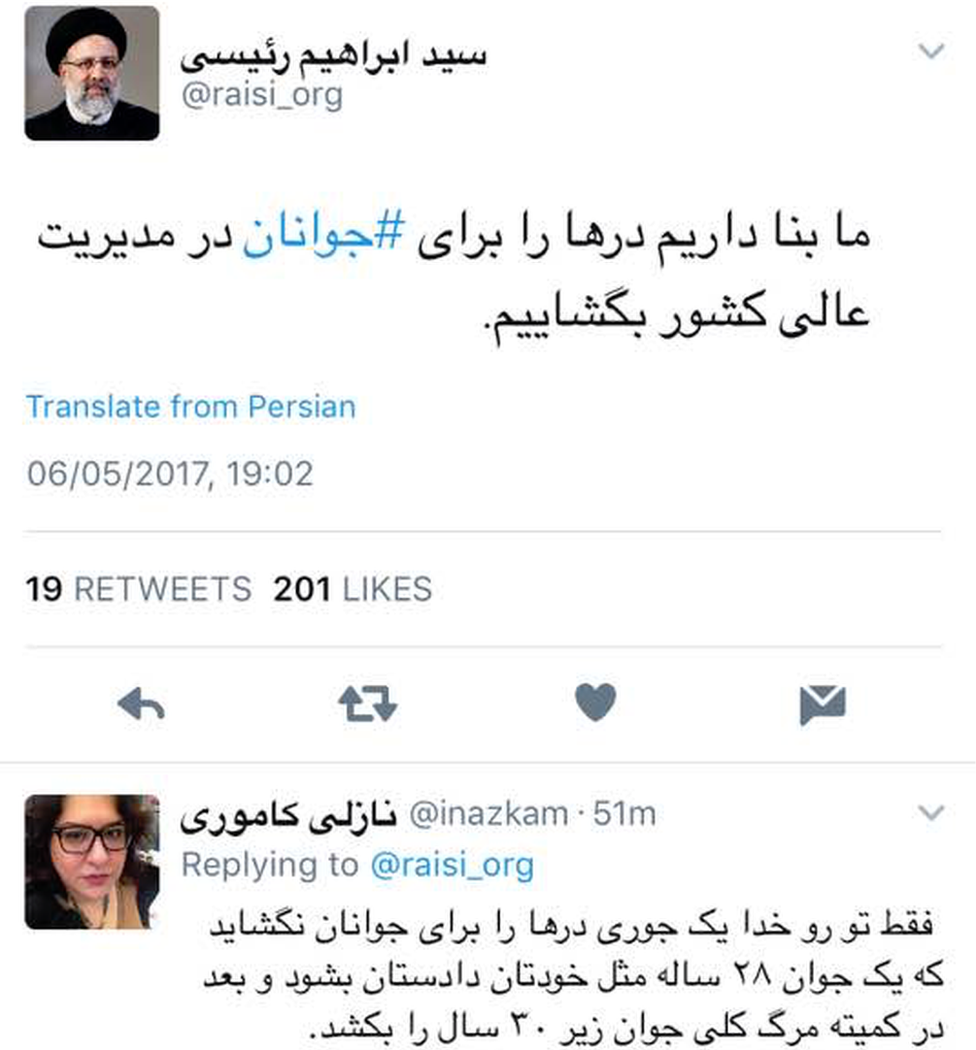

Ebrahim Raisi tweeted: “We intend to open to the youth the gates of senior posts in government.” In response, a woman wrote: “For God's sake, make sure you don't open the gates to 28-year-old prosecutors (like yourself) who would kill other 30 year olds.”

Mr Raisi now has an active fan base on Twitter. His hard line supporters steer conversations against Mr Rouhani and get involved in debates in support of their candidate.

But the president's fans have been fighting back, and Mr Raisi's Twitter account has been trolled by people opposed to his candidacy.

Throughout his campaign, Mr Rouhani has presented himself as an advocate for social media, reminding supporters that he has fought hard to ensure Telegram and Instagram remain unfiltered.

However, the role social media has played in mobilising people during this campaign has not gone unnoticed.

Instagram live-streams and Telegram supergroups are clearly a powerful weapon.

Whether access will still be available to Iranians after this election could depend very much on the outcome.

- Published16 May 2017

- Published28 April 2017

- Published12 April 2017

- Published4 June 2013